Diagnosis and Treatment of Gambling Addiction

CATR: How do we know when gambling becomes disordered?

Dr. Fong: Gambling crosses into disordered territory when it results in harmful consequences. It’s not about how often you gamble, or even how much money you’ve lost; it’s more about the role that gambling has in your life. If you continue to gamble in a way that’s harmful and distressing and emotionally painful, that’s an addiction. People with gambling disorder will continue to gamble despite these consequences, and they’ll experience urges and cravings to gamble that interfere with and impair daily life.

CATR: That sounds a lot like a substance use disorder (SUD).

Dr. Fong: Historically, gambling disorder has been placed in many categories: “process addiction,” “behavioral addiction,” and there was once a proposal for “hedonistic dysregulation syndrome,” which probably never caught on because it’s such a mouthful. But you’re right to point out the similarity to SUDs, because gambling disorder is an addictive disorder, just one that does not involve the ingestion of a substance. In fact, the DSM-5 moved gambling disorder from the impulse control disorders section into the substance-related and addictive disorders section. So according to the DSM, at least as of 2013, gambling disorder is an addiction. That said, the science is always evolving, and emerging technologies are making the distinction between various behavioral dysregulation disorders very fuzzy. We’re now seeing crossover with video games, internet gaming disorder, social media consumption, and gambling disorder. Someone may watch others play online video games excessively; maybe they don’t spend their own money, but they’re watching a slot machine simulator. Is that a gambling disorder? A gaming disorder? A social media use disorder? You can see how making these diagnostic distinctions gets messy, and it’s unclear how important those distinctions are clinically.

CATR: How common is gambling disorder?

Dr. Fong: Lifetime prevalence of gambling disorder hovers around 1% to 2% of the general population. And there is significant geographic variability. For example, 12-month prevalence can be as high as 3%–6% in some areas or as low as 0.1%–1% in others (Abbott MW, Public Health 2020;184:41–45). The prevalence is similar to bipolar disorder (BD) or schizophrenia. That’s a lot more common than most people realize. Why? Because people rarely like to talk about it. Has a patient ever come to your office with the chief complaint “I gamble excessively and I need help to stop”? Probably not. And I think that’s because of how we view money as a society. It goes all the way back to the morals and principles that this country was founded on. Back then, gambling was viewed as a vice and a sin but also as a way of escalating your future fortunes. So, these perceptions run very deep. People with money are seen as successful. And if you lose money, you’re not only a loser financially, but maybe character-wise too.

CATR: What are some important risk factors for gambling disorder?

Dr. Fong: The risk factors are like those we see for SUDs. Breaking it down along the lines of the biopsychosocial model is not only useful conceptually but can help create a treatment roadmap for individual patients. Look at their risk factors and use those to identify fruitful areas to intervene. There are genetic risk factors (Slutske WS. Genetic and environmental contributions to risk for disordered gambling. In: A. Heinz et al, eds. Gambling Disorder. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2019). Head injury is a potential risk factor. So is taking certain medications, particularly dopamine agonists (such as pramipexole and ropinirole) or partial dopamine agonists (such as aripiprazole). Many psychiatric conditions are associated with gambling disorder—particularly depression, BD, ADHD, SUDs, and antisocial personality disorder. Interestingly, even dementia is associated with gambling disorder. It may seem surprising at first, but it makes sense when you think of some of the psychological factors that drive the disorder, namely impulsivity and impairments in attention, focus, and cognition (Moreira D et al, J Gambling Studies 2023;39(2):483–511). The gambling industry are aware of this; we’ve all seen those buses bringing in older adults, many of whom are probably cognitively impaired.

CATR: Are there other psychological traits associated with gambling disorder?

Dr. Fong: People who develop gambling disorder are more likely to engage in high-risk and sensation-seeking behaviors and are very competitive (Rogier G et al, Scand J Psychol 2020;61(2):262–270). Also, and this may seem counterintuitive, people who don’t do well with loss—there’s higher risk in those with lower degrees of grit and resilience. I don’t have a good psychological term for this, but it’s captured in pop culture these days with the term “FOMO,” or “fear of missing out.” Many people with gambling disorder have an intense aversion to missing out on opportunities, in this case, to win money. It’s this aversion that drives ongoing gambling, even when it’s causing problems.

CATR: We covered bio- and psycho-; what about social?

Dr. Fong: This has to do with availability, access, and who is gambling around you. Is gambling prevalent in your community? Do your friends gamble? We’ve done work examining elevated levels of gambling in Asian American communities because the social entertainment of gambling is woven into the fabric of their society (Alegria AA et al, CNS Spectr 2009;14(3):132–142). For example, there is at least anecdotal evidence that casinos market more to certain Asian American communities, raising participation rates and social acceptance of gambling as a community activity (Keovisai M and Kim W, J Gambl Stud 2019;35(4):1317–1330).

CATR: Let’s talk about patient assessment. Do you think all patients should be screened?

Dr. Fong: Absolutely, and usually it isn’t done. We learn very little about gambling disorder and other behavioral addictions in training, so the topic usually goes unaddressed. It’s a silent addiction that’s easy to miss: Patients look fine, they can walk and talk, their balance is good, and they’re not overdosing. They’re distressed, but often you can’t see that, so it’s easy to forget if you’re not thinking about it. I tell my students that gambling disorder has never been listed as a cause of death on a death certificate, but many people have died because of the consequences of gambling disorder. Suicide rates are high; co-occurring psychiatric disorders are common. So, at the very least, we should be screening at intake. But the topic also should be revisited from time to time—I’d suggest annually. And keep it on your differential when a patient is not responding to standard treatments.

CATR: How should we go about screening?

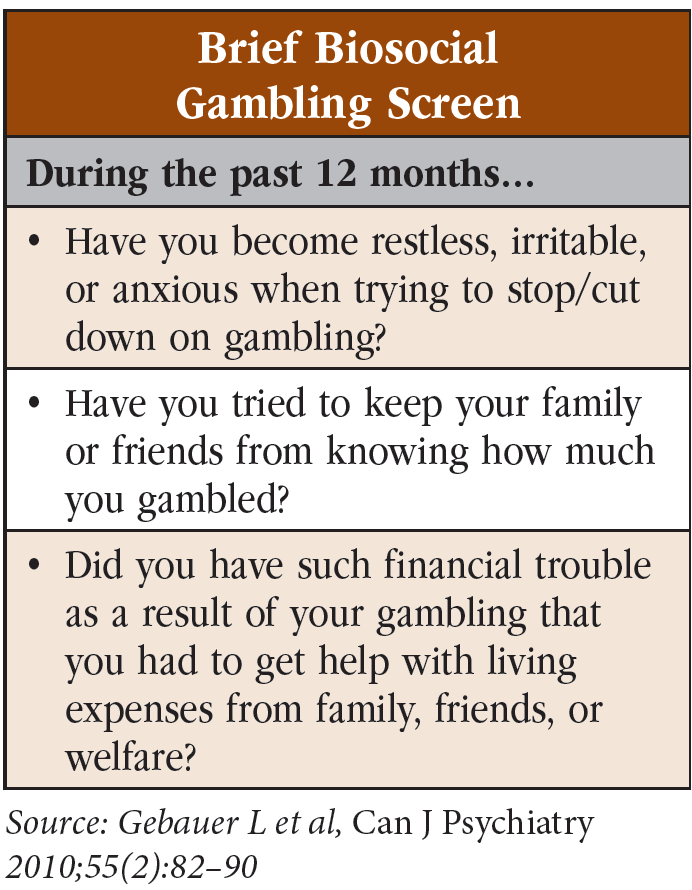

Dr. Fong: I recommend folding it into your intake or into your first few sessions. Start off simply: “How do you spend your money on entertainment?” “Over the last 12 months, have you ever spent money in a gambling setting such as a casino or at the racetrack?” If you prefer something more structured, the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen (BBGS) is a good three-item questionnaire (Dowling NA et al, Clinical Psychol Rev 2019;74:101784) (Editor’s note: See “Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen” table).

CATR: Let’s say a patient screens positive—what next?

Dr. Fong: Well, don’t just end it at the BBGS. Use the screener to open further conversation. I recommend starting with the basic logistical stuff: “Where and how do you gamble?” “What types of bets do you like?” “Where do you get money to gamble?” “Do you use brick-and-mortar casinos, mobile sports betting, internet gambling on the computer or phone?”

CATR: There are so many ways to gamble these days. The landscape must be very different than 20 or 30 years ago.

Dr. Fong: Absolutely—patients essentially have a casino in their pocket 24/7. Moreover, access to money is easier than ever before, and that can create rapid changes to one’s financial situation. Nearly anyone can hop online and get a high-interest payday loan. But obviously, these are not sound investments. People can rack up debt very quickly with these online predatory loans. Whenever a patient is talking a lot about their finances or how they’re stressed over money, that should immediately raise your antenna and you should ask about gambling.

CATR: Where do you go after asking the logistical questions?

Dr. Fong: Move on to the deeper questions: “What is it about gambling that draws you in?” “What is your relationship to money?” “How do you feel about winning/losing?” “Why do you think you continue to gamble?” “How do you deal with losses in your life?” Neglecting to ask these questions is a missed opportunity. They’re how you can start understanding what drives your patient. I recommend staying curious and nonjudgmental; it’s hard to go wrong if you keep that in mind.

CATR: That brings up treatment. What are the treatment options?

Dr. Fong: There are no FDA-approved medications for gambling disorder, and I don’t believe we’ll get one in the next 10 to 15 years. Most of our medication trials have not proven very successful. So one of the principal uses of medications is to treat co-occurring disorders. But there is some evidence for the opioid antagonists naltrexone and nalmefene (just recently available in the US as an opioid overdose reversal agent) in higher doses and N-acetylcysteine. I’ve found that medications can be particularly useful for patients with biological reactivity. I’ll ask, “Tell me what it’s like when you’re driving to the casino. What are you feeling? What are you thinking?” Someone with high biological reactivity might say, “I get butterflies in my stomach, my heart races, and my palms are sweaty.” There is work being done on other biological approaches such as rTMS, and other medications such as varenicline, acamprosate, and ondansetron. The data on these are either too early or too mixed to recommend them at this point. So, my biological approach usually boils down to naltrexone plus treatment of co-occurring psychiatric disorders.

CATR: What about nonmedication treatments?

Dr. Fong: There are a lot of psychotherapy options—over a dozen, in fact. We have evidence for motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and supportive therapy; they all work with similar effect sizes. Dr. Nancy Petry, a pioneer in gambling treatment, has developed a cognitive behavioral treatment specific to gambling disorder as well as a short one- or two-session brief behavioral therapy (Dowling et al, 2019). I mentioned that medication can be particularly helpful for patients with high biological reactivity. On the other hand, I tend to focus on psychotherapy for patients who describe dissociation. They might describe going to the casino as “going on autopilot” without even remembering how they got there.

CATR: What about the nonexpert? How might they go about treating patients with gambling disorder?

Dr. Fong: The longer I’ve been in this field, the simpler my approach has become, driven more by a whole-patient approach. I structure clinical conversations around SAMHSA’s four major dimensions that support a life in recovery: home, health, purpose, and community (www.tinyurl.com/2s7wt7dd). The initial goal is to reestablish healthy practices that have been neglected, such as sleep, nutrition, exercise, and stress management. You must balance physical health, mental health, and general well-being. Otherwise, gambling disorder is going to be very hard to overcome.

CATR: What about online resources?

Dr. Fong: There are telehealth options available for those who don’t have good access locally. For those who struggle with online gambling, there’s a software program called Gamban, which is an app you can install to block gambling websites (www.gamban.com). It’s not a standalone treatment, but it removes easy access to gambling, and I find it gives patients an opportunity to pause and ask themselves, “Is this really what I want to be doing?” There are a lot of online portals and self-help workbooks out there. One I am affiliated with is the UCLA Gambling Program (www.UCLAgamblingprogram.org), and we provide downloadable PDF materials for free. For providers who are particularly motivated, I recommend the national conferences put on by the National Council on Problem Gambling and the International Center for Responsible Gaming. Most states host their own educational conferences as well.

Dr. Fong: We haven’t discussed the importance of community yet, the importance of having a good treatment network. Peer support like Gamblers Anonymous (www.gamblersanonymous.org) and Gamblers in Recovery (www.gamblersinrecovery.com) can be enormously helpful. It shouldn’t be the only component of treatment, but it can be a good adjunct. And almost every state funds a form of gambling treatment, often free of charge. For families, I’d recommend Gam-Anon, which is a companion to Gamblers Anonymous. And anyone can call 1-800-GAMBLER, which is a resource hotline that offers advice to people throughout the country (Editor’s note: See “Gambling Addiction Resources” table for more).

CATR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Fong.

Timothy Fong, MD.

Timothy Fong, MD.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)