Quetiapine Reconsidered

Paul Riordan, MD. Assistant Consulting Professor of Psychiatry, Duke University. Dr. Riordan has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

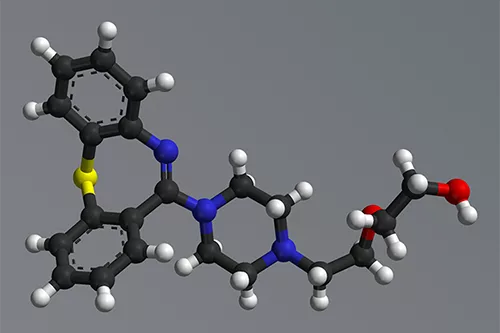

It is the best of drugs; it is the worst of drugs. Quetiapine (Seroquel) has benefits in some disorders that are unmatched by other medications, but it is also one of the most difficult antipsychotics to tolerate. In this article, I’ll look at where this medication fits and whether its numerous off-label uses are justifiable, including PTSD, generalized anxiety, insomnia, and delirium.

Different effects at different doses

Quetiapine is challenging to use because it acts differently at different doses. Why? It has markedly distinct binding affinities for different receptors. At low doses (25–150 mg), quetiapine binds first to the histamine 1 receptor, which drives its sedative properties. Unfortunately, quetiapine also has alpha 1 adrenergic and muscarinic 1 antagonism (“anticholinergic”) properties in this range, which contribute to sedation and cause the adverse side effects of dry mouth, dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, constipation, and urinary hesitancy.

At higher doses, those side effects start to plateau and more therapeutic properties kick in. At doses of 150–300 mg, quetiapine has serotonergic and noradrenergic properties, which is why it shines as an antidepressant in that range. Finally, quetiapine has antipsychotic properties, but only at doses of at least 300 mg, when it starts to antagonize the dopamine 2 receptor. This is why the average dose in schizophrenia is around 500 mg (Leucht S et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(4):342–353).

Mood and anxiety disorders

In mood disorders, quetiapine stands out as one of the two atypical antipsychotics with efficacy in both the manic and depressive phases, the other being cariprazine (Vraylar). But what really sets quetiapine apart is its efficacy in bipolar depression, which is about twice that of cariprazine’s, judging by their numbers needed to treat (NNT) of 6 vs 11. Lumateperone, lurasidone, and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination also have robust efficacy in bipolar depression, but these three lack evidence in mania (Kadakia A et al, BMC Psychiatry 2021;21(1):249).

When it comes to side effects, however, quetiapine is one of the worst offenders. Patients gained an average of 2.6 pounds in trials lasting less than two months, as compared to lurasidone at 0.53 pounds and aripiprazole at 0.44 pounds. Only olanzapine did worse at 6.35 pounds. Over the long term, one in five patients gained more than 7% of their body weight after nine or more months on quetiapine (Bak M et al, PloS One 2014;9(4):e94112).

In acute mania, antipsychotics are usually favored over lithium when rapid action is needed or when mixed features are prominent. Quetiapine’s antimanic efficacy is about average for the antipsychotic family, but some consider it first line for its ability to prevent postmanic depression. That’s an important consideration, as depression is much more common than mania throughout the lifespan in this illness. Surprisingly, no other antipsychotic has robust evidence in preventing bipolar depression, with the possible exception of asenapine (Szegedi A et al, Am J Psychiatry 2018;175(1):71–79).

In the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder, quetiapine works particularly well when combined with lithium, where it lowers the odds of recurrence four-fold over lithium alone (Nestsiarovich A et al, Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2022;54:75–89). Some of these benefits may be due to quetiapine’s effects on sleep, which are more than just sedating. Quetiapine is the only atypical antipsychotic with evidence to improve sleep quality.

Unipolar depression

In unipolar depression, quetiapine has FDA approval only as an augmenting agent, not as monotherapy. It is mildly helpful at doses of 200–300 mg with a small effect size of 0.32 and an NNT of roughly 7 (Davies P et al, Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;12(12):CD010557). There was a stark difference in dropout rates between the high and low doses in the unipolar studies, with no increase in dropouts at 150 mg/day but an 82% increased dropout risk at 300 mg/day.

Anxiety

In generalized anxiety disorder, a meta-analysis showed that quetiapine had the largest effect of all medications as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, edging out escitalopram, duloxetine, and even benzodiazepines. However, people taking quetiapine were also more likely to drop out of the study, with a 44% increased likelihood compared to placebo (Slee A et al, Lancet 2019;393(10173):768–777). That side effect burden caused the FDA to decline quetiapine’s application for approval in generalized anxiety, and we would only consider it third or fourth line for severe cases.

However, these anxiolytic properties are more useful in bipolar disorder, where there is a paucity of therapies for comorbid anxiety. Quetiapine reduced anxiety that was comorbid with a mood disorder in 20 out of 27 placebo-controlled trials (Crapanzano C et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2021;41(4):436–449). This benefit may extend to OCD, according to a small placebo-controlled trial that tested quetiapine 350 mg in patients with bipolar I disorder and OCD (Sahraian A et al, CNS Spectr 2021;1–5).

Schizophrenia

In schizophrenia, quetiapine is favored more for its relative lack of akathisia and Parkinsonism than its efficacy. Its effect size is in the medium range (0.4) but smaller than the effect size for clozapine (0.9), olanzapine (0.55), and risperidone (0.55). In addition, its metabolic profile is unfavorable; only clozapine and olanzapine have worse metabolic effects. Anticholinergic burden is another problem, particularly in the higher doses used for schizophrenia, as these side effects are linked to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia (Joshi YB et al, Am J Psychiatry 2021;178(9):838–847).

PTSD, delirium, and behavioral symptoms of dementia

While quetiapine is often used off-label for PTSD, delirium, and dementia, the quality of evidence for these indications is weak. Two placebo-controlled trials in delirium were negative, and quetiapine had little benefit in psychosis related to Parkinson’s dementia (Nikooie R et al, Ann Intern Med 2019;171(7):485–495; Jethwa KD et al, BJPsych Open 2015;1(1):27–33). Quetiapine fared a little better in PTSD, where it improved reexperiencing and hyperarousal (but, surprisingly, not sleep) in a randomized trial with 80 participants, most of whom were combat veterans (Villarreal G et al, Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(12):1205–1212).

How to use

In the outpatient setting, slowly titrating quetiapine by 50 mg every three to four days helps mitigate its most common side effects of somnolence, dry mouth, and dizziness. It’s best to stick to the target dose for each indication (see table), as higher doses led to more dropouts, particularly in the elderly. In the inpatient setting, going faster by 100 mg/day is often necessary to treat mania and psychosis. Avoid using with carbamazepine, which can render quetiapine inert, and watch for a little-known interaction with lamotrigine, which can reduce quetiapine levels by up to 30%.

Table. Quietiapine: Indications and Dosing

(Click to view full-sized PDF)

The XR formulation may be helpful if orthostatic hypotension is a problem, but it also has a slightly greater risk of morning fatigue. Quetiapine XR’s release mechanism can break down in the presence of food or alcohol, causing it to release all of its sedating ingredients at once. For that reason, it should be taken 30–60 minutes away from a large meal, and—to minimize morning fatigue—12 hours before the patient plans to wake up (Kishi T et al, J Psych Research 2019;115:121–128).

When quetiapine was first released, there was concern about its potential to cause serious arrhythmias like torsades de pointes by prolonging the QTc interval. However, not all QTc prolongation leads to serious arrhythmias, and it now appears that the risk of arrhythmias with quetiapine is much lower than once thought (Hasnain M et al, CNS Drugs 2014;28(10):887–920).

Carlat Verdict: Quetiapine is not for everyone, but its ability to prevent and treat bipolar depression makes it a good choice in this condition, particularly when the mood problems are severe or mixed with anxiety or insomnia. For other disorders, it doesn’t stand out from the pack, and its side effect burden makes it less desirable.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)