Home » Tips on Managing Medications With Adolescents

Tips on Managing Medications With Adolescents

November 1, 2017

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Jess Shatkin, MD

Vice chair for education and professor of child & adolescent psychiatry and pediatrics at the New York University School of Medicine. Author of Born to Be Wild: Why Teens Take Risks, and How We Can Help Keep Them Safe (Penguin Random House).

Dr. Shatkin has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Jess Shatkin, MD

Vice chair for education and professor of child & adolescent psychiatry and pediatrics at the New York University School of Medicine. Author of Born to Be Wild: Why Teens Take Risks, and How We Can Help Keep Them Safe (Penguin Random House).

Dr. Shatkin has disclosed that he has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

Discussing medications with adolescents can be challenging. In general, my approach during the initial evaluation is to have a first evaluation appointment with the parents alone to gather relevant history, and then bring the teen back for a separate and individual appointment. Oftentimes, however, and particularly with older teens, I will see the family together for the first visit, all members in one room, and then meet separately with the adolescent. I base my approach on what I learn by phone from the parents when they call for an appointment. Because there is so much variation in family structure and the problems that kids and families face, I find it’s important to maintain some flexibility in how I evaluate adolescents.

One thing I don’t want to do is leave adolescents in the waiting room while I’m talking to their parents. If the parents need to be seen alone without the child present, then I will do that at a separate time. The important thing is understanding where adolescents are coming from, and what they’re challenged by. Often, they’re struggling with some aspect of how they view themselves, and how they’re going to be independent from their parents. And so, helping them to see the medication as part of how they can manage on their own can be very empowering.

How do you decide when young people can handle their own medications? In my experience, this varies by age and diagnosis. With ADHD, for example, it’s difficult because these kids have terrible organizational skills, so getting them to even find their medicine or remember to take it is a big challenge. Therefore, I suggest that you initially work with parents on the following strategies:

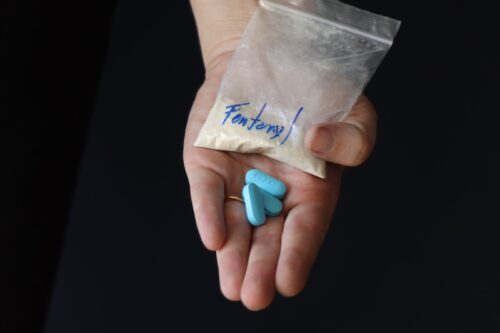

Drug diversion can also become a problem, especially with older kids prescribed stimulants. One potential solution is to prescribe a long-acting formulation, such as Adderall XR as opposed to Adderall IR—although some kids will still sell it to friends as a study drug (Martinez-Raga J et al, Ther Adv Drug Saf 2017;8(3):87–99). In conjunction, I will often say something like, “Listen, this is a medicine that some people like to borrow; they like to take it so they can stay up all night and study. So, you’ll get this medicine from me only once a month, and I don’t give early refills.” I tell this to the parents, too. If a family member tells me the medication accidentally got flushed down the toilet or something terrible happened, that’ll be addressed on a case-by-case basis, and I might give an early refill one time, but that’s it.

In terms of how teens should secure their meds while attending college, I generally will give some practical advice. Some colleagues recommend that students bring a lock box with a cable on it that they can secure under their bed, where they keep their wallet and their medicine.

In college, adolescents are in a time of transition, and some students very much want to remake themselves. I sometimes hear, “I don’t want to be that kid who takes the medication his parents tell him to take.” In addition, it’s key to make sure students can get the care they need at college. Because the college stressors may aggravate their symptoms, this is not the time for them to abruptly change or stop their treatment (Brinkman WB et al, American Pediatrics 2017, doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.005).

It’s also important to address the issue of substance abuse, which is very common in college. I tell kids that alcohol and marijuana will contribute to depression and anxiety; it will also distract them from learning and being involved in the sorts of activities that will help them grow into the person they want to be. But discussing this with teens requires some finesse.

I recommend you begin by making it clear that you don’t want them drinking at all while on the medication, and outline the risks associated with doing so. I also tell adolescents that, even though young people often don’t feel the immediate negative effects of drugs and hangovers as much as older people do, the negative impact upon their brains and neural tissue is far greater. At the same time, though, you also need to let them know that you understand they will want to go to college parties, where they might well be tempted to drink alcohol or smoke marijuana. Depending upon the patient, I may then give them some advice about harm reduction. This is not a perfect solution, but some teens may not feel they can be honest with you if you simply forbid them from drinking or smoking; they may instead just drink and skip their medication for fear of a terrible interaction. As their doctor, you need to know the truth about their behavior.

For example, I might suggest that a teen have a maximum of 2 drinks at a party, and that it’s imperative to drink 12 ounces of water between drinks. I explain that a “drink” is a 12-ounce beer, 4 ounces of wine, or a single shot of spirits. I also emphasize the importance of making a plan before they arrive at the party. Deciding in advance how much they will drink, or role playing how they will say no or not have a second or third drink, is a way to potentially reduce harm with the acknowledgement that they will otherwise be without any guideposts to follow.

It is also important to talk about serious drug-drug interactions, such as serotonergic interactions between SSRI/ SNRIs and MDMA/ecstasy, while we monitor as usual for severe medication problems such as agitation and withdrawal, either of which could increase suicidality (Groenman AP et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56(7):556–569).

Some clinicians find that, as their patients grow into their late teens and early 20s, they don’t require as much medication. In my experience, there are at least two reasons for this. First, younger kids metabolize drugs more quickly than teens and young adults. I sometimes think of kids as hummingbirds, and they slow down as they grow older. We certainly see this with ADHD medicines, where dosing is much higher per kilogram of body weight in younger people. I sometimes see this with antidepressants, too.

Aside from changes in metabolism, there are also psychological changes that may explain why dosing decreases. As young adults develop more insight into their behavior, learn skills through psychotherapy that help them regulate their emotions, establish a good network of social support, and develop more self-efficacy, we sometimes find that they require less medication. Conversely, however, for those who don’t develop these supports, continued higher dose treatment may remain essential.

CCPR Verdict: Figuring out how to help young people handle their own medications can be a challenge for both parents and psychiatrists. Keeping kids organized and responsible when it comes to taking and securing their meds involves careful consideration, specific strategies, and counseling.

Child PsychiatryOne thing I don’t want to do is leave adolescents in the waiting room while I’m talking to their parents. If the parents need to be seen alone without the child present, then I will do that at a separate time. The important thing is understanding where adolescents are coming from, and what they’re challenged by. Often, they’re struggling with some aspect of how they view themselves, and how they’re going to be independent from their parents. And so, helping them to see the medication as part of how they can manage on their own can be very empowering.

How do you decide when young people can handle their own medications? In my experience, this varies by age and diagnosis. With ADHD, for example, it’s difficult because these kids have terrible organizational skills, so getting them to even find their medicine or remember to take it is a big challenge. Therefore, I suggest that you initially work with parents on the following strategies:

- Have parents help their child store the medicine in a consistent place, where it can always be found. As any parent knows, kids can be prone to misplacing things that are important. So, parents might try placing the medication by the toothbrush (presuming the child always brushes each morning!) or putting it out with breakfast.

- Encourage parents to allow their child to take the medicine on their own—but also provide parents with ways to check that their child took the medicine. Some kids will fight parents on this, so I suggest that parents tie taking the medication to privileges that their kids want, such as using the car or keeping their smartphone. Also, kids must be aware of the importance of keeping up with their treatment. In the case of ADHD, for example, driving can be quite dangerous if kids are not taking their medication. So, these issues must be explained. Kids need to know how many more automobile and other accidents happen to people who do not take their ADHD treatment as prescribed.

- Have parents and children come in more frequently for therapy to address any concerns about taking medication. Work with parents to reinforce the value of taking the medication.

Drug diversion can also become a problem, especially with older kids prescribed stimulants. One potential solution is to prescribe a long-acting formulation, such as Adderall XR as opposed to Adderall IR—although some kids will still sell it to friends as a study drug (Martinez-Raga J et al, Ther Adv Drug Saf 2017;8(3):87–99). In conjunction, I will often say something like, “Listen, this is a medicine that some people like to borrow; they like to take it so they can stay up all night and study. So, you’ll get this medicine from me only once a month, and I don’t give early refills.” I tell this to the parents, too. If a family member tells me the medication accidentally got flushed down the toilet or something terrible happened, that’ll be addressed on a case-by-case basis, and I might give an early refill one time, but that’s it.

In terms of how teens should secure their meds while attending college, I generally will give some practical advice. Some colleagues recommend that students bring a lock box with a cable on it that they can secure under their bed, where they keep their wallet and their medicine.

In college, adolescents are in a time of transition, and some students very much want to remake themselves. I sometimes hear, “I don’t want to be that kid who takes the medication his parents tell him to take.” In addition, it’s key to make sure students can get the care they need at college. Because the college stressors may aggravate their symptoms, this is not the time for them to abruptly change or stop their treatment (Brinkman WB et al, American Pediatrics 2017, doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.005).

It’s also important to address the issue of substance abuse, which is very common in college. I tell kids that alcohol and marijuana will contribute to depression and anxiety; it will also distract them from learning and being involved in the sorts of activities that will help them grow into the person they want to be. But discussing this with teens requires some finesse.

I recommend you begin by making it clear that you don’t want them drinking at all while on the medication, and outline the risks associated with doing so. I also tell adolescents that, even though young people often don’t feel the immediate negative effects of drugs and hangovers as much as older people do, the negative impact upon their brains and neural tissue is far greater. At the same time, though, you also need to let them know that you understand they will want to go to college parties, where they might well be tempted to drink alcohol or smoke marijuana. Depending upon the patient, I may then give them some advice about harm reduction. This is not a perfect solution, but some teens may not feel they can be honest with you if you simply forbid them from drinking or smoking; they may instead just drink and skip their medication for fear of a terrible interaction. As their doctor, you need to know the truth about their behavior.

For example, I might suggest that a teen have a maximum of 2 drinks at a party, and that it’s imperative to drink 12 ounces of water between drinks. I explain that a “drink” is a 12-ounce beer, 4 ounces of wine, or a single shot of spirits. I also emphasize the importance of making a plan before they arrive at the party. Deciding in advance how much they will drink, or role playing how they will say no or not have a second or third drink, is a way to potentially reduce harm with the acknowledgement that they will otherwise be without any guideposts to follow.

It is also important to talk about serious drug-drug interactions, such as serotonergic interactions between SSRI/ SNRIs and MDMA/ecstasy, while we monitor as usual for severe medication problems such as agitation and withdrawal, either of which could increase suicidality (Groenman AP et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56(7):556–569).

Some clinicians find that, as their patients grow into their late teens and early 20s, they don’t require as much medication. In my experience, there are at least two reasons for this. First, younger kids metabolize drugs more quickly than teens and young adults. I sometimes think of kids as hummingbirds, and they slow down as they grow older. We certainly see this with ADHD medicines, where dosing is much higher per kilogram of body weight in younger people. I sometimes see this with antidepressants, too.

Aside from changes in metabolism, there are also psychological changes that may explain why dosing decreases. As young adults develop more insight into their behavior, learn skills through psychotherapy that help them regulate their emotions, establish a good network of social support, and develop more self-efficacy, we sometimes find that they require less medication. Conversely, however, for those who don’t develop these supports, continued higher dose treatment may remain essential.

CCPR Verdict: Figuring out how to help young people handle their own medications can be a challenge for both parents and psychiatrists. Keeping kids organized and responsible when it comes to taking and securing their meds involves careful consideration, specific strategies, and counseling.

KEYWORDS child-psychiatry practice-tools-and-tips

Issue Date: November 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)