Home » Treatment of First Episode Psychosis in College Students: It Takes a Team

Treatment of First Episode Psychosis in College Students: It Takes a Team

August 1, 2017

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Marcia Morris, MD

Psychiatrist at the University of Florida. Author of The Campus Cure: A Parent’s Guide to Mental Health and Wellness for College Students, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (forthcoming 2018)

Dr. Morris has disclosed that she has no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

You are a psychiatrist working in a college student healthcare center when Anna, a junior, comes to your office escorted by her resident advisor. Anna describes feeling severely depressed. Sleeping excessively, she has missed most of her classes over the last two weeks. For the past week, she has heard voices telling her she is worthless and will never amount to anything. When she walks on campus, she thinks she sees former middle school classmates who used to bully her and wonders if they are going to harm her. She has started to think she would be better off dead, but denies any current plans to harm herself.

Evaluation

Evaluating a first episode of psychosis in college students is challenging—it’s not clear from the outset if the episode will represent a one-time occurrence or the start of a lifelong illness. The differential diagnosis is large and includes depression with psychotic features, bipolar disorder, a primary psychotic disorder like schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, drug-induced psychosis, and transient psychotic episodes. Here are the five ways I try to narrow down the possibilities during an initial evaluation.

Comprehensive treatment approach

My approach to treating psychosis in college students is aligned with a comprehensive treatment system demonstrated by the RAISE study to improve functional outcomes in adults (mean age of 23) with first episode psychosis (Kane JM et al, Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:(4):362–372). Conducted at community mental health centers over a two-year period, the RAISE study enrolled 223 participants in the NAVIGATE system of manual-based care, and 181 in usual care. NAVIGATE consisted of personalized medication management, family psychoeducation, resilience-focused individual therapy, and supported employment and education. (See TCPR, November/December 2015 for a Research Update on NAVIGATE for psychosis.) The NAVIGATE recipients had significantly better outcomes: They were more likely to stay in treatment, had fewer symptoms, and were more likely to participate in work and school.

The NAVIGATE family education and therapy model is particularly relevant to working with college students. After a few introductory sessions, patients and their families meet with a counselor for 10–12 weekly sessions to focus on improved communication among family members, relapse prevention, and suicide prevention. Family members are encouraged to reinforce progress by observing and praising what the patient is doing well in life, which could be volunteering while taking a semester off or registering for a few classes. These weekly sessions are followed by monthly check-ins, either in person or by phone.

The NAVIGATE approach also has a supported education and employment (SEE) specialist working closely with the patient to encourage engagement in work or education. The SEE specialist will regularly meet with the patient to set a goal of finding employment or education within the next three months. The specialist may go with the patient to the job interview or to visit the campus if the patient needs additional support and will continue to provide support even after school or a job begins.

It’s important to note that while the RAISE study constitutes an ideal kind of treatment, you might not be able to offer all aspects of it when resources are limited, either in the college setting or after a student takes time off from college. But as orchestra leader, you do what you can to put into place as comprehensive a plan as possible, so you can at least use the RAISE points as guideposts. You can view the manuals for the NAVIGATE system online at http://www.raiseetp.org/studymanuals/index.cfm.

Evaluate safety/level of treatment needed

The first stage of treatment is to decide what sort of treatment environment your patient needs—outpatient, inpatient, or something in between? Concerned about Anna’s auditory hallucinations and passive suicidal thoughts, I asked her to describe the voices in more detail. Anna said unknown men’s voices told her that she was worthless and her life did not matter. I asked if they ever ordered her to harm herself, and she said no, but she admitted thinking it might be easier if she were dead. She would not harm herself now, she said, but if she continued to experience her current level of depression, she might consider suicide in the future. Although Anna described a potential future risk of suicide, I concluded that she was not in imminent danger of harming herself, and because her mother was able to stay with her, I felt comfortable seeing her as an outpatient. Had there not been a parent nearby, I might have recommended that she stay in a peer respite unit, a supportive inpatient environment that is not as restrictive as a locked psychiatric unit.

Start appropriate medication

To treat psychotic depression, I often prescribe an antidepressant and a low dose of an antipsychotic that is not overly sedating. Good non-sedating options include risperidone, aripiprazole, and lurasidone. I have found lurasidone quite effective for bipolar depression in students, although this medication is costly and insurance companies will not always cover it. For students with psychosis and prominent insomnia, I will often use quetiapine. I prescribed Anna escitalopram as well as a low dose of risperidone.

Get the family involved

Parent support through phone calls or visits can be critical when students are feeling overwhelmed or struggling with suicidal thoughts. Parents can also act as consultants, helping students decide whether to stay in school or facilitating the process of taking a medical leave. I recommended that Anna’s mother stay in town for a few days until Anna felt safe and showed some response to her medications. I find this to be a reasonable alternative to hospitalization, which poses its own challenges. Anna confirmed that if her voices escalated to the point that she felt she would hurt herself, she would tell her mother and would agree to hospitalization.

Ensure the patient receives psychotherapy

Encourage your patient to undergo individual and/or group therapy with a therapist who has experience working with people with psychosis. Anna participated in an educational group called the Wellness Recovery Action Plan® (WRAP®) (http://mentalhealthrecovery.com/wrap-is/). Each group session focused on specific aspects of wellness and recovery: identifying wellness tools that could keep her feeling good most days, understanding the triggers that bring on symptoms, and creating action plans for when symptoms return or escalate. Anna developed a plan—if the voices became more threatening, she would at first try to distract herself by spending time with her roommate. Next, she would call her mother or a friend. She would also contact our counseling center on-call system or see me the next day about a medication adjustment. Knowing she had a plan made her feel more empowered to cope with the voices.

Ensure peer support

Peer support that focuses on wellness and recovery is helpful for young adults with chronic psychotic symptoms. Encourage your patient to join Active Minds (http://www.activeminds.org) or any other peer support group on campus. You can link your patient to community peer support groups offered by organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (http://nami.org) and the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (http://dbsalliance.org). Anna obtained peer support in her WRAP group and continued to connect with members even after the group sessions had ended.

Consider vocational rehab

Vocational rehab programs also exist in many communities to link patients who experience chronic mental health issues to meaningful work. Campus case managers can recommend programs if your patient needs to take time off from school.

Work closely with the college

Some students may be unable to remain in college due to psychotic symptoms. They may not be adherent to medication and therapy, they may continue to use drugs that exacerbate their symptoms, or they may have a more severe form of psychosis that is not responsive to treatment. Contacting the dean of students’ office or a case manager in the counseling center directly can help with coordinating a reduced course load or other accommodations, or facilitating the patient’s transition to more intensive treatment, such as a partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient program.

In Anna’s case, I called the dean of students’ office and helped Anna and her mother make an appointment with a case manager to decide if she should reduce her course load or medically withdraw from the semester. I told Anna that I could write a letter to support whatever decision she made. Anna thought she would be okay if she dropped two of her classes; she had kept up with work in the other two. I also recommended Anna register with the campus disability resource center so she could get extra support and coaching regarding her school work.

Offer hope

It is critical to offer patients hope. The suicide rate for people with psychotic disorders is highest in the first year after diagnosis (Ventriglio A et al, Front Psychiatry 2016;7:116), so you want to throw out the lifeline of hope to attenuate suicidal urges. College students may feel hopeless if they are not able to keep up with academic work due to cognitive difficulties stemming from psychosis or medication. Fortunately, the comprehensive treatment outlined above does improve outcomes. I let Anna and her mother know that I have successfully worked with other students with similar symptoms. Some have had to reduce their course load or take a semester off from school, while others have not had to take any time off at all.

CCPR Verdict: There is something of a wild card aspect to cases involving psychosis, because you don’t know up front if the patient is experiencing a one-time episode or the first sign of a chronic, ongoing condition. Still, regardless of the particular path needed, providing a comprehensive and collaborative approach offers our patients the best chance of a mindset of recovery and purpose.

Child PsychiatryEvaluation

Evaluating a first episode of psychosis in college students is challenging—it’s not clear from the outset if the episode will represent a one-time occurrence or the start of a lifelong illness. The differential diagnosis is large and includes depression with psychotic features, bipolar disorder, a primary psychotic disorder like schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, drug-induced psychosis, and transient psychotic episodes. Here are the five ways I try to narrow down the possibilities during an initial evaluation.

-

Develop an alliance

College students with psychosis who come into my office, whether on their own or encouraged by university personnel, are usually in a great deal of distress. The sources of distress are generally two-fold: the experience of psychosis itself and the accompanying academic difficulties. You can best develop an alliance with college students by rapidly acknowledging their distress and informing them you will work together to decrease that distress and improve academic functioning.When I first met with Anna, she spoke minimally while fearfully staring out the window. I gently asked her if she was concerned about anything outside. She said she had the feeling that classmates from middle school were hiding in the bushes outside and were following her. Afraid to go to class, she had fallen significantly behind in her work. I told Anna I understood how distressed she must be feeling, and that I would work with her to help her feel safe so she could get to class and achieve her academic goals. Anna sighed, looked at me tearfully, and said, “I’ll be really glad if you can help me.”

-

Ask targeted questions to narrow down the diagnosis

To distinguish between a primary psychotic disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features, ask about the patient’s current and past history of depressive, manic or hypomanic, and psychotic symptoms. I asked Anna if her feelings of being followed were new or if she’d had them for a long time. She revealed that she had been cyberstalked and sometimes physically harassed in middle school, but said these events had stopped when she moved to another school; the feelings of being followed had only resurfaced recently. I asked Anna if she had felt either revved up or sad before the voices started. She told me she had been feeling depressed the whole semester, but started feeling worse a few weeks ago and began sleeping all the time. When asked if she had ever been treated for depression before this episode, Anna said she had taken Lexapro during high school for about 6 months. I made a diagnosis of depression with psychotic features based on the recurrence of depression and the new onset of psychotic symptoms during an episode of depression.

-

Consider the developmental and family history

While we often consider psychosis to be mainly a biologically based disorder, it’s important to probe for potential developmental aspects. I find it helpful to bring parents into this discussion if possible. Anna’s mother confirmed that Anna was severely bullied in middle school. Research has shown that being bullied increases the risk of depression and psychotic symptoms (Wolke D et al, Psychological Medicine 2014;44:9(10):2199–2211), and indeed some of Anna’s psychotic symptoms centered on bullying. In addition, Anna’s uncle had a diagnosis of schizophrenia; having a second-degree relative with schizophrenia increases the lifetime risk of having this disorder to 4%, versus 1% for others (Gejman P et al, Psychiatr Clini North Am 2010;33(1):35–66). While Anna’s diagnosis was consistent with depression with psychotic features, schizophrenia should be considered in a patient’s differential diagnosis.

-

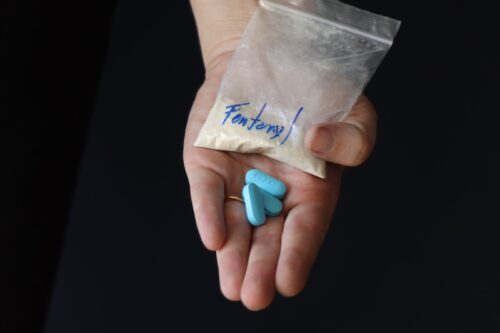

Probe to see if drugs could have played a role in the psychosis

In my experience, psychosis in college students is frequently associated with drug use. Common culprits include overuse of recreational psychostimulants, chronic use of cannabis with high THC content, and regular use of hallucinogens like LSD. In fact, the most complicated episodes of psychosis I have treated are recurrent episodes in students who use one or several drugs. When I inquired about any substance use, Anna denied drinking or using drugs.

-

Rule out medical causes of psychosis

While medical causes of psychosis are rare in the college-aged population, I recommend ordering a standard battery of tests in any case of first episode psychosis. This includes a comprehensive metabolic panel (electrolytes, renal function tests, liver function tests), glycosylated hemoglobin, thyroid function tests, lipid panel, B12, folate, and urine drug screen. Consider testing for syphilis, HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C if the patient is sexually active and ordering a CT scan or an MRI, as well as a neurology referral, if a student has an unusual clinical picture or describes neurological symptoms like worsening headaches or seizure-like movements.

Comprehensive treatment approach

My approach to treating psychosis in college students is aligned with a comprehensive treatment system demonstrated by the RAISE study to improve functional outcomes in adults (mean age of 23) with first episode psychosis (Kane JM et al, Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:(4):362–372). Conducted at community mental health centers over a two-year period, the RAISE study enrolled 223 participants in the NAVIGATE system of manual-based care, and 181 in usual care. NAVIGATE consisted of personalized medication management, family psychoeducation, resilience-focused individual therapy, and supported employment and education. (See TCPR, November/December 2015 for a Research Update on NAVIGATE for psychosis.) The NAVIGATE recipients had significantly better outcomes: They were more likely to stay in treatment, had fewer symptoms, and were more likely to participate in work and school.

The NAVIGATE family education and therapy model is particularly relevant to working with college students. After a few introductory sessions, patients and their families meet with a counselor for 10–12 weekly sessions to focus on improved communication among family members, relapse prevention, and suicide prevention. Family members are encouraged to reinforce progress by observing and praising what the patient is doing well in life, which could be volunteering while taking a semester off or registering for a few classes. These weekly sessions are followed by monthly check-ins, either in person or by phone.

The NAVIGATE approach also has a supported education and employment (SEE) specialist working closely with the patient to encourage engagement in work or education. The SEE specialist will regularly meet with the patient to set a goal of finding employment or education within the next three months. The specialist may go with the patient to the job interview or to visit the campus if the patient needs additional support and will continue to provide support even after school or a job begins.

It’s important to note that while the RAISE study constitutes an ideal kind of treatment, you might not be able to offer all aspects of it when resources are limited, either in the college setting or after a student takes time off from college. But as orchestra leader, you do what you can to put into place as comprehensive a plan as possible, so you can at least use the RAISE points as guideposts. You can view the manuals for the NAVIGATE system online at http://www.raiseetp.org/studymanuals/index.cfm.

Evaluate safety/level of treatment needed

The first stage of treatment is to decide what sort of treatment environment your patient needs—outpatient, inpatient, or something in between? Concerned about Anna’s auditory hallucinations and passive suicidal thoughts, I asked her to describe the voices in more detail. Anna said unknown men’s voices told her that she was worthless and her life did not matter. I asked if they ever ordered her to harm herself, and she said no, but she admitted thinking it might be easier if she were dead. She would not harm herself now, she said, but if she continued to experience her current level of depression, she might consider suicide in the future. Although Anna described a potential future risk of suicide, I concluded that she was not in imminent danger of harming herself, and because her mother was able to stay with her, I felt comfortable seeing her as an outpatient. Had there not been a parent nearby, I might have recommended that she stay in a peer respite unit, a supportive inpatient environment that is not as restrictive as a locked psychiatric unit.

Start appropriate medication

To treat psychotic depression, I often prescribe an antidepressant and a low dose of an antipsychotic that is not overly sedating. Good non-sedating options include risperidone, aripiprazole, and lurasidone. I have found lurasidone quite effective for bipolar depression in students, although this medication is costly and insurance companies will not always cover it. For students with psychosis and prominent insomnia, I will often use quetiapine. I prescribed Anna escitalopram as well as a low dose of risperidone.

Get the family involved

Parent support through phone calls or visits can be critical when students are feeling overwhelmed or struggling with suicidal thoughts. Parents can also act as consultants, helping students decide whether to stay in school or facilitating the process of taking a medical leave. I recommended that Anna’s mother stay in town for a few days until Anna felt safe and showed some response to her medications. I find this to be a reasonable alternative to hospitalization, which poses its own challenges. Anna confirmed that if her voices escalated to the point that she felt she would hurt herself, she would tell her mother and would agree to hospitalization.

Ensure the patient receives psychotherapy

Encourage your patient to undergo individual and/or group therapy with a therapist who has experience working with people with psychosis. Anna participated in an educational group called the Wellness Recovery Action Plan® (WRAP®) (http://mentalhealthrecovery.com/wrap-is/). Each group session focused on specific aspects of wellness and recovery: identifying wellness tools that could keep her feeling good most days, understanding the triggers that bring on symptoms, and creating action plans for when symptoms return or escalate. Anna developed a plan—if the voices became more threatening, she would at first try to distract herself by spending time with her roommate. Next, she would call her mother or a friend. She would also contact our counseling center on-call system or see me the next day about a medication adjustment. Knowing she had a plan made her feel more empowered to cope with the voices.

Ensure peer support

Peer support that focuses on wellness and recovery is helpful for young adults with chronic psychotic symptoms. Encourage your patient to join Active Minds (http://www.activeminds.org) or any other peer support group on campus. You can link your patient to community peer support groups offered by organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (http://nami.org) and the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (http://dbsalliance.org). Anna obtained peer support in her WRAP group and continued to connect with members even after the group sessions had ended.

Consider vocational rehab

Vocational rehab programs also exist in many communities to link patients who experience chronic mental health issues to meaningful work. Campus case managers can recommend programs if your patient needs to take time off from school.

Work closely with the college

Some students may be unable to remain in college due to psychotic symptoms. They may not be adherent to medication and therapy, they may continue to use drugs that exacerbate their symptoms, or they may have a more severe form of psychosis that is not responsive to treatment. Contacting the dean of students’ office or a case manager in the counseling center directly can help with coordinating a reduced course load or other accommodations, or facilitating the patient’s transition to more intensive treatment, such as a partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient program.

In Anna’s case, I called the dean of students’ office and helped Anna and her mother make an appointment with a case manager to decide if she should reduce her course load or medically withdraw from the semester. I told Anna that I could write a letter to support whatever decision she made. Anna thought she would be okay if she dropped two of her classes; she had kept up with work in the other two. I also recommended Anna register with the campus disability resource center so she could get extra support and coaching regarding her school work.

Offer hope

It is critical to offer patients hope. The suicide rate for people with psychotic disorders is highest in the first year after diagnosis (Ventriglio A et al, Front Psychiatry 2016;7:116), so you want to throw out the lifeline of hope to attenuate suicidal urges. College students may feel hopeless if they are not able to keep up with academic work due to cognitive difficulties stemming from psychosis or medication. Fortunately, the comprehensive treatment outlined above does improve outcomes. I let Anna and her mother know that I have successfully worked with other students with similar symptoms. Some have had to reduce their course load or take a semester off from school, while others have not had to take any time off at all.

CCPR Verdict: There is something of a wild card aspect to cases involving psychosis, because you don’t know up front if the patient is experiencing a one-time episode or the first sign of a chronic, ongoing condition. Still, regardless of the particular path needed, providing a comprehensive and collaborative approach offers our patients the best chance of a mindset of recovery and purpose.

Issue Date: August 1, 2017

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)