Home » Treating Transgender Children and Teens

Treating Transgender Children and Teens

September 1, 2014

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Daniel Medeiros, MD

There’s been lots of attention focused lately on the transgender population, from Medicare lifting the ban on transgender surgical procedures to TV star Neil Patrick Harris playing a transgender entertainer in Hedwig and the Angry Inch on Broadway.

Transgender rights are currently seen as the next frontier for equal rights. But from a practical standpoint, what do we do when a family comes to us with a child with gender variant expression?

Psychosocial Concerns

Transgender is defined as a person who feels that their gender identity does not match the gender assigned at birth. The prevalence in the US is low, but hardly negligible: it is estimated that 0.3% of adults, or close to one million people, identify as transgender (Stroumsa D, Am J Public Health 2014;104(3):e38). There are no reliable prevalence figures for children.

Life is not easy for the transgendered, at any age, because they deal with significant discrimination and stigma, which leads to a high prevalence of psychosocial problems. Transgender people have a particularly high likelihood of using drugs, alcohol, or smoking as a way to cope with discrimination. They are at increased risk of being victims of violence (including homicide) and suicide. For example, one study noted a 41% lifetime suicide attempt rate, compared to 1.6% in the general population (Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey 2011; http://bit.ly/1teXC7Y).

In addition, transgender people, particularly those of color and of low income, encounter significant discrimination in healthcare settings. One study found 19% reported being denied healthcare by a provider because of their gender identity, and 28% reported verbal harassment in a medical setting (Injustice at Every Turn, op.cit).

Treating Transgender Teens

The most common psychiatric issue that you will see in transgender teens is “gender dysphoria.” This is defined in DSM-5 as “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, of at least six month’s duration,” in addition to the usual stipulation of “clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning” (American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Addition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The change in definition from DSM-IV’s Gender Identity Disorder (GID) to the DSM-5’s Gender Dysphoria was a compromise, as many in the transgender community did not want any diagnosis in DSM-5, in the same way homosexuality was dropped as a diagnosis in DSM-III. Others wanted to keep a diagnosis, as psychiatrists are currently gatekeepers for transition surgery and a diagnosis is necessary for billing and insurance reimbursement.

In DSM-IV, GID was in the chapter of sexual disorders, which included sexual dysfunctions and paraphilias. Besides relabeling from a disorder to a less stigmatizing dysphoria, Gender Dysphoria is also now in a separate chapter in DSM-5.

There are two diagnoses: Gender Dysphoria in Children (code 302.6) and Gender Dysphoria in Adolescents and Adults (code 302.85). Both diagnoses require “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, of at least six month’s duration manifested by criteria (six of eight for children, two of six for adolescents/adults), and clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning” (American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Addition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

According to this definition, not every transgender person meets criteria to qualify for a gender dysphoria diagnosis.

Gender dysphoria is often caused by the teen’s struggle with gender identity and social difficulties such as the lack of acceptance from their peers.

A good approach to working with these teens is to start by meeting with the youth individually, which often entails helping him or her cope with the coming out process. Only later is the family involved, because the teen must be emotionally prepared to discuss the issue with family and only when it is safe to do so. Parental acceptance is its own process, often requiring family therapy. This is a crucial part of treatment, since being rejected by parents increases the risk of attempted suicide, depression, use of illegal drugs, and unprotected sex (Ryan C et al, Pediatrics 2009;123(1):346–352). I will generally tell parents directly that family acceptance is one of the best “treatments” for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) teens.

In working directly with adolescents, I emphasize that I accept their gender identity. It’s important that teachers and peers refer to them by their preferred name and pronouns, and that they understand and accept that some teens may associate a gay identity with taking on some gender atypical behaviors. For example, they might experiment with cross-dressing or may take on an opposite gender name.

In addition to discussing social adjustment issues, you should also ask your patient whether they use hormones or would like to use them. Very few physicians are willing to provide cross-gender hormones or puberty-suppressing hormones, even if a psychiatrist is part of the treatment team. You may need to be your patients advocate to find a physician willing to provide hormone treatment. It is generally accepted that the earlier the transition, before development of secondary sex characteristics, the higher the chances of a successful gender transition, leading to a better quality of life. Teens who cannot find a doctor to prescribe hormones may access street hormones, with the risk of unclean needles (HIV, hepatitis) and inappropriate hormones/dosages.

Gender identity: a person’s internal sense of being male, female, or something else

Gender expression: the way a person expresses their sense of gender identity (through hair, clothes, etc.)

Gender non-conforming/variant: a person whose gender expression differs from how their family, culture, or society expects

Transgender: a person who feels that their gender identity does not match the gender assigned at birth (also: male to female (MtF), female to male (FtM), transman, transwoman)

Sexual orientation: a person’s attraction to others, usually classified as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual

Cisgender: Someone who identifies with the gender they were assigned at birth

Special Considerations in Treating Children

Although prepubertal children with gender dysphoria may show gender atypical behavior ‘from birth’, they often don’t present for treatment until they begin school due to social conflict. Although parents vary in their willingness to allow their children to explore gender variant behavior, the issue often doesn’t escalate until the child expresses him or herself in public, such as in school. Families may come to treatment when parents either cannot tolerate or don’t know how to approach the issue, or when the child begins to have conflicts with school peers, including bullying. Many of these children present with anxiety and depression that require treatment.

Treatment of gender dysphoria in prepubertal children is controversial. Hormone treatments can lead to irreversible changes. There is no consensus within the medical community on how to make such treatment decisions.

Transitioning to another gender is generally separated into three phases: reversible, partially reversible, and irreversible.

Reversible changes can be implemented at any age and include adoption of preferred gender hairstyles, clothing, play, and name. By puberty, children can be given puberty suppressing hormones so they can delay further intervention until they are more capable of providing proper assent/consent (Olson J et al, Arch Ped Adolesc Med 2011;165(2):171–176).

Partially reversible treatments consist of providing cross-gender hormones. Current guidelines suggest age 16 as generally the most appropriate age to begin this in order to bypass development of the secondary sexual characteristics of the natal gender, which affect voice, height, facial hair growth, and breast development. Providing estradiol will induce irreversible breast development, while testosterone will induce irreversible clitoral enlargement and a drop in the voice (Olson J et al, op.cit).

The irreversible phase consists of the multiple surgical procedures used to create a more gender congruent appearance. Many transgender people do not have genital surgery for reasons that may include the expense, concern about sexual function/satisfaction, the belief that genitals do not define identity, or comfort in not being in a gender binary (ie, third gender, androgynous, gender queer, nongendered, etc).

There are currently three approaches to treatment of these children: corrective, supportive, and affirmative (Olson J et al, Arch Ped Adolesc Med 2011;165(2):171–176).

Corrective treatment. Since 1984, the corrective approach has been the standard clinical approach and most researched, using strategies that aim to align gender identity with biological sex. However, many experts express concern over the harm done to youth by invalidating their sense of self and note that this approach is “unscientific, unethical, and misguided, comparable to reparative therapy for homosexuality” (Drescher J, LGBT Health 2014;1(1):10–14).

Supportive therapy takes a ‘wait and see’ approach and does not focus on gender specifically, but may focus on anxiety or depression, and helping families protect their children from bullying by working with the school system. You neither validate nor invalidate the patient’s expressed gender identity. You simply work with the negative consequences as they experience them.

In the affirmative approach, you support the child and encourage active exploration of gender identity. You talk to the parents about the appropriateness of gender transition in some children. Over the past several years there have been more first-hand accounts of parents supporting their young gender variant children, advocating that their child be allowed to attend school with their chosen gender identity and name, beginning as early as elementary school (Gulli C. What Happens When Your Son Tells You He’s Really a Girl? MacLean’s January 14, 2013 [http://bit.ly/1nLZekd]). Sometimes this means needing to move to a new school/neighborhood/state as the child ends one school year in one gender and enters the new school year transitioned. Critics of this approach believe supporting gender transition in childhood can inappropriately encourage young people to persist in efforts to change genders (Drescher J, op.cit).

It is difficult to know what is the “right” approach for these children, and you have to judge each case on its own merits, being aware that you may have your own biases. For example, which is the better outcome: to be a happy transgender adult or to be a gay or heterosexual cisgender adult who may have lifelong issues with gender identity?

In the absence of scientific consensus, my approach is to pay attention to the extremes. I have seen a few cases where parents are strongly opposed to raising a child who may become a transgender or homosexual. In these cases, my role is to help the parents become more accepting of the different possible outcomes, providing them with resources to broaden their viewpoint. PFLAG [Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays] is one resource that provides support to families (http://community.pflag.org/). At the other extreme, parents may be too many steps ahead of their child regarding gender transition. In order to adjust to a new gender, some parents may choose to change the environment so the child presents as a new student in the preferred gender, as opposed to transitioning in the same environment. New peers then don’t know that this was someone of an opposite gender previously. However, several studies show moving/changing schools can be traumatic, especially for vulnerable children. In these cases, I may encourage the parents to slow down the transitioning process, allowing the child to take more of a lead.

Ultimately, the most crucial message you can give parents is that these are their children, they are special and unique, and they deserve to live authentic and happy lives.

Child PsychiatryTransgender rights are currently seen as the next frontier for equal rights. But from a practical standpoint, what do we do when a family comes to us with a child with gender variant expression?

Psychosocial Concerns

Transgender is defined as a person who feels that their gender identity does not match the gender assigned at birth. The prevalence in the US is low, but hardly negligible: it is estimated that 0.3% of adults, or close to one million people, identify as transgender (Stroumsa D, Am J Public Health 2014;104(3):e38). There are no reliable prevalence figures for children.

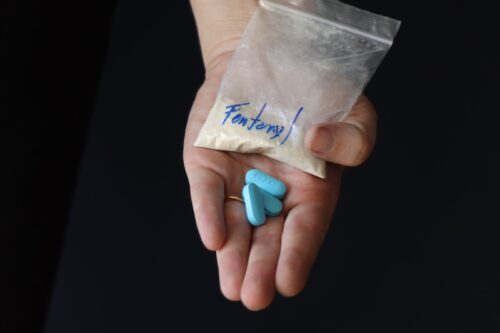

Life is not easy for the transgendered, at any age, because they deal with significant discrimination and stigma, which leads to a high prevalence of psychosocial problems. Transgender people have a particularly high likelihood of using drugs, alcohol, or smoking as a way to cope with discrimination. They are at increased risk of being victims of violence (including homicide) and suicide. For example, one study noted a 41% lifetime suicide attempt rate, compared to 1.6% in the general population (Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey 2011; http://bit.ly/1teXC7Y).

In addition, transgender people, particularly those of color and of low income, encounter significant discrimination in healthcare settings. One study found 19% reported being denied healthcare by a provider because of their gender identity, and 28% reported verbal harassment in a medical setting (Injustice at Every Turn, op.cit).

Treating Transgender Teens

The most common psychiatric issue that you will see in transgender teens is “gender dysphoria.” This is defined in DSM-5 as “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, of at least six month’s duration,” in addition to the usual stipulation of “clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning” (American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Addition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Making Progress in Diagnosis

The change in definition from DSM-IV’s Gender Identity Disorder (GID) to the DSM-5’s Gender Dysphoria was a compromise, as many in the transgender community did not want any diagnosis in DSM-5, in the same way homosexuality was dropped as a diagnosis in DSM-III. Others wanted to keep a diagnosis, as psychiatrists are currently gatekeepers for transition surgery and a diagnosis is necessary for billing and insurance reimbursement.

In DSM-IV, GID was in the chapter of sexual disorders, which included sexual dysfunctions and paraphilias. Besides relabeling from a disorder to a less stigmatizing dysphoria, Gender Dysphoria is also now in a separate chapter in DSM-5.

There are two diagnoses: Gender Dysphoria in Children (code 302.6) and Gender Dysphoria in Adolescents and Adults (code 302.85). Both diagnoses require “a marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, of at least six month’s duration manifested by criteria (six of eight for children, two of six for adolescents/adults), and clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning” (American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Addition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

According to this definition, not every transgender person meets criteria to qualify for a gender dysphoria diagnosis.

Gender dysphoria is often caused by the teen’s struggle with gender identity and social difficulties such as the lack of acceptance from their peers.

A good approach to working with these teens is to start by meeting with the youth individually, which often entails helping him or her cope with the coming out process. Only later is the family involved, because the teen must be emotionally prepared to discuss the issue with family and only when it is safe to do so. Parental acceptance is its own process, often requiring family therapy. This is a crucial part of treatment, since being rejected by parents increases the risk of attempted suicide, depression, use of illegal drugs, and unprotected sex (Ryan C et al, Pediatrics 2009;123(1):346–352). I will generally tell parents directly that family acceptance is one of the best “treatments” for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) teens.

In working directly with adolescents, I emphasize that I accept their gender identity. It’s important that teachers and peers refer to them by their preferred name and pronouns, and that they understand and accept that some teens may associate a gay identity with taking on some gender atypical behaviors. For example, they might experiment with cross-dressing or may take on an opposite gender name.

In addition to discussing social adjustment issues, you should also ask your patient whether they use hormones or would like to use them. Very few physicians are willing to provide cross-gender hormones or puberty-suppressing hormones, even if a psychiatrist is part of the treatment team. You may need to be your patients advocate to find a physician willing to provide hormone treatment. It is generally accepted that the earlier the transition, before development of secondary sex characteristics, the higher the chances of a successful gender transition, leading to a better quality of life. Teens who cannot find a doctor to prescribe hormones may access street hormones, with the risk of unclean needles (HIV, hepatitis) and inappropriate hormones/dosages.

Defining Gender Terms

Gender identity: a person’s internal sense of being male, female, or something else

Gender expression: the way a person expresses their sense of gender identity (through hair, clothes, etc.)

Gender non-conforming/variant: a person whose gender expression differs from how their family, culture, or society expects

Transgender: a person who feels that their gender identity does not match the gender assigned at birth (also: male to female (MtF), female to male (FtM), transman, transwoman)

Sexual orientation: a person’s attraction to others, usually classified as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual

Cisgender: Someone who identifies with the gender they were assigned at birth

Special Considerations in Treating Children

Although prepubertal children with gender dysphoria may show gender atypical behavior ‘from birth’, they often don’t present for treatment until they begin school due to social conflict. Although parents vary in their willingness to allow their children to explore gender variant behavior, the issue often doesn’t escalate until the child expresses him or herself in public, such as in school. Families may come to treatment when parents either cannot tolerate or don’t know how to approach the issue, or when the child begins to have conflicts with school peers, including bullying. Many of these children present with anxiety and depression that require treatment.

Treatment of gender dysphoria in prepubertal children is controversial. Hormone treatments can lead to irreversible changes. There is no consensus within the medical community on how to make such treatment decisions.

Medical Treatment Options for Transitioning Gender

Transitioning to another gender is generally separated into three phases: reversible, partially reversible, and irreversible.

Reversible changes can be implemented at any age and include adoption of preferred gender hairstyles, clothing, play, and name. By puberty, children can be given puberty suppressing hormones so they can delay further intervention until they are more capable of providing proper assent/consent (Olson J et al, Arch Ped Adolesc Med 2011;165(2):171–176).

Partially reversible treatments consist of providing cross-gender hormones. Current guidelines suggest age 16 as generally the most appropriate age to begin this in order to bypass development of the secondary sexual characteristics of the natal gender, which affect voice, height, facial hair growth, and breast development. Providing estradiol will induce irreversible breast development, while testosterone will induce irreversible clitoral enlargement and a drop in the voice (Olson J et al, op.cit).

The irreversible phase consists of the multiple surgical procedures used to create a more gender congruent appearance. Many transgender people do not have genital surgery for reasons that may include the expense, concern about sexual function/satisfaction, the belief that genitals do not define identity, or comfort in not being in a gender binary (ie, third gender, androgynous, gender queer, nongendered, etc).

There are currently three approaches to treatment of these children: corrective, supportive, and affirmative (Olson J et al, Arch Ped Adolesc Med 2011;165(2):171–176).

Corrective treatment. Since 1984, the corrective approach has been the standard clinical approach and most researched, using strategies that aim to align gender identity with biological sex. However, many experts express concern over the harm done to youth by invalidating their sense of self and note that this approach is “unscientific, unethical, and misguided, comparable to reparative therapy for homosexuality” (Drescher J, LGBT Health 2014;1(1):10–14).

Supportive therapy takes a ‘wait and see’ approach and does not focus on gender specifically, but may focus on anxiety or depression, and helping families protect their children from bullying by working with the school system. You neither validate nor invalidate the patient’s expressed gender identity. You simply work with the negative consequences as they experience them.

In the affirmative approach, you support the child and encourage active exploration of gender identity. You talk to the parents about the appropriateness of gender transition in some children. Over the past several years there have been more first-hand accounts of parents supporting their young gender variant children, advocating that their child be allowed to attend school with their chosen gender identity and name, beginning as early as elementary school (Gulli C. What Happens When Your Son Tells You He’s Really a Girl? MacLean’s January 14, 2013 [http://bit.ly/1nLZekd]). Sometimes this means needing to move to a new school/neighborhood/state as the child ends one school year in one gender and enters the new school year transitioned. Critics of this approach believe supporting gender transition in childhood can inappropriately encourage young people to persist in efforts to change genders (Drescher J, op.cit).

It is difficult to know what is the “right” approach for these children, and you have to judge each case on its own merits, being aware that you may have your own biases. For example, which is the better outcome: to be a happy transgender adult or to be a gay or heterosexual cisgender adult who may have lifelong issues with gender identity?

In the absence of scientific consensus, my approach is to pay attention to the extremes. I have seen a few cases where parents are strongly opposed to raising a child who may become a transgender or homosexual. In these cases, my role is to help the parents become more accepting of the different possible outcomes, providing them with resources to broaden their viewpoint. PFLAG [Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays] is one resource that provides support to families (http://community.pflag.org/). At the other extreme, parents may be too many steps ahead of their child regarding gender transition. In order to adjust to a new gender, some parents may choose to change the environment so the child presents as a new student in the preferred gender, as opposed to transitioning in the same environment. New peers then don’t know that this was someone of an opposite gender previously. However, several studies show moving/changing schools can be traumatic, especially for vulnerable children. In these cases, I may encourage the parents to slow down the transitioning process, allowing the child to take more of a lead.

Ultimately, the most crucial message you can give parents is that these are their children, they are special and unique, and they deserve to live authentic and happy lives.

KEYWORDS child-psychiatry gender_

Issue Date: September 1, 2014

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)