Home » Brain Development Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Drugs and Alcohol

Brain Development Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Drugs and Alcohol

February 1, 2014

From The Carlat Child Psychiatry Report

Georgia Gaveras, DO

Every day in the United States, about 650 babies are born that have been exposed to illicit drugs in the prenatal period (Keegan K et al, J Addict Dis 2010;29(2):175–191). The number would be even larger if we include women who continue to smoke cigarettes, drink alcohol, and abuse prescription drugs during pregnancy.

Figures are alarming when we look into already at-risk populations such as adolescent and young adult mothers (Williamson et al, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91(4):F291–292). According to results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), among pregnant women between the ages of 15 and 44, 8.5% reported current alcohol use, 15.9% reported smoking tobacco in the previous month, and 5.9% were current illicit drug users (http://1.usa.gov/1bJcQvG).

Often these babies end up as children in our practices. We already have the task of teasing out the complicated interplay between nature and nurture when approaching their psychiatric disorders. But many of them have a handful of developmental and learning problems, too.

Isolating the effects of a single substance of abuse on brain development can prove challenging. Prenatal and postnatal factors that usually accompany addiction in the mother often exacerbate the risk for poor developmental outcomes (Cone-Wesson B, J Commun Disord. 2005;38(4):279–302). Many of these women live in poverty, with poor prenatal care, malnutrition and usually use more than one drug. In addition, paternal substance use and, in the case of alcohol, intergenerational maternal alcoholism can add to the insult.

The degree to which a drug affects a fetus is generally dose dependent and can vary depending in the stage of development it was used. Here, we’ll explore some of the most common drugs and their effects on babies’ brains.

Tobacco

Close to one in six pregnant women in the US report having smoked cigarettes in the previous month (NSDUH op.cit). Cigarette smoking, among other things, causes impaired oxygen exchange into the placenta (Keegan K et al, J Addict Dis 2010;29(2):175–191).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study looked into the effects of cigarette smoking and marijuana prenatally on neurobehavior in a low-risk middle class population. Newborn babies of smokers were less responsive to sound and had a harder time adjusting to new noises—skills that are important parts of auditory processing.

As they grew (12 months to 24 months), they showed lower auditory processing and cognitive scores, which translate to poor language development in early childhood (age two to six). These deficits continued into the school years (Fried PA, Arch Toxicol Suppl 1995;17:233–260; Morris CV et al, Eur J Neurosci 2011;34(10):1574–1578).

The children of women who smoke during pregnancy score lower in global intelligence scores relating to verbal and auditory functioning. In addition, these children tend to be more impulsive, oppositional, and have lower working memory scores than their counterparts.

Cannabis

Marijuana is by far the illicit drug most commonly abused during pregnancy (Jutras-Aswad D, Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;259(7):395–412). Cannabis readily crosses the placenta and has been found to be associated with fetal distress, low birth weight, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, including higher incidence of psychiatric disorders. Cannabis appears to interact with the finely tuned system of endocannabinoids that regulate brain development during the prenatal period (Morris CV et al, Eur J Neurosci 2011;34(10):1574–1578).

During the first week of life, newborns exposed to marijuana in the womb show mild withdrawal symptoms and increased startle response. Some babies have poor developmental outcomes in the first six months, but soon catch up. However, by age three these children show impaired verbal, abstract visual, and quantitative reasoning skills, and at four show diminished verbal ability and memory.

By age six, children exposed to cannabis in utero start showing poor executive functioning, with deficits in attention and planning and increased impulsivity and hyperactivity, which persist into early adulthood. School-aged children show impaired visual problem solving and disorganized speech (Fried PA, Arch Toxicol Suppl 1995;17:233–260).

Alcohol

Close to 9% of pregnant women report current alcohol use, of which 2.7% report binge drinking (four or more drinks per occasion), and 0.3% reported heavy alcohol use (drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of five or more days in the past 30 days) (NSDUH op.cit). While heavy alcohol use and binge drinking have been clearly associated with detrimental effects on the fetus, it is still controversial if low to moderate alcohol consumption has any impact on neurodevelopment (Gray R et al, Addiction 2009;104(8):1270–1273).

Alcohol alters the fine dance of signals that set development, causing a wide range of consequences that are collectively known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and can be found in 2% to 5% of younger school children (May PA et al, Dev Disabil Res Rev 2009;15(3):176–192).

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), classified as a FASD, is recognized in 0.5 to 3 in 1,000 births in the US and is one of the leading causes of intellectual disability (Cone-Wesson B, J Commun Disord 2005;38(4):279–302). It describes a triad of dysmorphic facial features, growth retardation, and central nervous system abnormalities. Children with FAS score in the mild to borderline range for IQ testing (60-85 points). Even in the absence of FAS, intelligence scores tend to be lower in children exposed to moderate to heavy alcohol use during pregnancy (Weinberg NZ, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(9):1177–1186).

Children with FASD may exhibit impairments in expressive and receptive language development including areas such as such as word articulation, naming ability, and word comprehension (Wyper KR & Rasmussen CR, J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2011;18(2):e364–e376).

Children exposed to alcohol intra utero can be found to have learning deficits in a wide range of tests. Undeniably, there is evidence for poor arithmetic skills, spatial memory and integration problems, deficits in verbal memory and attention problem-solving skills, poor grammar, difficulties with information retention and comprehension and deficits in reading. Furthermore, many children exposed to alcohol in the perinatal period demonstrate poor executive functioning, impulsive behavior, aggression, inattention, and problems with social interaction.

Cocaine

Cocaine’s effect on the fetus is two-fold. Cocaine and its metabolites have direct teratogenic effects by crossing the placenta. In addition, maternal effect on cardiac and autonomic systems cause indirect consequences to the baby (Cone-Wesson B, J Commun Disord 2005;38(4):279–302).

The actual prevalence of prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) is uncertain and almost always associated with use of other illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco, and demographic factors. Babies exposed to cocaine are shorter, lighter, have smaller heads, and are likely to be born premature (Lambert BL and Bauer CR, J Perinatol 2012;32(11):819–828).

Although PCE has been associated with global lower intelligence scores, it is accepted that this is more likely related to risk factors such as poverty, low caregiver intelligence, inner-city environments, prematurity and low birth weights. The same can be said for school performance, indicating that for cocaine-exposed babies the environment where they grow can have the most negative impact on their development (Hurt H et al, Neurotoxicol Teratol 2005;27(2):203–211).

Toddlers exposed to cocaine in utero have lower language scores, which persist into elementary school, but appear to improve as children age and reach adolescence. Executive functioning impairment and difficulties regulating behavior are also impaired in PCE individuals.

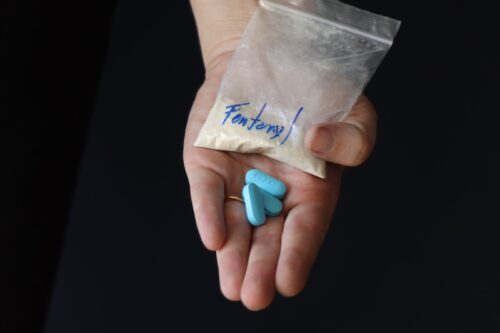

Opiates

There is little quality evidence on the effect of opiates in utero. Few studies have looked into heroin abusing mothers; but, as with cocaine, demographic factors, paternal drug use, and other comorbid substances collectively have a cumulative negative impact on the baby (Irner TB, Child Neuropsychol 2012;18(6):521–49).

ADHD-like symptoms have been described in babies exposed to opiates, but prevalence is directly related to the environment where these kids grow (Ornoy et al, Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43(10):668–675).

Data collected from mothers on methadone and buprenorphine treatment while pregnant is mixed. Some studies report normal results when compared to the general population, while others find lower scores on cognitive functioning (Konijnenberg C & Melinder A, Child Neuropsychol 2011;17(5):495–519). This conflicting evidence is likely related to time of exposure, dosage, and likely concomitant drug use.

CCPR’s Verdict: Children who are exposed to drugs and alcohol in the prenatal period can often have problems with impulse control, behavior, and learning. The factors contributing to these outcomes can be complicated by the child’s life outside of the womb, as well. Nonetheless, the degree of impairment and disability can be ameliorated by early detection and intervention, positive family environment, and specialized education programs.

Child PsychiatryFigures are alarming when we look into already at-risk populations such as adolescent and young adult mothers (Williamson et al, Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2006;91(4):F291–292). According to results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), among pregnant women between the ages of 15 and 44, 8.5% reported current alcohol use, 15.9% reported smoking tobacco in the previous month, and 5.9% were current illicit drug users (http://1.usa.gov/1bJcQvG).

Often these babies end up as children in our practices. We already have the task of teasing out the complicated interplay between nature and nurture when approaching their psychiatric disorders. But many of them have a handful of developmental and learning problems, too.

Isolating the effects of a single substance of abuse on brain development can prove challenging. Prenatal and postnatal factors that usually accompany addiction in the mother often exacerbate the risk for poor developmental outcomes (Cone-Wesson B, J Commun Disord. 2005;38(4):279–302). Many of these women live in poverty, with poor prenatal care, malnutrition and usually use more than one drug. In addition, paternal substance use and, in the case of alcohol, intergenerational maternal alcoholism can add to the insult.

The degree to which a drug affects a fetus is generally dose dependent and can vary depending in the stage of development it was used. Here, we’ll explore some of the most common drugs and their effects on babies’ brains.

Tobacco

Close to one in six pregnant women in the US report having smoked cigarettes in the previous month (NSDUH op.cit). Cigarette smoking, among other things, causes impaired oxygen exchange into the placenta (Keegan K et al, J Addict Dis 2010;29(2):175–191).

The Ottawa Prenatal Prospective Study looked into the effects of cigarette smoking and marijuana prenatally on neurobehavior in a low-risk middle class population. Newborn babies of smokers were less responsive to sound and had a harder time adjusting to new noises—skills that are important parts of auditory processing.

As they grew (12 months to 24 months), they showed lower auditory processing and cognitive scores, which translate to poor language development in early childhood (age two to six). These deficits continued into the school years (Fried PA, Arch Toxicol Suppl 1995;17:233–260; Morris CV et al, Eur J Neurosci 2011;34(10):1574–1578).

The children of women who smoke during pregnancy score lower in global intelligence scores relating to verbal and auditory functioning. In addition, these children tend to be more impulsive, oppositional, and have lower working memory scores than their counterparts.

Cannabis

Marijuana is by far the illicit drug most commonly abused during pregnancy (Jutras-Aswad D, Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;259(7):395–412). Cannabis readily crosses the placenta and has been found to be associated with fetal distress, low birth weight, and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, including higher incidence of psychiatric disorders. Cannabis appears to interact with the finely tuned system of endocannabinoids that regulate brain development during the prenatal period (Morris CV et al, Eur J Neurosci 2011;34(10):1574–1578).

During the first week of life, newborns exposed to marijuana in the womb show mild withdrawal symptoms and increased startle response. Some babies have poor developmental outcomes in the first six months, but soon catch up. However, by age three these children show impaired verbal, abstract visual, and quantitative reasoning skills, and at four show diminished verbal ability and memory.

By age six, children exposed to cannabis in utero start showing poor executive functioning, with deficits in attention and planning and increased impulsivity and hyperactivity, which persist into early adulthood. School-aged children show impaired visual problem solving and disorganized speech (Fried PA, Arch Toxicol Suppl 1995;17:233–260).

Alcohol

Close to 9% of pregnant women report current alcohol use, of which 2.7% report binge drinking (four or more drinks per occasion), and 0.3% reported heavy alcohol use (drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion on each of five or more days in the past 30 days) (NSDUH op.cit). While heavy alcohol use and binge drinking have been clearly associated with detrimental effects on the fetus, it is still controversial if low to moderate alcohol consumption has any impact on neurodevelopment (Gray R et al, Addiction 2009;104(8):1270–1273).

Alcohol alters the fine dance of signals that set development, causing a wide range of consequences that are collectively known as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and can be found in 2% to 5% of younger school children (May PA et al, Dev Disabil Res Rev 2009;15(3):176–192).

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), classified as a FASD, is recognized in 0.5 to 3 in 1,000 births in the US and is one of the leading causes of intellectual disability (Cone-Wesson B, J Commun Disord 2005;38(4):279–302). It describes a triad of dysmorphic facial features, growth retardation, and central nervous system abnormalities. Children with FAS score in the mild to borderline range for IQ testing (60-85 points). Even in the absence of FAS, intelligence scores tend to be lower in children exposed to moderate to heavy alcohol use during pregnancy (Weinberg NZ, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(9):1177–1186).

Children with FASD may exhibit impairments in expressive and receptive language development including areas such as such as word articulation, naming ability, and word comprehension (Wyper KR & Rasmussen CR, J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2011;18(2):e364–e376).

Children exposed to alcohol intra utero can be found to have learning deficits in a wide range of tests. Undeniably, there is evidence for poor arithmetic skills, spatial memory and integration problems, deficits in verbal memory and attention problem-solving skills, poor grammar, difficulties with information retention and comprehension and deficits in reading. Furthermore, many children exposed to alcohol in the perinatal period demonstrate poor executive functioning, impulsive behavior, aggression, inattention, and problems with social interaction.

Cocaine

Cocaine’s effect on the fetus is two-fold. Cocaine and its metabolites have direct teratogenic effects by crossing the placenta. In addition, maternal effect on cardiac and autonomic systems cause indirect consequences to the baby (Cone-Wesson B, J Commun Disord 2005;38(4):279–302).

The actual prevalence of prenatal cocaine exposure (PCE) is uncertain and almost always associated with use of other illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco, and demographic factors. Babies exposed to cocaine are shorter, lighter, have smaller heads, and are likely to be born premature (Lambert BL and Bauer CR, J Perinatol 2012;32(11):819–828).

Although PCE has been associated with global lower intelligence scores, it is accepted that this is more likely related to risk factors such as poverty, low caregiver intelligence, inner-city environments, prematurity and low birth weights. The same can be said for school performance, indicating that for cocaine-exposed babies the environment where they grow can have the most negative impact on their development (Hurt H et al, Neurotoxicol Teratol 2005;27(2):203–211).

Toddlers exposed to cocaine in utero have lower language scores, which persist into elementary school, but appear to improve as children age and reach adolescence. Executive functioning impairment and difficulties regulating behavior are also impaired in PCE individuals.

Opiates

There is little quality evidence on the effect of opiates in utero. Few studies have looked into heroin abusing mothers; but, as with cocaine, demographic factors, paternal drug use, and other comorbid substances collectively have a cumulative negative impact on the baby (Irner TB, Child Neuropsychol 2012;18(6):521–49).

ADHD-like symptoms have been described in babies exposed to opiates, but prevalence is directly related to the environment where these kids grow (Ornoy et al, Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43(10):668–675).

Data collected from mothers on methadone and buprenorphine treatment while pregnant is mixed. Some studies report normal results when compared to the general population, while others find lower scores on cognitive functioning (Konijnenberg C & Melinder A, Child Neuropsychol 2011;17(5):495–519). This conflicting evidence is likely related to time of exposure, dosage, and likely concomitant drug use.

CCPR’s Verdict: Children who are exposed to drugs and alcohol in the prenatal period can often have problems with impulse control, behavior, and learning. The factors contributing to these outcomes can be complicated by the child’s life outside of the womb, as well. Nonetheless, the degree of impairment and disability can be ameliorated by early detection and intervention, positive family environment, and specialized education programs.

KEYWORDS child-psychiatry learning_

Issue Date: February 1, 2014

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)