Learning Objectives

After the webinar, clinicians should:

1. Understand categorical and dimensional approaches to diagnosing borderline personality

2. Describe core principles of management

3. Summarize research findings on psychiatric treatment

Transcript edited for clarity

Hello, I'm Jason Mallo, a psychiatrist in Portland, Maine, and the Division Director at Maine Medical Center, Adult Outpatient Psychiatry. In this webinar, I'll discuss the diagnosis and management of borderline personality disorder (BPD). I have no conflicts of interest.

One question at hand for this presentation is how do you diagnose BPD? I'm going to review two diagnostic models, the categorical and dimensional. There are others. For instance, we've always had “astrology.” But these are the two major players right now. Then I will review core principles of management, which are based on a contemporary evidence base.

A take-home message for management is that you do not need to be an expert in borderline personality to help your patients. And I will introduce tactics that can be applied in different treatment settings.

Borderline Personality Disorder: The Basics

Key points

- Lifetime prevalence is 6%

- Accounts for 20% of psychiatric inpatients and 10% of outpatients

- Roughly equal F/M ratio

- Up to 70% attempt and 10% die by suicide

- Too few specialists to care for these patients

BPD is a common disorder. It affects 6% of all Americans. That is something like 19 million Americans. For those of you who work with patients that have a history of psychiatric hospitalization, you can expect that 1 out of 5 have the disorder. And believe it or not, in recent epidemiologic studies, the female to male ratio is roughly equal. This may not be what you learned in training or see in your practice.

Females tend do tend to present more often for care, but they may also be diagnosed in a biased fashion. The bias can go both ways, however, as men with BPD pathology may more often be seen as antisocial or narcissistic. Suicide attempts as well as nonsuicidal self-injury are very common. A total of 10% actually die by suicide. This is a very lethal disorder. Probably the most important point here is that there are way too few providers available to care for these patients. This is a public health challenge and therefore an important topic to know about

DSM’s Categorical Taxonomy of BPD

BPD first showed up in the DSM in 1980, and at the time, Robert Spitzer led a revision of the DSM that incorporated a categorical taxonomy. This seemed to channel Emil Kraepelin's classification system.

The criteria for BPD have not changed much since their introduction. The nine DSM-5 criteria are listed here and divided into four domains: Unstable emotions, impulsive behaviors, inaccurate perceptions, and unstable relationships. To be diagnosed, a person must have at least five of nine criteria, and it can be any five across these domains.

Symptom domains and criteria:

- Unstable emotional responses: mood instability, inappropriate anger, and feelings of emptiness

- Impulsive behaviors: self-damaging acts and suicidal or nonsuicidal self-harm

- Inaccurate perceptions: identity disturbance and transient paranoia or dissociation

- Unstable relationships: abandonment issues and interpersonal difficulty

One of the things I like about this model is there's a simplicity to it. To differentiate BPD from bipolar disorder, it is essential to identify the course of the patient's mood instability. Minutes to hours of unstable emotional responses, often accompanied by environmental triggers, is characteristic of BPD. Often there is some form of interpersonal distress (with BPD). Whereas someone being in an emotional state that's uncharacteristic of their baseline for multiple days to weeks is a sign of bipolar disorder.

In BPD, you can see suicidal thoughts and acts and nonsuicidal self-injury, such as cutting, as well as impulsive behaviors that are often geared towards reducing heightened, uncomfortable emotions.

Identity disturbance may present as fluctuating self-perceptions. A patient may present as confident one appointment and utterly worthless the next. They can also present with transient paranoia about others or the world, as well as dissociation, which is not fixed. These symptoms also are response to perceived interpersonal and environmental stress.

Critique of the Categorical Model

Key points

- Limits of our language

- Disorders are present or absent, without concept of wellness

- Heterogeneity within and overlap between disorders

- Boundary between normal and abnormal seems arbitrary

Now, here's some critique about the categorical model. There are limitations that have been borne out of the language of the DSM. For instance, with patients who have BPD, you may have heard one say, “My mania was really acting up yesterday.” The language of the DSM has been adopted and adapted by the general public. People do not come into treatment so much anymore requesting help for understanding their mood and relationships.

Providers have also been limited by the language of the DSM. For patients that are diagnosed with personality disorder, the most common diagnosis on the books is personality disorder NOS or unspecified, which is really not that informative. One explanation for this is our patients do not easily fit into the categorical model.

Another critique is disorders in the DSM are either present or absent. A patient has a disorder or doesn't, and the DSM does not offer us a concept of what wellness is.

There's heterogeneity within and overlap between disorders. For instance, there are 256 different ways someone can meet the DSM criteria for BPD.

Lastly, the boundary between normal and abnormal seems to be pulled out of a hat. And it tends to identify only the most severe forms of personality pathology.

Dimensional Model for Personality Organization

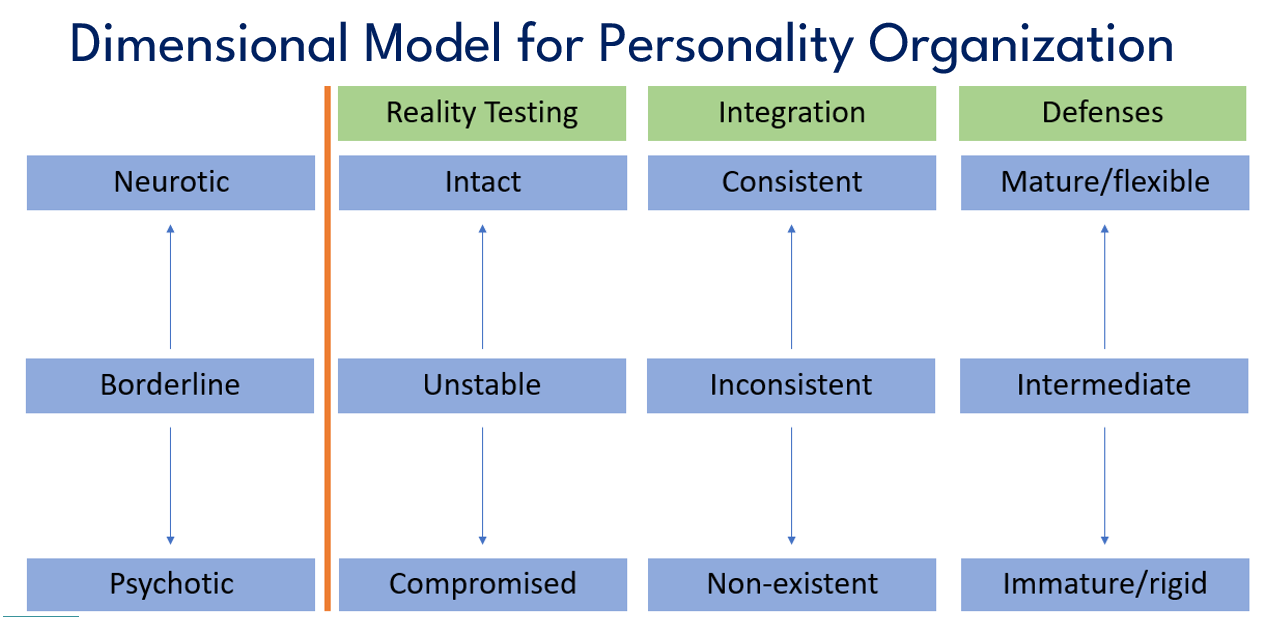

The dimensional model is another way to understand personality functioning. Many years ago, Otto Kernberg proposed personality could be understood on a spectrum from more neurotic to more psychotic, with borderline in the middle. This is not borderline personality disorder per se, but what he referred to as borderline personality organization, which includes BPD, and I think it is also useful in understanding BPD.

Under enough stress or with enough support, individuals can move up and down the neurotic psychotic spectrum at any given point in time. However, most of the time, individuals exist and that is they have a pattern of thinking, feeling, and behaving that exists in a particular zone.

Now, subcategories of the spectrum include reality testing, integration, and defense mechanisms. With reality testing at the neurotic end, reality testing is intact. At the borderline level, it is unstable and episodically compromised, and at the psychotic level, there are enduring breaks with reality.

Integration refers to the degree to which an individual has a coherent, complete, and complex sense of self and others. At the neurotic level, consistent is consistent with someone being able to accurately recognize positive and negative aspects of self and other. There's an ability to be ambivalent and to experience guilt about hurting others. For instance, someone at this end of the spectrum could experience symptoms of depression and anxiety, but their sense of who they are does not totally go to pieces when they're faced with a challenge. They may feel discouraged and frustrated with bad news, but not totally shameful or worthless. And they can take some accountability for their circumstances as well.

At the borderline level, integration is chameleon-like and it's inconsistent over time. It can fluctuate and it depends on the situation. In relationships, there is less of a concern for others, and one's own needs being met can dominate. Their world is filled with more victims, rescuers, and persecutors. But these characteristics can change over time. And in a world of good or bad, there's less room for guilt. At this level patients have difficulty accurately assessing themselves and others in depth over time, especially when stressed. They struggle to commit to a life direction and stick with it and to maintain deep and enduring relationships.

In psychosis, the boundary between self and other is broken more consistently. Patients have inaccurate experiences of self and others that persist.

For defense mechanisms, at the neurotic end, they are mature and flexible. They accommodate to reality and social demands. They function well with others. Think altruism, humor, and sublimation. Also in this area, but maybe more intermediate are rationalization and reaction formation, like when a patient is overly complimentary, but really, they're quite frustrated with you.

At the intermediate level, we get splitting, idealization, devaluation, projective identification, and acting out. The intermediate defenses are consistent with what we see in BPD. And as we move further down the spectrum, we get denial, delusional projection, and extreme or delusional somatization. And these sort of defenses rearrange reality to accommodate to the individual and as a result, they do not fit in well with functioning in society.

Critique of the Dimensional Model

Key points:

- Difficult to grasp

- Absence of clear boundary for normality

- Lacks guidance on treatment

- Overlooks personality based on themes with 2-dimensional poles

The dimensional model is not perfect. It's hard to conceptualize. It's also hard to imagine applying it in a modern-day clinical practice and across different treatment settings, especially those where patients are seen briefly or there are pressures to medicalize psychiatric problems. Unlike the categorical model, which is concrete, the dimensional one is abstract, and it lacks a clear boundary for what is normal versus pathologic. It lacks guidance on treatment recommendations, and more research is needed in this area.

Lastly, this model overlooks how personality may be conceptualized as themes with two dimensional poles represented. For instance, for the borderline patient, they can be social and seek connection with others, but then again be secretive, shut off, and not share the entire picture. They can be perceived as manipulative interpersonally. But they can also be so warm and self-denying; and they can appear so unhappy with you and disorganized and yet also be so loyal and rarely, if ever, miss a session.

An Integrated Approach to Diagnosis

Key points:

- Review the diagnostic criteria with your patient, but don’t stop there

- DSM5’s Alternative Model:

- Criterion A: level of personality functioning

- Criterion B: personality traits

I think the best approach to diagnosis is an integrated approach and one that involves the patient in the diagnostic process. For those who you suspect have BPD, review the DSM criteria with them. I would go through each of the nine, which really doesn't take that long. It's probably less than 10 minutes.

And if they're squeamish about the diagnosis, maybe just review the criteria first before getting into the name. Don't stop with the criteria, however; develop an individualized biopsychosocial formulation that includes patient weaknesses and strengths. And to do that, you can refer to the dimensional model that I just reviewed. It may be useful to point out that BPD patients at times exhibit clear reality testing and that they do use healthier defenses at times. These are things that can be pointed out to bolster their treatment.

When you feel you have a working diagnosis and formulation, I'd share that with your patient. For me, by and large, this goes well, and patients appreciate the thoughtful approach. Most patients are accepting of the diagnosis when it's presented this way, and with some education. They're interested and they express relief. Of course, there are going to be instances though in which patients struggle with the diagnosis and they don't want to hear anything about it.

This could be related to interpersonal issues with control and power. Also, it often has to do with stigma and misinformation that exists about BPD. In those cases, you might need to hedge your bets and say something like, “I think this disorder applies, but let's table it for now.” And then with more time, education, patience, and at the patient's pace, they can come around.

Interestingly, the DSM-5 includes an alternative model for diagnosing personality disorder. And I think it's worth checking out because I foresee it will become the leading diagnostic model in the future. It's an amalgam of categorical and dimensional approaches. For instance, Criterion A, Level of Personality Functioning, has to do with the degree to which someone's sense of self and others is well integrated. This criterion reads as if it was taken directly from the dimensional model that I reviewed. Criterion B gets at what someone's individual personality is like, their personality traits, and it reads like categorical symptoms. And it includes emotional lability, hostility, impulsivity, and separation insecurity.

Core Principles of Management

Now I'm going to switch gears and talk about managing BPD. Some of you may be thinking, I can't treat BPD. I haven't trained in dialectical behavior therapy. Well, I'm here to tell you that you can. And I'm going to review five core principles of management that you can employ with your patients.

- Offer diagnostic disclosure

- Validate distress, but don’t give into demands

- Anticipate interpersonal hypersensitivity

- Prescribe conservatively

- Encourage work over love

These core principles are taken from good psychiatric management (GPM), and the work of John Gunderson, Lois Choi-Kain, and others. They are practical and can be applied in any setting by a wide range of providers.

Diagnostic Disclosure

Key points

- Diminishes sense of alienation

- Anchors expectations about course and treatment

- Fosters alliance

- Medicalizes their experience and decreases blame

- Prepares clinicians for countertransference

Now, I've already spoken about how to approach diagnosis, but it's also important to point out that diagnostic disclosure is a useful therapeutic tool in and of itself. For instance, it can reduce a patient's sense of being alone. This is a real disorder that others struggle with. It anchors expectations about course and treatment. Patients with this disorder can expect that over time, their condition is going to improve. BPD is a treatable illness. And at the 10-year mark, about 80% of patients no longer meet the full criteria for the disorder.

Identifying a patient has BPD can reduce the risk of unnecessary treatments like polypharmacy. Diagnosing helps foster a working alliance around a shared understanding of a patient's disorder. It helps reassure them that you can make sense of what they're struggling with. It also medicalizes their experience and decreases self-blame and parent blame. It is no one person's fault that they have this.

Lastly, diagnostic disclosure helps warn clinicians about a patient that will likely stir up strong emotions. Keeping that in mind over time can be useful in avoiding our feelings getting in the way of a patient's treatment.

Validate Distress, But Don’t Give In to Demands

Key points

- Acknowledge the patient’s experience

- Remain calm and nonreactive; tolerate the patient’s anger empathically

- Hold the patient accountable

- Schedule consistent visits and set goals in between visits

When a patient is distressed, they can come across as angry, emotional, and tearful. You want to first validate their experience. This is not validating their emotions as being based on truth or fact, but rather recognizing they're upset and in distress. It is reflecting back to them that you know they're upset and that you're curious to explore what is bothering them. This alone can tone down the severity of their emotional state.

Validating their distress does not mean you have to give in to their demands, especially demands that are not appropriate for their condition or outside of your usual practice. For example, in an outpatient setting, you can acknowledge their distress but should not be calling you in the middle of the night with every crisis. You can't always be available, and there are crisis services if needed. Then, stick with the limits that you set and hold the patient accountable for sticking to them as well.

Another tip is to schedule frequent visits that are brief, consistent, and predictable. This can help avoid reinforcing the link between crisis and clinical care. Part of your job is not getting swept up in the tornado and always prioritizing urgent medical needs.

Interpersonal Hypersensitivity

- Stages: connected <-> threatened <-> aloneness <-> despair

- Responding to hypersensitivity:

- Be curious, inquire about how you contributed, and collaborate

- Evaluate safety risk

Interpersonal hypersensitivity is a key concept in good psychiatric management, and I recommend educating all your patients about it. There are different stages in this model, and these stages relate to how an individual is feeling internally in relation to others.

Patients can feel connected, threatened, alone, or in despair. When connected, patients typically are doing relatively well. However, they may idealize others or depend heavily on others. They may also be rejection sensitive. And when interpersonal stress arises, the boat can be rocked, and they can end up moving into the next stage.

When threatened, patients may devalue others or themselves; have intense emotions; can be self-injurious; and are typically help-seeking. This commonly happens in the context of patients feeling rejected. For example, you are five minutes late to start their appointment, and you can tell they're clearly angry. In that instance, don't get defensive and offer explanations. Instead, recognize they're feeling angry, and inquire what contributed. That recognition and non-defensive curiosity can help them feel supported and connected again.

If they don't find that kind of support, they may move on to the next stage in this model, which is alone. In the aloneness stage, things get worse. Patients might dissociate, exhibit paranoia, and are commonly help-rejecting. Sometimes leaning into supporting them further, offering them a sooner appointment, for instance, can help here.

If they go further into feeling disconnected, they can go into despair, where things get really dangerous. Nothing feels good to them, and they can feel very suicidal.

You have to take notions of self-harm and suicidality seriously. However, evaluating their safety risk does not mean you have to hospitalize them. Try to differentiate between nonsuicidal self-harm and suicidal. Cutting does not necessarily mean someone wants to end their life. If they are suicidal, inquire what has happened that brought on these feelings and these thoughts. This can commonly be addressed in an appointment, and when you address their risk and what contributed, you'll find their suicidality tends to lessen.

Their risk can then be decreased further by increasing support at their home or removing dangerous means of hurting themselves. At this time, I would remind them of the hypersensitivity model. And be explicit that feeling rejected or no longer connected contributed. You should inquire about how you can help support them to feel more connected.

I would introduce the stages of interpersonal hypersensitivity early in treatment. Ask your patient if this is a pattern they recognize. Talk with them about what it is like. Help them start to recognize this process and make sense of their own interpersonal experiences. It is an important part of treatment and treating BPD.

Prescribe Conservatively

- No medication is FDA approved

- Maintain realistic expectations:

- No medication is uniformly or dramatically helpful

- Polypharmacy is associated with worse outcomes

- Benzodiazepines are generally contraindicated

- Don’t continue a medication if it is not helping

There are no medications FDA approved for treating borderline personality disorder and the notion that a patient can be prescribed a medication and recover is a fantasy.

While no medication is uniformly or dramatically helpful, they can reduce symptoms. And if you were to pick one, you might pick an atypical antipsychotic. For BPD, they have been shown to reduce mood swings, anxiety, anger, and impulsivity. Their side effect burden, however, comes with a price tag, including metabolic syndrome and EPS (extrapyramidal symptoms). Compared to atypicals, antidepressants are less helpful, but they are safer, and they may be categorized as somewhat helpful.

Mood stabilizers are helpful for symptoms of anger and impulsivity in BPD, but not as much for mood swings, depression, or anxiety, and each of them comes along with a risk of organ toxicity. Which organ depends on the mood stabilizer that you pick. Benzodiazepines are a group that are contraindicated, and the reason is that they can increase disinhibition and lead to more impulsivity and interpersonal problems. I do prescribe them, but I think there is good reason to avoid them, or only use them in the short term.

Lastly, it is not unheard of that patients with BPD end up on multiple medications. Polypharmacy is typically a sign of poor prognosis, and it risks side effects and med-med interactions. With BPD, it is especially important to identify up front what you are prescribing a medication for, what symptoms, and if it's not helping your patient over time, I would discontinue it.

Encourage Work > Love

Key points

- Patients can be preoccupied with finding love, but BPD is sensitive to interpersonal stressors

- Work provides structure and meaningful experiences

- Skills developed in psychotherapy can be mastered in vivo

The last principle I want to talk about is encouraging work. Some patients with BPD are preoccupied with finding love. The snag is relationships, especially intimate ones, can be a source of distress and a setup for bad outcomes. Therefore, I would encourage work over finding love. Lacking work is a pivotal reason that some patients with BPD do not get better. Work provides structure and routine, which can support social functioning, self-esteem, and symptom reduction.

Skills developed in therapy can be practiced on the job. “Getting a life” is an essential ingredient for your patients getting better.

Carlat Take

Key points

- Verge of paradigm shift for diagnosing BPD and other PDs

- An integrated categorical and dimensional approach offers simplicity and complexity

- Most patients can be managed effectively with core principles from GPM

- If needed, more intensive treatments include DBT, MBT, TFP, and ST*

For years, the DSM's categorical model for diagnosing BPD has been the dominant model. The introduction of the alternative model of personality disorder in the DSM 5, I believe, speaks to a paradigm shift that is afoot. An integrated approach—such as recognition of a patient's strengths and weaknesses—offers greater depth.

There are, of course, specialized, intensive treatments for BPD. For most patients, however, their disorder can be managed effectively with the principles of GPM that I have reviewed here, including diagnostic disclosure and education about interpersonal hypersensitivity.

When the core principles are not enough, I would consider referring your patient to one of the modalities listed at the end here. A driving factor in choosing one of these modalities is unfortunately often based on availability. However, they are all effective. And if your patient does not respond to one adequately, then I would consider referring them to another. Form of treatment.

*DBT: dialectical behavioral therapy; MBT: mentalization-based therapy; TFP: transference focused psychotherapy; ST: schema therapy

Thank you for watching this webinar.

Earn CME for watching our webinars with a Webinar CME Subscription.

REFERENCES:

Biskin RS, Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(7):303-308

Grant BF et al, J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533-545

Paris J and Zweig-Frank H, Compr Psychiatry 2001;42:482–487

American Psychiatric Association. Borderline personality disorder. In: DSM5-TR. 2022:753-758

Westen D and Arkowitz-Westen L, Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:1767-1771

Kernberg O, J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1967;15:641-685

McWilliams N and Shedler J. Personality syndromes—P Axis. In: Lingiardi V and McWilliams N, eds. Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2017:15-69

American Psychiatric Association. Alternative model for personality disorders. In DSM5-TR. 2022;881-901

Mulay AL et al, Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul 2019;6:18

Choi-Kain L and Gunderson J. Applications of Good Psychiatric Management for Borderline Personality Disorder. APA Publishing, Washington DC. 2019:169-187

Gunderson J and Links P. Handbook of Good Psychiatric Management for Borderline Personality Disorder. APA Publishing, Washington DC. 2014:13-20

Mercer D et al, J Pers Disord. 2009;23(2):156-174

Silk K and Feurino L. Psychopharmacology of personality disorders. In: The Oxford Handbook of Personality Disorder. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012:713-726

__________

The Carlat CME Institute is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. Carlat CME Institute maintains responsibility for this program and its content. Carlat CME Institute designates this enduring material educational activity for a maximum of one-half (.5) AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM. Physicians or psychologists should claim credit commensurate only with the extent of their participation in the activity.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)