Off-Label Strategies for Common Psychiatric Conditions

FDA approval is often seen as a “gold standard,” but not all approved medications are first line in their class. In this article, I’ll highlight areas where an off-label option might be preferred over those with FDA approval.

PTSD

Before reviewing medications for PTSD, it’s important to note that psychotherapy is generally considered to be the first-line treatment. When therapy and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants are compared head-to-head, therapy has greater and longer-lasting benefits in PTSD (Storm MP and Christensen KS, Dan Med J 2021;68(9):A09200643).

Two SSRI antidepressants are approved for PTSD (sertraline 50–200 mg/day and paroxetine 20–50 mg/day), but when you dig into the evidence, both of these FDA-approved options have strikes against them. Sertraline was effective in only two out of seven controlled trials, enough to get it approved, but not enough to show any benefit in meta-analyses that included the unpublished, negative trials (Hoskins M et al, Br J Psychiatry 2015;206(2):93–100). Paroxetine has enough positive trials to pass the efficacy mark, but its tolerability is poorer than other antidepressants in PTSD.

Two off-label options worth considering first line are fluoxetine (20–40 mg/day) and venlafaxine (75–225 mg/day). Both had positive results in meta-analyses and rank first line in many treatment guidelines. When all side effects (including withdrawal problems) are considered, fluoxetine is the best tolerated of the two.

For patients with prominent nightmares or nocturnal awakenings, prazosin is a good option, and some guidelines recommend it first line for these features. Prazosin also improves daytime hyperarousal, and it surpasses the antidepressants in at least one important way. Prazosin worked in both military and civilian populations, while the antidepressants worked mainly in women with civilian trauma (Bajor LA et al, Psychiatry Res 2022;317:114840). However, prazosin also has negative trials.

Prazosin has a wide dose range, and that range stretched higher in studies of men (max 25 mg/day) than women (max 12 mg/day). Start at 1 mg QHS and raise by 1–2 mg every four to seven days based on response and tolerability. Around 25% of the dose can be given in the morning after reaching a daily dose of 3–5 mg. Check blood pressure and pulse and monitor for falls during titration. If a patient is taking other antihypertensives, consult with the provider managing those and consider tapering them after titrating prazosin.

CARLAT VERDICT

PTSD benefits from a personalized approach. Start with prazosin for prominent nightmares and sleep disruption. For general symptoms, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, and paroxetine are top choices, and fluoxetine has the best tolerability.

Antidepressant Augmentation

The FDA-approved options for antidepressant augmentation are limited to antipsychotics and esketamine. The five approved antipsychotics are aripiprazole 5–15 mg/day, brexpiprazole 2–3 mg/day, cariprazine 1.5–3 mg/day, olanzapine 5–15 mg/day with fluoxetine, and quetiapine 150–300 mg/day. Risperidone (0.5–3 mg/day) also has good evidence but is not clearly better than the approved options. The folate supplement L-methylfolate (Deplin, 7.5–15 mg/day) is FDA approved as a “medical food” for antidepressant augmentation, which is a less rigorous standard than approval as a medication.

Notably absent from that list is lithium, which is only approved in bipolar disorder despite ranking first line for antidepressant augmentation in five treatment guidelines (Taylor RW et al, Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2020;23(9):587–625). Studies vary on whether lithium or the antipsychotics are more effective, but in the short term it’s fair to say that both have comparable benefits and tolerability (Vázquez GH et al, J Psychopharmacol 2021;35(8):890–900).

Lithium’s main advantage is found in long-term studies, where it reduces the risks of suicide, psychiatric hospitalizations, and depressive recurrence in both unipolar and bipolar disorders (Undurraga J et al, J Psychopharmacol 2019;33(2):167–176). Patients at risk for suicide are good candidates. Other predictors of a good response to lithium augmentation of antidepressants include severe depression, high recurrence (>3 past episodes), significant weight loss, psychomotor retardation, and a family history of bipolar disorder or of lithium response (Taylor et al, 2020).

Lithium can be added to any antidepressant, although it carries a very low risk of serotonin syndrome when used with serotonergics or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Start with 150–300 mg at night and raise by 300 mg every three to seven days toward a target dose of 900 mg QHS (or 450 mg if the patient is elderly or has drug interactions). Then wait five days and check the trough level in the morning, aiming for a serum level of 0.5–0.8 mEq/L (for the elderly, lower the target level to 0.4–0.7 mEq/L for age 60–79 years and 0.4–0.6 mEq/L for age ≥80 years).

CARLAT VERDICT

For antidepressant augmentation, the off-label lithium is a close competitor to the atypical antipsychotics and may be preferable for patients at risk for suicide.

Ketamine vs Esketamine

In 2019, the FDA approved esketamine (Spravato) for treatment-resistant depression and depression with suicidality, but some would argue they got the wrong drug.

Compared to esketamine, the unapproved ketamine was twice as likely to bring patients to response or remission, and less likely to lead to dropouts, in an analysis of 24 trials (Bahji A et al, J Affect Disord 2021;278:542–555). Ketamine contains esketamine and its mirror-image enantiomer arketamine in a 50/50 racemic mix. Since ketamine is generic, the only profitable path to FDA approval was by copyrighting and testing one of those enantiomers, which Janssen did with esketamine.

The other enantiomer, arketamine, is under development through Perception Neuroscience, and it’s this enantiomer that may explain ketamine’s superior effect. Animal data suggest arketamine is safer and more effective than esketamine, with greater antidepressant effects and lower abuse potential. Another explanation involves the mode of delivery. Ketamine is usually delivered IV, leading to greater absorption and higher plasma levels than the intranasal esketamine.

Although the available data favor ketamine over esketamine, none of this information is based on direct, head-to-head comparisons. In fairness, esketamine’s trials were designed in a way that tends to dampen effect size (ie, they were larger and more rigorous).

What about oral ketamine? This form is prescribed at some clinics as a lozenge, but it is not as strong an off-label contender as the IV form. Fewer than 10% of the ketamine trials tested the oral form. Ketamine has low bioavailability, so the oral version may not be reliably absorbed. Oral ketamine also raises the risk of diversion. Ketamine and esketamine are Schedule III controls, and the FDA requires patients to take esketamine under supervision. Practitioners would be wise to follow that same standard when using ketamine off-label.

CARLAT VERDICT

Ketamine may be more effective than esketamine. For patients who need this level of care, both are reasonable options, and the choice often comes down to pragmatics. Ketamine is less costly, but also less likely to be covered by insurers.

Autism

Although there are no FDA-approved medications for autism, two antipsychotics—aripiprazole (5–15 mg/day) and risperidone (0.5–3 mg/day)—are approved for irritability associated with autism in children (5–17 years old). Both antipsychotics improved irritability with a large effect size. They also reduced hospitalization rates. Between the two, aripiprazole was better tolerated (Fung LK et al, Pediatrics 2016;137 Suppl 2:S124–S135).

However, antipsychotics carry significant risks, particularly in children who are more vulnerable to their metabolic effects. For irritability in autism, behavioral and family therapy are first line, and antipsychotics are best reserved for short-term management of severe aggression. For less severe aggression, there are safer options with controlled-trial evidence. These include the ADHD medication clonidine (0.1–0.3 mg/day, usually delivered by transdermal patch), and two supplements: omega-3 fatty acids (600–1500 mg/day of EPA + DHA omega-3) and the glutamatergic antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC, 500–2700 mg/day) (Fung et al, 2016).

CARLAT VERDICT

No medications target the core symptoms of autism. For problematic aggression, start with psychotherapy approaches, clonidine, omega-3, or NAC. Reserve the FDA-approved antipsychotics for severe aggression where the benefits outweigh the risks.

Binge Eating Disorder

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is the sole FDA-approved agent here, with specific approval for moderate to severe binge eating disorder (BED) in adults. On the surface, there is not much to argue with. Lisdexamfetamine 50–70 mg/day brought about a meaningful difference in three large trials (Fornaro M et al, Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:1827–1836). Although patients were twice as likely to discontinue lisdexamfetamine as they were to discontinue placebo, the drug did not cause serious harm and had a reasonable safety profile in a one-year extension study.

On the other hand, amphetamines like lisdexamfetamine can worsen many of the disorders that commonly co-occur with BED, particularly bipolar, borderline, psychotic, and substance use disorders (Welch E et al, BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:163). Patients with a history of those disorders were excluded from the trials, as were those with hypertension, cardiac disease, or significant symptoms of any comorbid psychiatric disorder.

Around one in five patients with bipolar disorder have BED, particularly those with emotional reactivity, impulsivity, and atypical depression (ie, the depression that raises appetite) (Boulanger H et al, J Affect Disord 2018;225:482–488). For these patients, topiramate (150–600 mg/day) is a safer option. For patients with other comorbidities, where an antidepressant may be safe but an amphetamine ill advised, several antidepressants have evidence in BED: duloxetine (60–120 mg/day), fluoxetine (40–60 mg/day), and sertraline (100–200 mg/day) (Reas DL and Grilo CM, Expert Opin Pharmacother 2015;16(10):1463–1478). For all patients with BED, psychotherapy is worth considering first.

CARLAT VERDICT

Psychotherapy is first line for BED. The FDA-approved lisdexamfetamine is appropriate for pure BED, but a nonstimulant is often preferable for patients with major psychiatric comorbidities.

Tardive Dyskinesia

The vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors deutetrabenazine (Austedo) and valbenazine (Ingrezza) were approved for tardive dyskinesia (TD) in 2017 through the FDA’s accelerated pathway. They are an improvement over the original VMAT2 inhibitor, tetrabenazine, which carries a risk of inducing depression and suicidality.

Although these FDA-approved options are first line for TD, they come with problems that will send many to second-line options. They cost around $80,000 per year, and many do not respond to them, based on their number needed to treat of 4–7 (Solmi M et al, Drug Des Devel Ther 2018;12:1215–1238). In that case, amantadine (100–400 mg/day) and levetiracetam (Keppra, 500–3000 mg/day) are reasonable alternatives.

Amantadine is a glutamatergic medication that is approved for dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. It has been used since the early 1970s for TD and ranks just below VMAT2 inhibitors in treatment guidelines for TD, with support from three controlled trials (Artukoglu BB et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2020;81(4):19r12798). It also reduced antipsychotic weight gain in five controlled trials, where it had additional benefits in negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Zheng W et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2017;37(3):341–346). The main side effect is insomnia, although rarely it can induce hallucinations.

Levetiracetam (Keppra) is an anticonvulsant that modulates dopamine transmission. Its ability to improve dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease led to open-label studies in TD that were confirmed by a small controlled trial (Artukoglu et al, 2020). Somnolence and dizziness are its main risks, although rarely it can cause neuropsychiatric symptoms from aggression to depression. While most anticonvulsants cause cognitive dulling, levetiracetam has potential procognitive effects, and it did improve negative symptoms of schizophrenia in a controlled trial (Behdani F et al, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2022;37(4):159–165).

In some situations, it is better to switch or discontinue the antipsychotic to address TD. Clozapine does not cause TD and is a good option for patients with schizophrenia who have not responded well to two antipsychotic trials. In mood disorders, antipsychotics are often used as augmentation, and they can be tapered off in favor of relying on other therapies for prevention.

CARLAT VERDICT

The FDA-approved options for TD are first line, but their cost will steer many toward the off-label amantadine and levetiracetam.

Antipsychotic Weight Gain

The FDA has approved only one medication to reduce weight gain on antipsychotics. Lybalvi is a combination of the opioid antagonist samidorphan with olanzapine, and in my view, it is not first line.

Although samidorphan prevented weight gain, it did not make a dent in the more meaningful markers of metabolic syndrome. Metformin, in contrast, improved insulin sensitivity, fasting glucose, and triglycerides, as well as hyperprolactinemia and cognition (Zheng W et al, J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35(5):499–509; Zheng W, J Psychopharmacol 2017;31(5):625–631). Compared to Lybalvi, which was only tested in nonobese patients, metformin has support from a larger and broader body of research. APA guidelines recommend it first line for adverse effects of antipsychotics.

Metformin is well tolerated. Nausea and diarrhea are the most common side effects and improve by taking the medication with food or using the extended-release form. Very rarely, metformin can cause lactic acidosis or vitamin B12 deficiency. Its benefits are greater when started early in the course of antipsychotic therapy before weight gain gets out of control.

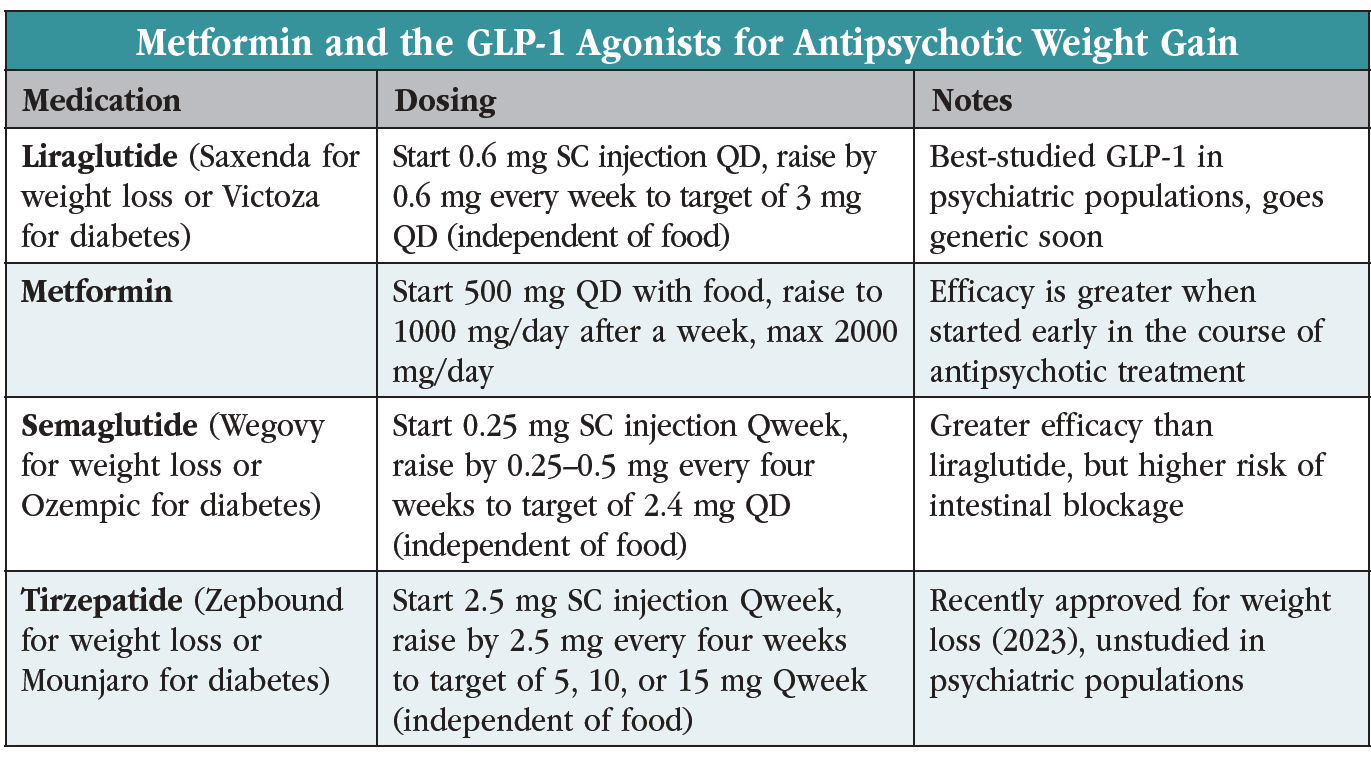

With over a dozen randomized controlled trials for antipsychotic weight gain, metformin is the best-studied agent in this area but lacks FDA approval for any kind of weight loss. Its dominance is being challenged by the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, three of which are FDA approved for weight loss in obesity (see the table “Metformin and the GLP-1 Agonists for Antipsychotic Weight Gain”). Specifically, liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide are approved for patients with a BMI ≥30 kg/m². If the patient has medical complications of obesity (eg, hypertension, type II diabetes, or dyslipidemia), a BMI ≥27 kg/m² is allowed.

Two GLP-1 agonists—liraglutide and semaglutide—have support from case series in antipsychotic weight gain, although only liraglutide has a randomized controlled trial there. After adjusting for placebo, liraglutide led to a 12-pound weight loss over three months in that study, which tested the drug in 97 patients on olanzapine or clozapine with prediabetes and a mean BMI of 34 kg/m². By comparison, metformin brought about a seven-pound weight loss in studies of a similar duration. Like metformin, liraglutide led to improvements in metabolic variables: glucose tolerance, blood pressure, and LDLs (Larsen JR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74(7):719–728).

The high cost of the GLP-1 agonists has slowed their adoption in psychiatry, but a generic liraglutide is slated for release in 2024. Both drugs are delivered by subcutaneous injection, although their half-lives lend an advantage to the weekly semaglutide over the daily liraglutide. The sole head-to-head comparison of these two also favors semaglutide, which brought about a 16% vs 6.4% reduction in body weight in a 68-week randomized controlled trial of 338 obese patients without diabetes (sponsored by semaglutide’s manufacturer) (Rubino DM et al, JAMA 2022;327(2):138–150).

The most common side effects with GLP-1 agonists are nausea, diarrhea, and constipation. The medications slow gastric emptying, and the FDA recently placed a warning on semaglutide for intestinal blockage (ileus). Common warnings across the -glutides are thyroid cancer, acute kidney injury, gallbladder disease, and pancreatitis.

Metformin and GLP-1 agonists can be safely combined with Lybalvi, but the two antidiabetic medications (metformin and GLP-1 agonists) bring an additive risk of hypoglycemia if used together.

CARLAT VERDICT

Metformin and the -glutides have broader benefits than the FDA-approved Lybalvi. Start metformin early for prevention of weight gain. For patients whose BMI rises above 30 kg/m² (or 27 kg/m² with medical complications), the GLP-1 agonists are FDA approved and appropriate to use with antipsychotics.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)