Culturally Competent Assessment

Dakota Carter, MD, EdD. Medical Director and Chair of Psychiatry, Eisenhower Behavioral Health, Eisenhower Health, Rancho Mirage, CA.

Dakota Carter, MD, EdD. Medical Director and Chair of Psychiatry, Eisenhower Behavioral Health, Eisenhower Health, Rancho Mirage, CA.

Dr. Carter has no financial relationships with companies related to this material.

CCPR: How do you define cultural psychiatry?

Dr. Carter: Cultural psychiatry involves focusing on the individual, their family, and their community, with the aim of creating a comfortable environment to gather as much information as possible, enabling more effective care within their cultural context.

CCPR: Can you give an example of a patient with whom you utilized this approach?

Dr. Carter: I saw a first-generation American transitional-age youth from a Korean background. She had depressive symptoms that had progressed into psychosis. Her parents did not speak English. We talked about her goals as a first-generation American and her family’s expectations. She was an art student, but her parents expected her to study sciences and math. The family had been taking her for Eastern medicine treatments over the course of two to three years. She became psychotic about a year before I saw her. Her family cared for her at home until she became violent and ran into traffic. They sought Western care only once she was incredibly ill.

CCPR: When families have avoided Western treatment, how do you ask about symptoms in a respectful manner?

Dr. Carter: Never blame them (“Why didn’t the family seek help?”). Even if we don’t express blame directly, it can come across in our tone. Be curious: “Help me understand your concerns.” For this patient, we learned that her grandmother in Korea had depression with psychosis that was managed in a similar way. Her family was terrified that something spiritual was happening. They were convinced that they had done something wrong to make it happen.

CCPR: Was this all culturally consistent?

Dr. Carter: Yes. It is important to understand cultural concepts of human behavior. Spirits inhabiting a person due to the actions of family members is part of Korean culture (www.tinyurl.com/3kz5wnkd). Once we accepted this, we had conversations with the family about stigma and shame. She was a gifted student, which can bring honor to the family, but they didn’t want the stigma of her mental illness. We talked about honor, disrespect, and the fear of how she would be perceived.

CCPR: How did you assess her symptoms?

Dr. Carter: We took time with the family to explain what a depressive syndrome looks like and asked what symptoms they had seen in her and in their family. I worked with an interpreter to understand the family dynamic and get a family history. A layperson from any culture might not talk about these issues, and some cultures tend to talk about them even less than others. If we diagnose “major depressive disorder, recurrent, severe with psychotic symptoms,” how do we explain this diagnosis to families with no knowledge of mental health care? Try to understand their experience and what led to the family decisions, then connect the symptoms with your diagnosis. Introduce the concept of psychosis, including signs and symptoms: “We think that some people have these experiences due to a neuropsychiatric condition that can be treated.”

CCPR: What is your general approach to assessing patients in families from different cultures?

Dr. Carter: Talk about the patient and discuss context. What is the family’s experience with mental health? Has that been positive or negative? What is their language around mental health? How is mental health discussed? Learn about their environment. Some cultures delay care. Do they fear the health care system? Think about how their individual differences developed in the context of their family and community. Did they have family or educational supports? How much have socioeconomics or intersectionality played a part? You cannot understand by checking boxes for a particular “XYZ” diversity. You need to understand the whole individualized contextual picture.

CCPR: Do you vary your approach when working with different cultural or ethnic groups?

Dr. Carter: I have a general approach with every patient and family, starting with empathy and kindness. Avoid assumptions. It’s easy to see someone’s name or background and assume their ethnicity or experience. Stay humble in each interaction. We’re all capable of implicit bias or expectations based on our own experiences: “This is my understanding of your culture. How much of this is relevant to you?” Be ready to learn—a patient might respond “Nope, you are totally wrong on that” or “Some of that is relevant to my life, but this is how it doesn’t fit in.” Cultural psychiatry is about being willing to learn from your patients.

CCPR: What other questions do you ask?

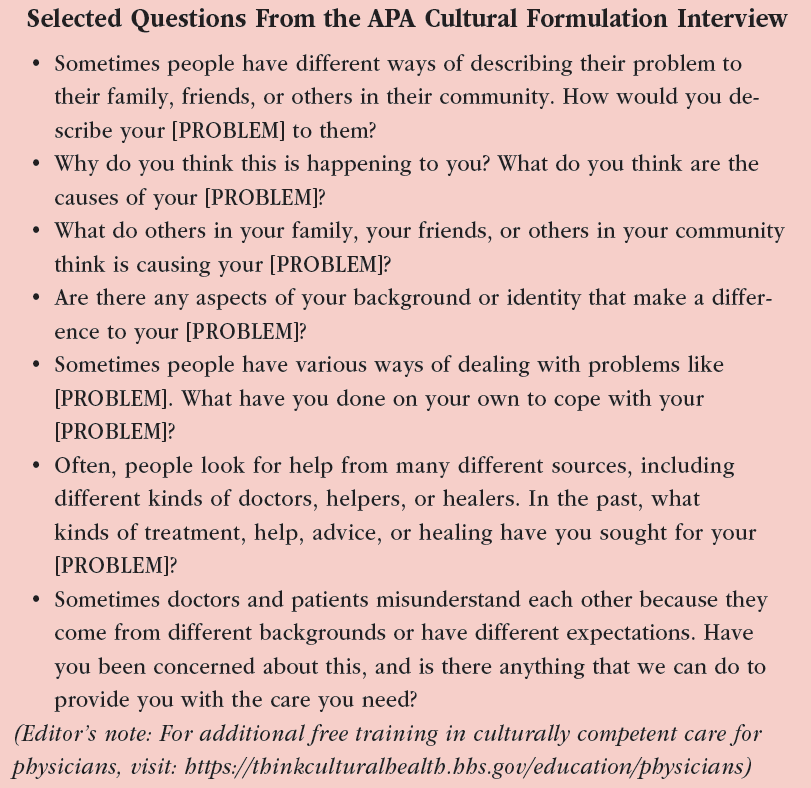

Dr. Carter: I use questions like the ones found in the American Psychiatric Association Cultural Formulation Interview: “Sometimes people have different ways of describing their problem to their family, friends, or others in their community. How would you describe your [PROBLEM] to them?” And: “Why do you think this is happening to you? What do you think are the causes of your [PROBLEM]?”

CCPR: Any other suggestions for how to approach the interview?

Dr. Carter: Look at the impact of symptoms on the patient and the family in their cultural context, including family history, treatment barriers, and use of non-Western interventions (www.tinyurl.com/4fmw55kn). We published a book in 2021 that included chapters on various ethnicities, religions, sexualities, and genders (Parekh R et al, eds. Cultural Psychiatry With Children, Adolescents and Families. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC; 2021). In the book, we talk about refugees and folks who are adopted. We have a conversation about rural versus urban youth. And we talk about intersectionality. Start by looking at the nuances of the population. Every chapter refers to the Cultural Formulation Interview, talking about such things as social networks and psychosocial stressors. (Editor’s note: For more specific examples of culturally competent interview questions, see “Selected Questions From the APA Cultural Formulation Interview” box.)

CCPR: Do you use common assessment scales such as the Childhood Depression Inventory or the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale?

Dr. Carter: That depends on an individual’s understanding of the material. If you’re doing the Columbia scale and the patient looks confused, that could mean a lot of things. When I was a resident, I used an interpreter to administer a Montreal Cognitive Assessment to an Urdu-speaking woman of Arab descent. She had never seen a rhinoceros, and there’s no word for velvet in Urdu, so the test was meaningless for her. You can’t translate a scale and assume that it will accurately assess the patient. It’s better to have a conversation that covers the concerns. Many patients are illiterate. One circled all 3s on a GAD-7, thinking that 3 meant good. We’ve sent out Vanderbilt scales for ADHD where parents did not read in English and had the patient’s oldest sibling fill in questions about discipline, behavior, inattention, and hyperactivity.

CCPR: How do you address language barriers?

Dr. Carter: You need qualified interpreters. Your state medical board or clinic manager should have referral resources for good interpreters. I had a person translating from English into Spanish, and I could tell they were not asking what I had asked. Patients and families are usually more comfortable with their primary language; however, it is difficult to find clinicians who are fluent even in Spanish. (Editor’s note: See CCPR July/August/September 2020 on using interpreters in psychiatric practice.)

CCPR: What other barriers do you encounter in cross-cultural psychiatry?

Dr. Carter: Two other barriers are follow-up and education. Families may assume that you take a pill or talk to a therapist once and it’s fixed. In many cultures, care is guided by parents who may be reluctant to share history or participate in family therapy.

CCPR: Do you enlist members of the person’s cultural community to help?

Dr. Carter: Yes, it can be very helpful. Native populations often distrust health care systems, and liaisons from community organizations such as tribal councils can bring you into conversations with families and patients. There is also a big role for religious and spiritual liaisons in these conversations. This can help in broader community contexts too. During my residency, I had friends who started a radio show for the local Vietnamese population, providing education on depression and anxiety. Many folks came to the clinic referencing that radio show. In clinical practice, cultural psychiatry is a team-based approach, and so you’re utilizing the folks that are surrounding the patient, making sure that everybody’s on the same page and that everybody is working together. There are lots of interdisciplinary meetings and lots of conversations around how to help kids.

CCPR: How can a busy clinician stay connected with all those people?

Dr. Carter: Work with your team of social workers, case managers, and psychiatric nurses to have those conversations. Work with the family and respect their time too. Don’t be afraid to delegate using a team-based approach to target some of these issues. We look for staff who might have a familiar connection that the patient and family can relate to for case management. Many organizations have an identified “liaison” for a specific community, eg, Native American, LGBTQIA+, etc. This can also include native speakers/interpretation services. You can also ask families if they have anyone in their community whom they would like included in collaboration around culture and health issues.

CCPR: How did you talk to your depressed, psychotic patient and her family?

Dr. Carter: For this patient and family, we explained mental health in Western medicine, including separation from family during inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. This was very concerning to the family. They were also concerned about what medications would do to the patient’s personality and how they would affect her over the long term. It was an interesting dynamic. I tried to incorporate everyone’s goals and perspectives. We cannot create a perfect treatment plan for everybody, but we can look for something that makes the particular patient and family feel at home, more engaged, more able to decide about whether to use medication. There’s no “one size fits all” approach, so in each situation, try to understand the nuances. Remain humble, ask the questions, be there for support. And take the punches, too. There will be miscommunications and there will be times when things aren’t going well, but you need to come back and address everyone’s intersectional needs.

CCPR: Is there research on treatment efficacy and outcomes with culturally informed assessment?

Dr. Carter: These principles apply to all patient care, but they are hard to study because of the individual nuances of nature versus nurture in the context of culture. Some studies demonstrate the impact of cultural humility on outcomes. These studies underscore the impact on treatment engagement and adherence to treatment plans. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry has a practice parameter on incorporating cultural competency into psychiatric practice that notes the positive impact doing so can have on outcomes. You can be a great cultural psychiatrist if you remember kindness, empathy, and humanity and stay ready to learn and engage. You can learn from your patients, incorporate appropriate cultural ideas, and improve mental health.

CCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Carter.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)