A Therapeutic Approach to Schizophrenia

Mark L. Ruffalo, MSW, DPsa

Mark L. Ruffalo, MSW, DPsa

Editor-in-Chief, The Carlat Psychotherapy Report. Psychotherapist in private practice in Tampa, Florida. Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Central Florida College of Medicine and Adjunct Instructor of Psychiatry at Tufts University School of Medicine.

Dr. Ruffalo has no financial relationships with companies related to this material.

TCPR: How do you establish trust with patients who have psychosis?

Dr. Ruffalo: Shorter sessions are more appropriate for psychotherapy with schizophrenia, like 30 minutes instead of the usual 45–50 minutes. Longer sessions tend to increase the patient’s interpersonal anxiety. Another tip is to allow the patient an adequate degree of freedom in the therapy space. For instance, if the patient wants to get up off the couch and walk around the room, I let them do that. If the patient wants to talk about something that doesn’t, on the surface, seem all that important, I let them do that (Ruffalo ML, Psychiat Clin Psychopharmacol 2023;33:222–228).

TCPR: How long does it take to establish trust?

Dr. Ruffalo: It may take many weeks or months for them to feel comfortable in session, but once they are, they begin to open up about their inner world. They may tell us things they have not revealed to any other person on earth. As psychoanalyst Silvano Arieti said, “Sooner or later, the patient gives us the gift of trust.” And a gift it is, indeed.

TCPR: What else improves the alliance?

Dr. Ruffalo: I look for what they are interested in. It helps to relate on a shared topic, like sports or movies. If the patient mentions a streaming show, I may not watch it, but I will at least read about it. That helps them feel that they are understood, that I care about them and am interested in the way they see things. To paraphrase Harry Stack Sullivan, the patient must feel that he is no longer alone in the world in his relations with the therapist. This also goes better in person, rather than through telehealth (Krupnik V, Contemp Psychother 2023;53:207–215).

TCPR: How do you handle personal questions that patients ask?

Dr. Ruffalo: I tend to be a bit more liberal in my use of self-disclosure with schizophrenia patients. I may talk about day-to-day life, my own interests and hobbies, etc. I believe in boundaries and the therapeutic frame, but sometimes declining to answer questions can backfire because it gives the sense that you are closed off or not real. This is especially important in the early stages of treatment, where the patient needs to have that sense that you’re a real person who shares in their experience of the world.

TCPR: What goals do people with schizophrenia bring to therapy?

Dr. Ruffalo: A common one is to rejoin the social fabric of life, to regain some ability to develop and maintain relationships.

TCPR: How do you help someone with minimal social skills build a social world?

Dr. Ruffalo: It takes time, but there is usually some improvement within a year. You start with more reachable goals. For instance, you might propose “Why don’t you text an old friend this week? Why don’t you reach out to someone on Facebook whom you’d like to talk to but haven’t spoken with in a long time, perhaps since before you fell ill?” Gradually they get more comfortable in social settings, and as their relational life improves, their symptoms decrease.

TCPR: How does this lead to symptomatic improvement?

Dr. Ruffalo: Take a patient who hears critical voices telling him that he’s no good, that he doesn’t deserve to live, that he should kill himself. As he builds a better life, his self-esteem will improve. He might tell you “Well, you know, I was able to do voc rehab, and that helped me get a job, and now I’m meeting some people there who want to hang out outside of work.” Through this, we work on his perspective of himself and gain some distance from the negative voices. If he can understand that the voices are not real but representations of his own views about himself, they become less threatening. A patient at a later stage of treatment might be able to tell you that they transform their feelings about themselves into concrete delusions and hallucinations.

TCPR: How do you build the motivation to change?

Dr. Ruffalo: I’ll ask them to imagine what it would feel like if they made those changes. “How would you feel different about yourself if you got this job?” or “What would it mean to you if that person you’d like to get to know agreed to meet you for breakfast?”

TCPR: What problems do patients with schizophrenia encounter as they take on the challenges of jobs and new relationships?

Dr. Ruffalo: A common problem is that other people interpret their flat affect and other negative symptoms as disinterest, like “He doesn’t smile at me. He’s not laughing at my jokes, so he must not like me.” Patients are often quite attuned to this problem, to the way that other people see them as different or odd. This has to be handled very delicately in psychotherapy. If we can teach and role-play some skills, if we can model for the patient some social interaction in the session, then slowly over time the patient may begin to feel a bit more comfortable in these settings and approach a more normal interaction.

TCPR: Do you role-play conversation skills, like asking them to tell you about a movie they saw?

Dr. Ruffalo: Yes. In my experience the practice they need often has to do with relationships, with asking someone out, with approaching someone they are interested in. They might ask “What should I say? I’d really like to ask her out.” Role-playing is also helpful for job interviews and interactions with family. You can also teach social skills, basic things like eye contact—not too much, not too little; respecting personal space; smiling; give-and-take in conversation; starting and ending conversation (Turner DT et al, Schizophr Bull 2018;44(3):475–491). But I wouldn’t jump into these skills too soon.

TCPR: What is the risk of attempting to tackle these skills too soon?

Dr. Ruffalo: Sometimes the lack of eye contact and social reciprocity makes the therapist uncomfortable, and if the therapist is unaware of their own countertransference, they might jump into social skills too soon, which can backfire. Therapists get into trouble when they go into “problem-solving” mode before there is sufficient trust in the treatment relationship. The patient has to be comfortable in the therapy room first.

TCPR: What do you tell patients about their diagnosis?

Dr. Ruffalo: When it comes to naming the disorder, actually calling it what it is, I think this is something that we ought to think about on a case-by-case basis. I think some people are very quick not just to apply a diagnosis, but to inform the patient of the diagnosis. And while in many cases this can be helpful, I think in some cases it can be detrimental and harmful, especially early on in the treatment. Now with that being said, I certainly believe in psychiatric diagnosis and I certainly believe in the concept of schizophrenia. But whether or not we should introduce that to the patient is a more delicate clinical question, and I think it warrants a little bit of care.

TCPR: Some patients get demoralized about the diagnosis. How do you work with that?

Dr. Ruffalo: When it comes to prognosis, I follow the patient’s lead. Some come right out and ask “Am I going to get better?” It’s important to deal with this very carefully and not overpromise things, while also not underpromising or relaying a grim outlook. Even if the prognosis is poor, we need to be supportive, to help with day-to-day problems that occur in life. Often there is some connection that can be made with the therapist, and that alone may ward off potential suicide. It is early in the course of the illness that the risk of suicide is highest.

TCPR: How do you help people with schizophrenia manage their psychotic symptoms?

Dr. Ruffalo: One way is to teach them to adopt a “listening attitude.” Just before a hallucination, patients often have a brief moment of heightened sensation where they expect the hallucination is coming on. If they can catch themselves in this momentary state, the frequency and intensity of the hallucinations will decrease (Ruffalo ML, Psychoanal Soc Work 2019;26:2;185–200).

TCPR: Where does that idea come from?

Dr. Ruffalo: It was developed by Silvano Arieti, a psychoanalyst who tried to bring together psychological and biological theories of schizophrenia in the 1960s and 1970s. More recently his theory was validated by Ralph Hoffman’s group at Yale. Using fMRI, they found activation in the left insula just before a hallucination. This is the same part of the brain that gets activated when people—all people—hear ambiguous sounds and try to make sense of them. Those pathways seem to go awry in schizophrenia. Hoffman calls it a “prehallucination auditory expectancy” (Hoffman RE, Schizophr Bull 2010;36(3):440–442).

TCPR: Are you helping patients gain awareness of that moment, before it goes awry?

Dr. Ruffalo: Yes. It gives them some ability to control when and how they experience a hallucination. Of course, this doesn’t hold true for every patient. For some patients this technique falls flat and doesn’t work. But for others it is quite helpful.

TCPR: How do you help them gain that awareness?

Dr. Ruffalo: I ask “What is it that you felt right before you heard that voice?” They may say “There was just something that changed. I just came to expect something to happen there.” Often it’s a feeling of fear, of foreboding, which may be related to their paranoia.

TCPR: Once they recognize the space, what do they do?

Dr. Ruffalo: Just the act of recognizing it is enough to give them more control over the symptom and reduce the frequency of the hallucinatory experience. They gain control over what they pay attention to. Let me add caution. I’m not saying that patients are responsible for their symptoms. But there is a common theme in psychotherapy of helping patients take on a more active role in reducing those symptoms.

TCPR: Can you give an example?

Dr. Ruffalo: Here is something a patient shared about their growth (they gave permission to publish):

“The work didn’t click for me until years in. Every psychotic experience was always preceded by a split-second shift in my emotional state. Over time, I was able to feel this window open up, and my experiences slowly dissipated. I still experience psychotic symptoms but at a much less frequent rate. Every session, a new layer of what has happened to me has unraveled through therapy. Almost every time a link has been discovered, I subsequently experience fewer symptoms.”

TCPR: Any tips on working with patients’ families?

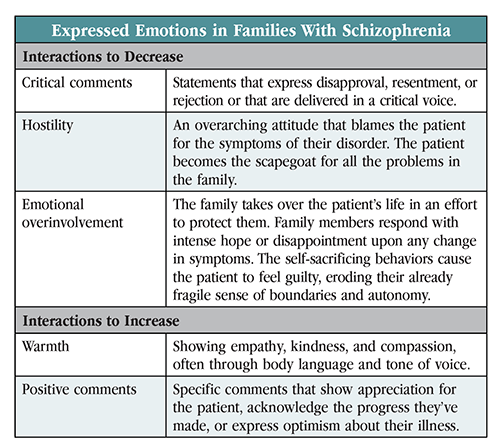

Dr. Ruffalo: One thing I emphasize for families is to do whatever they can to minimize the degree of anxiety in the household. This relates to research going back to the 1960s where they found that higher levels of expressed emotion in the home increase the risk of relapse in schizophrenia. (Editor’s note: The three types of expressed emotion are described in the table “Expressed Emotions in Families With Schizophrenia”: critical comments, hostility, and emotional overinvolvement, along with two that reduce relapse rates: warmth and positive comments.) Families with high levels of expressed emotion are two to four times more likely to experience relapse, and in controlled trials those relapse rates go down when we help families reduce those heated interactions (Ma CF et al, Psychol Med 2021;51(3):365–375).

TCPR: So the idea is to help families recognize and reduce those types of emotional expression?

Dr. Ruffalo: Yes. Families need to lower their demands, reduce conflict, avoid sensory overstimulation, and allow the patient to have their own space and to operate with reasonable freedom in their day-to-day life. By “reasonable” I mean with some constraints to avoid serious harm (Kavanagh DJ, Br J Psychiatry 1992;160:601–620).

TCPR: What books do you recommend for families?

Dr. Ruffalo: Surviving Schizophrenia by E. Fuller Torrey is a good one (Harper; 2019). It offers strategies for day-to-day affairs when a family member has active psychosis. Silvano Arieti also wrote a family guide titled Understanding and Helping the Schizophrenic: A Guide for Families that takes a more psychological approach. The National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) also offers courses for families in many communities.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Ruffalo.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)