Lecanemab Breaks Thin Ground in Dementia

On July 5, 2023, the FDA approved lecanemab (Leqembi) in Alzheimer’s dementia. The drug has been called “groundbreaking,” but the ground it stands on is not very firm, with questionable efficacy, a $26,500 annual cost, and a 12.6% risk of cerebral edema.

Lecanemab vs aducanumab

In one sense, lecanemab does break new ground. It is the first amyloid-reducing medication to demonstrate clinical efficacy in dementia, something that cannot be said for aducanumab (Aduhelm), the other antiamyloid medication. While lecanemab has full FDA approval, aducanumab earned only provisional approval in 2021 under an “accelerated” pathway that allows investigational drugs to enter the market before they are fully investigated (van Dyck CH et al, N Engl J Med 2023;388(1):9–21). Accelerated approval is the result of a long struggle between the FDA and the public that began in 1988 when AIDS activists occupied the FDA headquarters demanding faster access to investigational therapies. The accelerated pathway speeds access to promising but unproven drugs, with the expectation that the bulk of the safety and efficacy data will be gathered after the launch.

Aducanumab failed in its clinical trials, but was approved because it reduced a biomarker for Alzheimer’s: amyloid plaques. Medicare has refused to cover this drug, which is slotted to come off the market in 2024 due to low sales. Meanwhile, lecanemab has earned full FDA approval and comprehensive Medicare coverage.

Meaningful efficacy?

Lecanemab also reduces amyloid plaques, and like its predecessor it began with disappointing clinical results. It failed to make a difference in its first randomized trial of 856 patients (Swanson CJ et al, Alzheimers Res Ther 2021;13(1):80). That was followed in early 2023 by the larger Clarity trial, which is the first and only trial to show a statistically significant difference in clinical outcomes with antiamyloid therapy. In Clarity, lecanemab did not improve cognition, but it slowed the decline by 27% compared to placebo after 18 months in 1,795 patients ages 50–90 (average 71) in the early phase of Alzheimer’s disease (van Dyck et al, 2023).

There are several reasons to be skeptical of these results. First, they arrived on the heels of 14 negative trials of antiamyloid drugs (Ackley SF et al, BMJ 2021;372:n156). Most of these were undertaken in patients who were in the early phase of Alzheimer’s or had mild cognitive impairment. Second, lecanemab’s positive study enrolled a highly selective population. Only 30% of those screened met the inclusion criteria, which limited the population to those with active amyloid plaques, no more than mild cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Exam score ≥22), no ischemic brain disease, and no active medical or psychiatric illness (Walsh S et al, BMJ 2022;379:o3010).

Finally, although slowing the decline by 27% sounds impressive, many believe the difference is so small that it won’t be appreciated by patients or their caregivers. Researchers estimate that a 0.98–1.63 point reduction in the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) is needed to make a meaningful difference, but lecanemab only reduced the CDR by 0.35–0.62 relative to placebo. By comparison, donepezil (Aricept) reduced the CDR by 0.69 in Alzheimer’s and is estimated to slow the rate of decline by 25%–50% per year (Rogers SL, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1998;9 (Suppl 3):29–42).

The risk: amyloid-related imaging abnormalities

Lecanemab’s ability to remove amyloid plaques is its main selling point, but this is also responsible for its main risk: cerebral edema, officially known as amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIAs). These occurred in 12.6% of treated patients. Most ARIAs are asymptomatic, although intracerebral hemorrhage and death can occur. ARIAs are detectable on an MRI, which is required at baseline and approximately every three months during treatment. ARIAs are more common in carriers of the apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 (APOE-ε4) gene, and testing for this gene is required before starting lecanemab. APOE-ε4 is also a risk factor for Alzheimer’s dementia.

Lecanemab’s other burdens are tolerability and price. The IV infusions, which last an hour and are delivered every two weeks, can cause nausea and flu-like symptoms. Most Medicare plans will pay 80% of the $26,500 annual cost of the drug, and the out-of-pocket costs for the required scans are unclear (on average, the full price is $6,000 for the initial PET scan and $4,000–$6,000 annually for the MRIs).

Other options

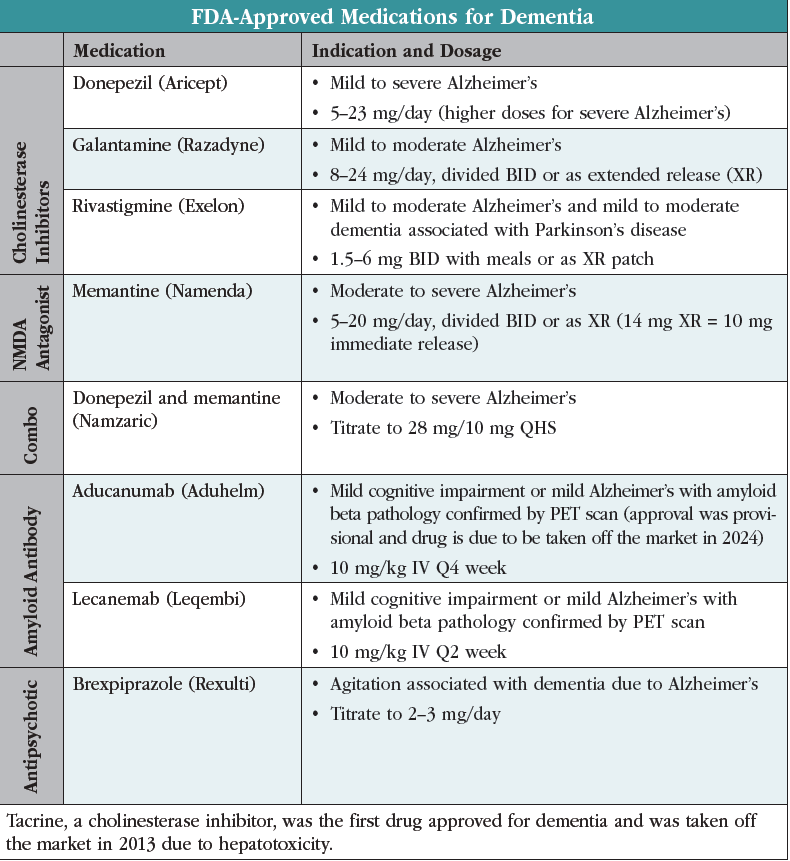

Central to lecanemab’s approval is the idea that it changes the course of the disease by removing amyloid plaques. However, amyloid is just one of many potential causes of Alzheimer’s. Other FDA-approved options address potential mechanisms as well, like elevations of glutamate (memantine) and acetylcholine (cholinesterase inhibitors), and some even lower amyloid plaques, although to a lesser degree than lecanemab (Saeedi M and Mehranfar F, Recent Pat Biotechnol 2022;16(2):102–121). Tau proteins are another mechanism under investigation. Like lecanemab, none of these approved medications improve cognition. All of them slow the progression of the disease, and there is no evidence that lecanemab brings superior safety or efficacy to the table.

Current guidelines recommend starting with a cholinesterase inhibitor in Alzheimer’s dementia. All have comparable efficacy, and donepezil—which has approval in all levels of severity—is a reasonable first choice (Grossberg GT et al, J Alzheimers Dis 2019;67(4):1157–1171). If needed, donepezil can be augmented with memantine. The combination has FDA approval as Namzaric (generic substitution of the separate medications is acceptable, but keep in mind that Namzaric contains extended-release [XR] memantine, and 14 mg of XR memantine = 10 mg of immediate-release memantine). Compared to donepezil alone, the combination reduces cognitive decline (small effect size), improves functioning (medium effect size), and reduces psychiatric and behavioral symptoms (large effect size) (Chen R et al, PLoS One 2017;12(8):e0183586).

Current guidelines recommend starting with a cholinesterase inhibitor in Alzheimer’s dementia. All have comparable efficacy, and donepezil—which has approval in all levels of severity—is a reasonable first choice (Grossberg GT et al, J Alzheimers Dis 2019;67(4):1157–1171). If needed, donepezil can be augmented with memantine. The combination has FDA approval as Namzaric (generic substitution of the separate medications is acceptable, but keep in mind that Namzaric contains extended-release [XR] memantine, and 14 mg of XR memantine = 10 mg of immediate-release memantine). Compared to donepezil alone, the combination reduces cognitive decline (small effect size), improves functioning (medium effect size), and reduces psychiatric and behavioral symptoms (large effect size) (Chen R et al, PLoS One 2017;12(8):e0183586).

These first-line therapies are safer than lecanemab. Their main risk is tolerability. For cholinesterase inhibitors, that means dizziness, nausea, low appetite, and diarrhea. For memantine, headache, confusion, and somnolence are common.

Antipsychotics are best avoided in dementia as they raise mortality risks and interfere with the benefits of cholinesterase inhibitors. Most bring little benefit for agitation, with the exception of brexpiprazole (Rexulti), which was FDA approved for this use in 2023. The approval was based on two three-month randomized controlled trials involving 703 patients, which found efficacy at 2 mg/day but not at lower doses (Grossberg GT et al, Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2020;28(4):383–400). For a quick visual, see the table “FDA-Approved Medications for Dementia.”

None of these treatments have problematic interactions with lecanemab, but it is not yet clear where the IV infusion fits in the algorithm for Alzheimer’s dementia.

CARLAT VERDICT

Lecanemab’s ability to reduce amyloid plaques raises hopes that it will alter the course of Alzheimer’s disease, but so far, those hopes are unproven. Instead, amyloid reduction causes cerbral swelling for one in eight patients.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)