Listen to Your Levels: Effective and Safe Prescribing of Lithium

Though it has long been an indispensable treatment incorporated into multiple treatment guidelines, lithium’s use has been in decline. The underutilization of this essential medicine stems, in part, from bothersome side effects, interactions with many drugs, and a narrow therapeutic window beyond which it can reach toxic levels. Here’s a rundown on how to use lithium safely and effectively, including in special populations.

Why we use lithium

Lithium is a first-line medication for the treatment of acute bipolar mania and maintenance management of bipolar I disorder. While it has been used to manage acute bipolar depression in both bipolar I and II disorders, I remain unconvinced about its effectiveness for these conditions, and a recent meta-analysis found no significant benefit of lithium versus placebo or antidepressants (Rakofsky JJ et al, J Affect Disorders 2022;308:268–280). Lithium works well for treating postpartum psychosis, augmenting antidepressant therapy for unipolar depression, alleviating mood symptoms in primary psychotic disorders, and curtailing impulsivity and aggression in conditions ranging from neurodevelopmental disorders to personality disorders. The therapeutic range for lithium is generally 0.6–0.9 mEq/L, as this range provides the best balance of effectiveness and safety (Geddes JR et al, Lancet 2013;381(9878):1672–1682). Despite multiple studies indicating an inherent antisuicide effect of lithium, a recent study found no decrease in suicide-related events when lithium was incorporated into treatments for major depression or bipolar disorders among veterans (Del Matto L et al, Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2020;116:142–153; Katz IR et al, JAMA Psychiatry 2022;79(1):24–32).

Watch out for kidney problems

Lithium causes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, so patients will probably find they urinate more frequently. Long-term use of lithium can lead to chronic kidney disease, especially in older patients and patients who have had elevated lithium blood levels. If you’re prescribing lithium, keep an eye on your patients’ kidney health. It’s essential to perform regular checks of patients’ estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)—a measure of kidney function. An eGFR of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is considered abnormal, though eGFR declines with normal aging and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2 may be a more appropriate cutoff value for patients 65 years and older. Reduce the dose or discontinue lithium altogether in patients with an eGFR of 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2.

I recommend obtaining an eGFR at the start of treatment, once the patient’s lithium level is therapeutic, and every six months to one year afterward. You can reduce the risk of nephrotoxicity from lithium by utilizing the immediate-release formulation dosed all at night and maintaining levels between 0.6 and 0.8 mEq/L.

Dehydration or sudden changes in diet—especially shifts in sodium consumption—can directly impact lithium levels in the body. Certain nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), like ibuprofen and naproxen, can also raise lithium levels. Advise your patients to steer clear of these drugs, or at least to let you know if they are planning to take an NSAID, and opt for alternatives like aspirin or acetaminophen instead.

Diuretics and other antihypertensive drugs affect lithium’s excretion in different ways depending on their action in the renal tubule. Thiazides, such as hydrochlorothiazide, elevate lithium levels by 25%–30%. In contrast, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors like enalapril, angiotensin-II receptor blockers like losartan, loop diuretics like furosemide, and potassium-sparing diuretics like amiloride or spironolactone influence lithium levels in a less predictable manner. Mannitol, theophylline, and acetazolamide, on the other hand, reduce lithium levels (see “Factors That Can Affect Lithium Levels” table for more).

Review your patient’s medication list, especially if they’re on medications for hypertension or pain, and monitor for new medications that could affect lithium levels. If a patient must take an NSAID or diuretic for whatever reason, you can still prescribe lithium as long as you obtain regular lithium levels and modify dosing as needed.

Take lithium toxicity seriously

Overdose on lithium is a medical emergency. Fewer than 1% of patients with toxic exposure to lithium die, but they may experience long-term central nervous system (CNS) effects that can reduce their quality of life. Symptoms range from weakness, nausea, diarrhea, impaired concentration, and mild ataxia at mild toxicity (1.5–2.0 mEq/L) to confusion, seizures, cardiovascular collapse, and even death at severe toxicity (>4 mEq/L).

If a patient shows signs of lithium toxicity, stop the medication immediately. Mild cases will resolve on their own, but moderate toxicity often requires fluid infusion, gastric lavage, and bowel irrigation, while severe lithium toxicity typically requires hemodialysis. Chronic poisoning resulting from exposure to high lithium levels over several weeks poses the greatest risk for both severe toxicity and long-term CNS sequelae (Baird-Gunning J et al, J Intensive Care Med 2017;32(4):249–263).

Managing other side effects

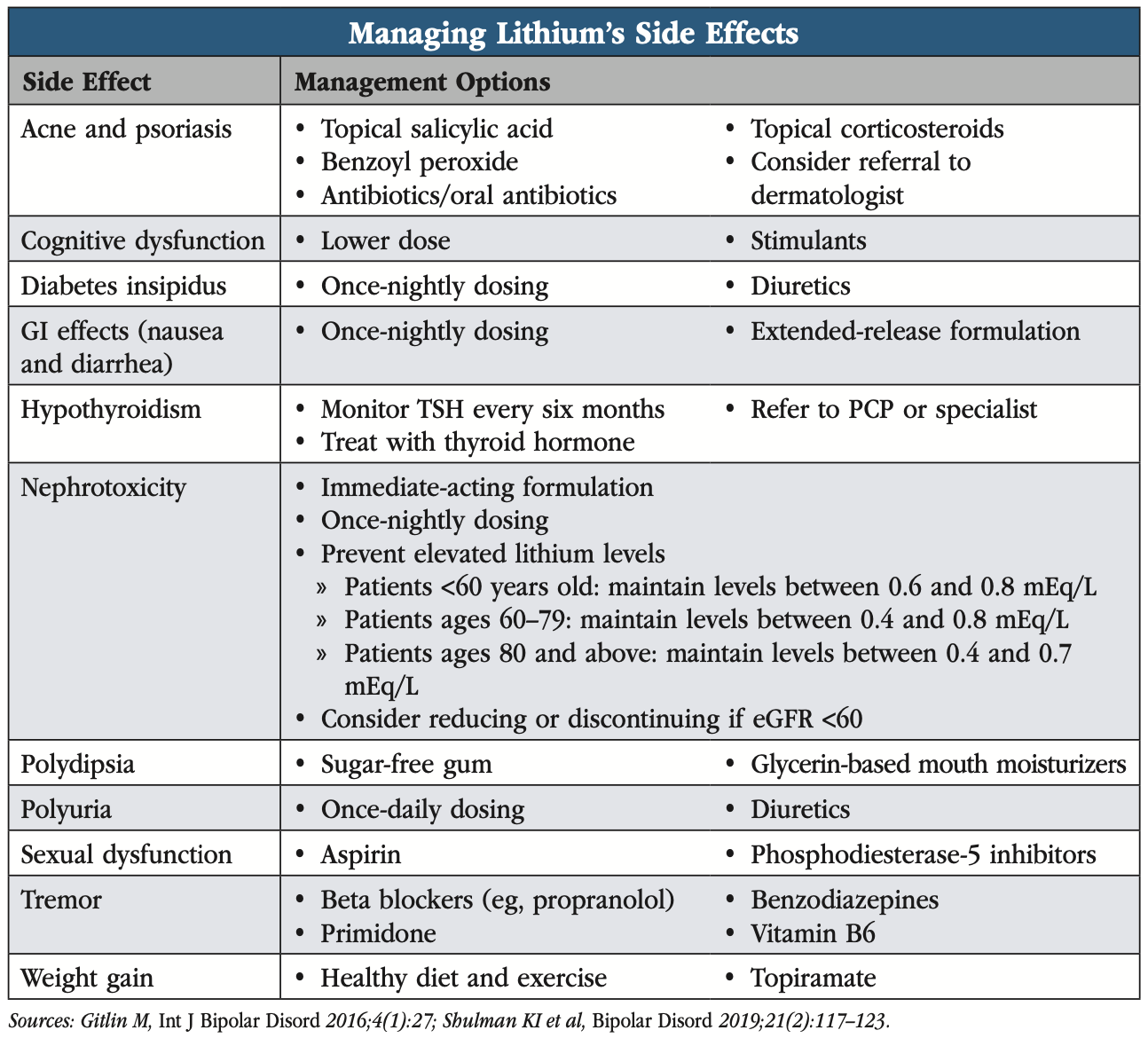

Common side effects of lithium include tremor, weight gain, and thyroid problems (see “Managing Lithium’s Side Effects” table). Lithium-induced thyroid dysfunction, occurring in over 25% of patients, ranges from subclinical hypothyroidism to goiter. Risk factors include the presence of antithyroid antibodies, female sex, older age, and a family history of hypothyroidism. Don’t be too quick to stop lithium if this side effect arises. The patient can continue taking lithium while also getting thyroid hormone supplementation.

Other common side effects include polyuria (excessive urination), polydipsia (excessive thirst), dry mouth, and cognitive dulling. Less frequently reported are sexual dysfunction, acne, psoriasis, and hyperparathyroidism leading to increased serum calcium. Many of these problems can be managed with nonpharmacologic measures or medications (see table for management options). Despite reports of cognitive dulling on lithium, several studies have reported lithium may be a neuroprotective agent against neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease (Forlenza OV et al, ACS Chem Neurosci 2014;5(6):443–450). Regardless, discuss side effects with your patients to assess whether the benefits of lithium treatment are worth the risks. You may want to consider an alternative agent in patients with baseline renal impairment, cardiac conduction disorders, or cardiovascular disease.

Lithium in special populations

Lithium in special populations

For patients considering pregnancy, discuss lithium’s potential risks to the fetus. Prenatal lithium exposure increases the risk of fetal cardiovascular anomalies in a dose-related manner. If maternal lithium levels are kept under 0.64 mEq/L, on doses of 600 mg per day or less, there appears to be no increased risk of fetal cardiac malformations (Fornaro M et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(1):76–92).

If you and your patient agree to treat with lithium during pregnancy, check lithium levels closely as levels tend to decline due to an increased volume of distribution and greater renal clearance. Monitor lithium levels monthly during pregnancy and again immediately after delivery, changing dosing as needed (see CHPR Oct/Nov/Dec 2023 for more on lithium and pregnancy).

Lithium remains a first-line treatment for mania in the elderly. Renal function declines in elderly patients, and they are more likely than younger patients to be taking additional medications that may affect lithium’s renal excretion. These factors place them at increased risk of lithium side effects, so aim for lower lithium levels in elderly patients (see “Managing Lithium’s Side Effects” table). Elderly patients typically respond to lower serum concentrations and can develop signs of lithium toxicity at much lower levels than younger patients. Start with a low dose and increase slowly, checking lithium levels after each dose increase.

CARLAT VERDICT

Lithium remains the gold standard for managing bipolar disorder, with notable efficacy in treating mania and providing maintenance therapy for bipolar I disorder. Though it may affect renal and thyroid function, these side effects can be managed with a few simple steps. Lithium has a narrow therapeutic window, so be vigilant for signs of lithium toxicity. With the right precautions, lithium provides a safe and effective treatment for many patients.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)