Wisdom in Psychiatry

TCPR: How did you become interested in wisdom?

Dr. Jeste: In the 1990s I was researching schizophrenia and aging at UC San Diego, and I noticed something that did not make sense. As people with schizophrenia got older, their symptoms started getting better (Jeste DV et al, Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003;107(5):336–343). How could we explain that? Their physical health declined faster than the general population, but their mental health improved. I thought “Maybe the notions we have about aging are wrong.”

TCPR: What did you learn from there?

Dr. Jeste: I went on to direct an institute for research on aging at UC San Diego. We started a study of 1,500 randomly selected San Diegans from age 20 to 100. We looked at their physical health and mental health and we saw the same thing as we did with schizophrenia. Physical health declined with age, but mental well-being actually improved. People who were wheelchair-bound in their 80s were happier than healthy people in their 20s (Thomas ML et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2016;77(8):e1019–e1025).

TCPR: What were your thoughts on that?

Dr. Jeste: At that point I recalled something I had learned growing up in India. There, we are taught that older people must be respected, that older people are wiser. In Western society, there is a lot of ageism. Older people are seen as a burden on society—a “silver tsunami.” But I was brought up thinking old age was good, and so I set out to test that scientifically, and that brought me to wisdom.

TCPR: What is wisdom?

Dr. Jeste: Wisdom is a personality trait that has several components. I will sketch them out:

- Empathy and compassion. This is reflected in what we do for others.

- Emotional regulation and positivity. This doesn’t mean you have no emotions, but you have control, you don’t go from one extreme to another, and you tend to be positive much of the time.

- Self-reflection. This is the ability to look inward and say “Maybe I did something wrong, so I can do better next time” instead of blaming others.

- Accepting diversity of perspectives. This is the capacity to say “I have my strong opinions and somebody else may have strong but different opinions. I don’t agree with that person, but that’s all right.”

There are also other components like being decisive—not making a quick decision, but making a rational decision. Spirituality may be a component too, but the field is split on whether that should be included.

TCPR: Are you saying that all four of these components increase with age?

Dr. Jeste: In general, yes. But there are some old people who are really unwise, and some young people who are very wise. On psychological tests, older people tend to be better at controlling their emotions, especially negative emotions. They have better self-reflection and insight. They are more compassionate, empathic, and helpful toward others, more accepting of diverse perspectives (Jeste DV et al, Perspect Biol Med 2019;62(2):216–236).

TCPR: You are challenging the “Archie Bunker” stereotype of a prejudiced, complaining older person.

Dr. Jeste: Yes, for the average person, positivity increases with age. When you are young and you go to a party and four good things happen along with one bad thing, you only remember the bad thing. In older age, that is reversed. Older people remember the good things for a longer time and forget the bad things. There is biology behind this. An older person’s amygdala responds less to negative stimuli compared to a younger person, as seen in functional brain imaging studies (Mather M et al, Psychol Sci 2004;15(4):259–263). When people look at a smiling baby, everyone’s amygdala lights up—young and old. But when people look at, say, a gruesome car accident, a younger person’s brain lights up more.

TCPR: Are there other biological changes associated with wisdom?

Dr. Jeste: Yes. This is a simplification, but by and large, wisdom is housed in the prefrontal cortex, especially the dorsolateral, ventromedial, anterior cingulate and insula, and the limbic striatum, including the amygdala. There are changes that occur in our chemistry that are bad in some ways but good in other ways. For example, the level of dopamine in the brain goes down with age, and that increases the risk of Parkinson’s disease. On the other hand, dopamine in the striatum runs the reward system, and lower dopamine can mean less addiction, impulsivity, and dependence on the reward system. Another thing we see with age is the development of new neural networks in subcortical regions such as the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus and the periventricular region.

TCPR: Tell us about that.

Dr. Jeste: This does not happen to everyone, but if a person stays active physically, cognitively, and socially, they may continue to develop new subcortical networks as they age. Now, it is generally the wiser people who tend to stay active like this, so there is a bit of a virtuous cycle going on here.

TCPR: Why are some young people “wise beyond their years”?

Dr. Jeste: Wisdom is partly determined by genes. Like most traits, it is about 50% genetic and 50% environmental, although part of that environment is shaped by our behavior, which is partly influenced by our genes. So if somebody has strong genes for wisdom, then clearly they will be wiser from a younger age. But also, they tend to use even their experiences in young life far better than other kids. You see this from an early age. They share their toys. They don’t have as much sibling rivalry or fight as much with other kids.

TCPR: How can we improve wisdom?

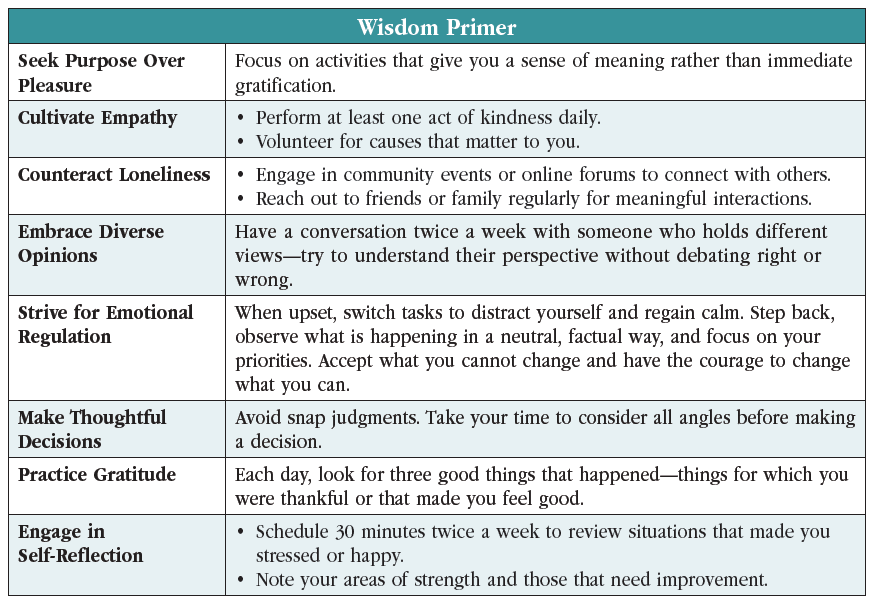

Dr. Jeste: The first thing would be self-reflection. Set aside 30 minutes, twice a week, to reflect on things that made you stressed or happy. The key is to make self-reflection a habit. Over time, you will see patterns that you can do something about. Self-reflection is a wisdom trait, and people can reflect on which traits they are strong in and which ones need more work (Editor’s note: See the table “Wisdom Primer”).

TCPR: How about empathy and compassion?

Dr. Jeste: Taking up volunteer work is one approach. Another is gratitude. We used to recommend a gratitude diary to increase that, but people got bored keeping a daily diary. So now we recommend the “three good things” approach. Think about three things that made you feel good over the past day, either things that happened to you or things that you did. If you do this every day, it becomes second nature (Montross-Thomas LP et al, Int Psychogeriatr 2018;30(12):1759–1766).

TCPR: What do you recommend for emotional regulation?

Dr. Jeste: Like the other traits, this improves through practice. One example that often gives us an opportunity to practice is road rage. We can get angry and curse at the driver, or better, try to reinterpret their behavior. What if they were rushing to an emergency? Another technique is distraction, such as by moving away from the unsettling problem and onto something else, changing the music, counting seven things around you, or recalling a positive memory.

TCPR: How can we become more accepting of diversity?

TCPR: How can we become more accepting of diversity?

Dr. Jeste: I recommend meeting people who are different from you on a regular basis, twice a week—these are people who are different in age, sex, skin color, national origin, and even political beliefs. That doesn’t mean that you argue with each other and say who is right; rather, the goal is to develop some respect for each other. You can totally disagree with them, but try to understand where their thinking is coming from. It will help you understand the basis of your own beliefs. Now, this will exclude people who are obviously sociopathic—I’m not recommending lunch with murderers and rapists.

TCPR: What role does pleasure play in all this?

Dr. Jeste: There are two types of well-being. One is hedonic well-being, which relates to pleasure due to materialistic gains. The other is eudaimonic well-being, which is associated with having a purpose and meaning in life. The goal of life is not just to make more money because even if you make more money, you will want more—so the hedonic treadmill never ends and people become even more unhappy eventually. Not only that, but hedonic well-being is associated with increased expression of proinflammatory and proviral genes compared to eudaimonic well-being (Fredrickson BL et al, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110(33):13684–13689).

TCPR: Can adversity improve wisdom?

Dr. Jeste: It depends upon how you react to the adversity. Anything is fine for the initial reaction—that is almost reflexive and often not how we want to react. What you do next is the question. In general, the Serenity Prayer is a good guide here: “Accept the things that you cannot change, have the courage to change the things you can, and have the wisdom to know the difference.”

TCPR: What stands in the way of wisdom in today’s society?

Dr. Jeste: One thing that comes to mind is loneliness. Long ago, loneliness was seen as a positive thing because it meant you were closer to God. It came from the word “oneliness.” Now there’s an epidemic. Between 2015 and 2017 the average lifespan in the US fell for the first time since the 1950s, and it has fallen more since then because of COVID. It fell earlier because of conditions that are related to loneliness: suicides and opioid-related deaths. These are “deaths of despair.”

TCPR: Has that affected the elderly more or the younger population?

Dr. Jeste: Both are affected—but there is some surprising information here. In the past 20–30 years, younger adults’ mental health has gone down while that of older people has gone up. We saw this during COVID. We expected the pandemic to be harder for older adults, who are more vulnerable to illness and have trouble with technology, but younger people were several times more likely to develop anxiety and depression during COVID than older people (Vahia IV et al, JAMA 2020;324(22):2253–2254).

TCPR: There’s a related epidemic of burnout.

Dr. Jeste: Yes. Suicide rates are on the rise for clinicians and medical students. There are more stresses for younger clinicians than there were when I started out. The healthcare system is broken, competition is higher, and providers have less power to do what is right for the patient.

TCPR: How can younger physicians reduce burnout?

Dr. Jeste: Empathy and compassion, including self-compassion. Clinicians are so busy helping others that they don’t take the time to learn how to be compassionate toward themselves. Often they are self-critical and unforgiving of themselves. Be kind to yourself, just as you want to be kind to your friends. There are common emotions we all have as clinicians—guilt when something goes wrong, embarrassment when we make an error—and we need to teach medical students how to regulate these emotions.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Jeste.

Dilip V. Jeste, MD.

Dilip V. Jeste, MD.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)