Autism in Adults

TCPR: How do you diagnose autism in adults?

Dr. Feder: The DSM-5 criteria apply to children and adults, but they require some skill so they aren’t interpreted too broadly. The first criterion refers to “deficits in social communication,” but you see that in a lot of disorders. To focus in on autism, look for the person’s appreciation of nuance in their moment-to-moment interactions.

TCPR: How does that look in the room?

Dr. Feder: If I interrupt an autistic person, they often do not react, perhaps as if they are uncertain how to respond. Or they might call me on it but in a brusque manner, like saying “That was rude.” I also look for whether they mirror me. Do they respond when I smile? If I get up at the end of the appointment, do they get up?

TCPR: How do you distinguish these behaviors from other disorders that cause social deficits?

Dr. Feder: If there’s a friendly informant in the room, I’ll ask respectfully “How well do they read other people’s intentions?” That can earn a false positive if the patient has depression or anxiety, so look for long-term patterns. People with borderline personality, anxiety, and mood disorders are often hypersensitive to those nuances, seeing rejection or animosity when there is none. Autistic people tend to be under-responsive to these nuances.

TCPR: So they’re not exactly misreading you. They are under-reading you.

Dr. Feder: They can have a high threshold for reading people’s emotions and intent, so if something is subtle and below that threshold, they might not pick up on it. But if they are faced with more intense expressions, they may misread it, and often in a negative way. We see similar patterns in untreated ADHD, where people miss subtle cues and misread neutral ones for negative. It’s the same with eye gaze. Some autistic people naturally avert their gaze. To differentiate that from depression or anxiety, ask about their experience of eye gaze. Has it always bothered them? In what situations?

TCPR: Tell us about the next criterion: “restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities.”

Dr. Feder: Autistic people often talk extensively about their unique perspectives, anything from politics to history, electronics, or internet groups. They may tell the same story repeatedly. They may speak in a formal, “professorial” manner. Their inflection may be reduced, or they may speak with a tone or rhythm that seems out of place, as if it were borrowed from a movie they saw. Another area where you may see restriction is in their understanding of emotions.

TCPR: How does that present?

Dr. Feder: They often focus only on prominent emotions. For instance, if their spouse is mostly angry, but also scared and hurt, they may respond only to the anger. Or when asked “Why did your boss say that your work needs to improve?” they may respond “He’s mad because I didn’t meet the deadline.” To that, you could ask “Do you think there’s anything else he might be feeling?” Encourage the person to consider other emotions going on to help them plan a more effective response.

TCPR: Is there a rigidity in their thinking?

Dr. Feder: I see it as focused thinking with relative difficulty entertaining additional possibilities. They may seek confirmation of their personal political or religious ideas. Concrete thinking can be a problem for autistic people who misunderstand a metaphor. For example, if they hear: “I can’t stand this,” they might respond with: “So sit down.” Even so, while neurotypical people are prone to groupthink, neurodivergent people often see things from perspectives that add to our understanding (Editor’s note: Autism is a form of neurodivergence).

TCPR: The criteria also mention stereotyped movements.

Dr. Feder: Yes. These usually have a purpose. They may be calming or interesting or pleasurable. That’s important to understand in treatment. Don’t try to suppress them just because they appear unusual. Likewise, the insistence on sameness and routines usually reflects their need for stability in a world that feels unpredictable to them, where the social rules are not always explicit or the sensory environment is overwhelming.

TCPR: Do they experience the sensory world differently?

Dr. Feder: Yes. Certain foods or textures or smells may bother them (eg, clothing tags), or they may seek out strong smells or flavors, or certain fabrics. The DSM criteria also mentions their focus on parts of objects versus the whole. That is not necessarily a problem. Appreciate their fascination with light and shadow, or with the mechanics of an elevator pulley. This ability to see things through a different lens often leads to innovation.

TCPR: What are the best tests to identify autism?

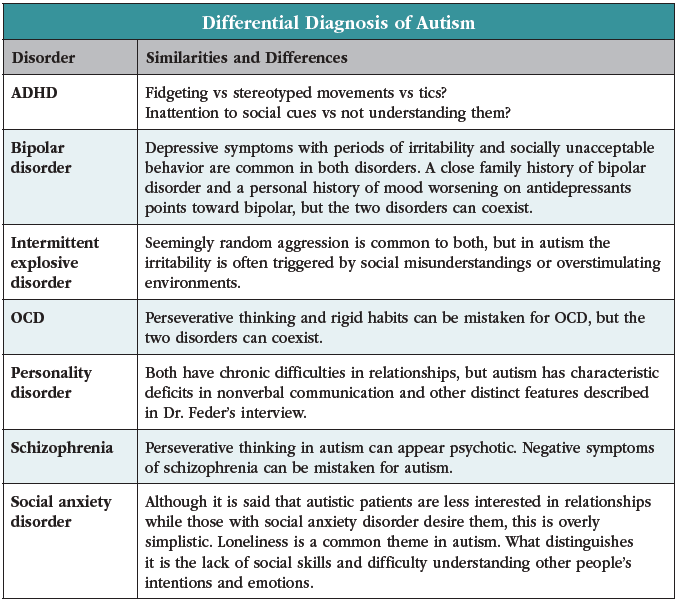

Dr. Feder: The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2) is called a gold standard, but it requires training and certification to administer, so it is mostly used by psychologists who specialize in testing. Another option is the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Both of these are validated in adults, but neither should be used alone. These measures can miss subtle autism, or they can overdiagnose. You need an experienced clinician and good collateral information to optimize accuracy (Gwynette MF et al, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019;58(12):1222–1223) (Editor’s note: See table).

TCPR: Are there simpler instruments?

Dr. Feder: There are online instruments such as Simon Baron-Cohen’s Adult Asperger’s Assessment. This is free for professionals at the Autism Research Center (www.tinyurl.com/mspjk6nf), but Wired Magazine has an easier-to-use public version (https://www.wired.com/2001/12/aqtest/). Independent examination did not find it particularly reliable (Jones A et al, J Autism Dev Disord 2022 (Epub ahead of print)). I’ve seen people take it more than once and get different “answers” about their likelihood of having Asperger’s.

TCPR: Do you see autism as a black-and-white diagnosis or a spectrum?

Dr. Feder: We are moving away from the categorical, medical model in autism. Instead of a diagnosis that needs treatment, it’s seen as a natural form of neurodiversity.

TCPR: Do you mean we don’t treat autism?

Dr. Feder: Not in the sense that we do with, say, depression. People with autism benefit from individualized support for autistic traits, and also from treatment of co-occurring conditions such as anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and sensorimotor differences.

TCPR: Tell us more about how you approach autism in treatment.

Dr. Feder: I favor a relationship-based approach that helps people connect with others in meaningful ways so that they can learn, problem solve, and live more happily and safely. Autistic adult advocates and a growing body of research are moving away from applied behavioral analysis, a treatment that has dominated for 40 years. Today this treatment is viewed as not very effective and with little applicability to adults or those with milder autistic features.

TCPR: Is there a pharmacotherapy approach to autism?

Dr. Feder: Autism is one area where FDA approval is not a helpful guide. Risperidone and aripiprazole are FDA approved for irritability associated with autism in kids. These carry significant risks and do not treat core symptoms of autism. Moreover, autistic individuals often have co-occurring depression, anxiety, ADHD, sleep problems, and other difficulties that are triggering irritability or contributing to problems with social communication and other areas of function. You’ll want to address these before jumping to antipsychotics.

TCPR: How do you proceed?

Dr. Feder: First, try a nonpharmacologic approach. Look for what is triggering the irritability and intervene there, like with sensory problems or communication difficulties. If you must use a medicinal treatment, start with a calming supplement like valerian or lavender and then move to milder symptom-focused medications (eg, stimulants for concentration or SSRIs for anxiety) before you go to more potentially metabolically problematic and neurotoxic medications. And even when you’re using second-generation antipsychotics, we recommend the ones that have fewer metabolic risks than risperidone and aripiprazole, like ziprasidone and lurasidone.

TCPR: What supplements do you start with?

Dr. Feder: That depends on the presenting symptom. For irritability we might try 500–1000 mg/day of omega-3 fatty acids or 1–3 mg of melatonin in the daytime (Mazahery H et al, J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2019;187:9–16). For anxiety we might try lavender oil (Silexan 80–160 mg/day) (Editor’s note: See the August 2020 issue of The Carlat Psychiatry Report on use of lavender in anxiety). For insomnia we might try melatonin 1–3 mg given 90 minutes before bed (Xiong M et al, Neuropediatrics 2023;54(3):167–173).

TCPR: I understand medications can treat symptoms like aggression, depression, and inattention. Do any meds modify autistic traits?

Dr. Feder: Not yet. Oxytocin had promising data but did not pan out. With meds, a reasonable goal is to help someone stay calm and regulated so they’ll have an easier time forming relationships. Treat ADHD and other co-occurring conditions. When people are more attentive and less depressed or anxious, they relate, communicate, and learn better.

TCPR: What options do parents have as their autistic child approaches adulthood?

Dr. Feder: Autistic people are presumed competent when they turn 18, but this can lead to trouble if they order credit cards, make medical decisions, or get tricked into committing crimes for “friends.” One solution is to place them in conservatorships where conservators, usually parents, decide everything from where the person lives to whom they can date and marry. However, there is growing recognition of the autonomy of developmentally diverse people through a shared decision-making approach where the individual makes the decisions but has agreed to have assistance. The relationship is like an advisory board for a nonprofit organization. The person retains final say.

TCPR: Eventually their parents grow older or pass away. What can we do then?

Dr. Feder: This is a big problem. On the one hand, that protective family home can keep people from living independent lives. On the other hand, there are a lot of autistic people who would make some pretty poor decisions out on their own. They let people take advantage of them and get into abusive relationships. Group homes are the most common solution, but they have problems.

TCPR: Like what?

Dr. Feder: Group homes have different levels, and a lot depends on that. A “level 4” will have lots of violent people and requires more staff. Often chemical or physical restraints are used. But even at lower levels of intensity, it is not a fun way to live, and care can be limited. If you have been waiting to go to the doctor for three months and someone at the group home has an emotional meltdown and the staff can’t take you, you miss your appointment. Same goes for fun outings. For wealthier families, “supported living” is an option. They can rent or buy a condo where the patient can live alone but still have support staff checking on them.

TCPR: What supports are available for college students on the spectrum?

Dr. Feder: There are specialty companies offering “helicopter” services where someone will check in on the student and make sure they are going to class, doing their homework, taking showers. I think these are helpful if the family can afford them, but sometimes the young person resents them. For most families, disability services are a good place to start. The Organization for Autism Research has a good guide for this (www.researchautism.org/resources/finding-your-way/).

TCPR: Are there support services on the job?

Dr. Feder: Autistic people have a lot to offer but typically need support to succeed. Some corporations have programs for them, including Amazon, Microsoft, and Google. The company also gets a tax credit. This is an area where the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (www.ASAN.org) and other advocacy organizations are working to improve opportunities for autistic individuals.

TCPR: Are there areas where autistic people excel?

Dr. Feder: In every field, ie, beyond engineering, and including theater. Some autistic individuals are charismatic on the stage with an encyclopedic memory, making them very consistent performers. We also see autistic golfers who have a brilliantly repeatable swing. They may still have great difficulty in nuanced social situations at work or in relationships. But it’s important not to tokenize autistic people by assuming they all have a special ability. Some do and some do not. Find out what is meaningful to the person, what their goals are, and how to help them achieve those goals and obtain relief from suffering.

TCPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Feder.

Joshua D. Feder, MD.

Joshua D. Feder, MD.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)