Taking a Sexual History With Children and Teens

Talking about sex with our child/adolescent patients gives us insight into their development and identity and allows us to better support them. This article covers the foundations of taking a sexual history, focusing on language, content, and consent.

We don’t ask often enough, and that has consequences

Many clinicians skip the sexual history. One Canadian study found that only one-third of adolescents admitted to hospitals were asked a sexual history, even though we know adolescents with mania and/or ADHD have higher rates of risky sexual activity (Harrison ME et al, J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018;27(2):122–129). Sex and sexuality are sources of trauma that negatively impact our patients’ lifelong mood, cognition, and behavior. Women who experienced childhood sexual abuse are three to five times likelier to develop depression as adults (Olafson E, J Child & Adolesc Trauma 2011;4(1):8–21).

Ask all children about the possibility of sexual trauma and sexual activity. Some situations merit a closer look, including pubertal children, pre-pubescent kids engaging in sexual play, or reports of inappropriate sexual behavior.

Initiating the conversation: “Let’s talk about sex”

It can be awkward to talk with kids and adolescents about sex, on both your part and the patient’s. You may feel uncomfortable with the language needed to discuss sex directly and accurately or worry that the conversation might inappropriately cross boundaries. Ease these concerns by setting the tone and expectations for these conversations with children and their families. See the box for more details.

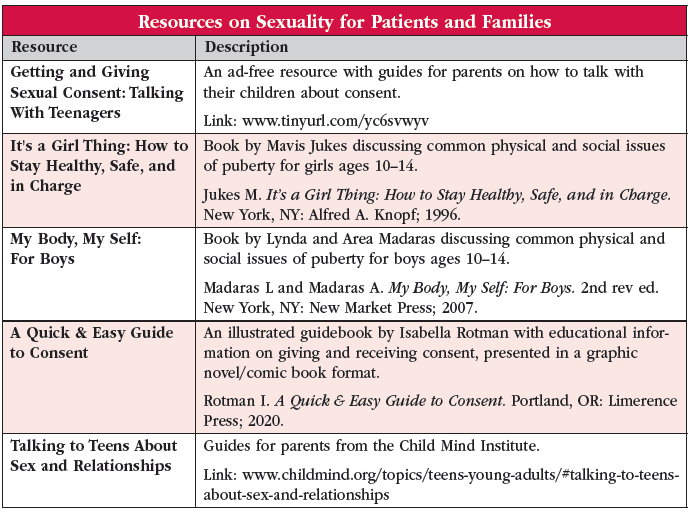

Use a relaxed tone while acknowledging that talking about sex can be uncomfortable: “I ask all my patients about sex, and for some people, it can feel awkward. By talking with you about sex, I want to make sure you are safe and healthy.” Remind patients that they can ask you any questions about sex now or in the future. Let them know that you will bring up sex and relationships throughout your time working with them. For additional conversation guides, see the “Resources on Sexuality for Patients and Families” table on page 10.

Meet separately with your patient’s guardians. Let them know that you will be talking with their child about sensitive topics including sex and trauma. Inform parents (and patients) that those conversations are confidential unless there is an immediate risk: “When I meet with your child, our conversation will be confidential. The only reason I would break that confidentiality is if there is any immediate risk to their safety or someone else’s safety, or reports of abuse.”

What do you ask in a sexual history?

Our focus when taking a sexual history is multi-fold: to assess gender identity, sexual identity, sexual interest/expression/pleasure, and of course history of trauma, violence, or exploitation.

Pre-pubescent patients

With pre-pubescent patients, ask about the child’s experience of their gender and assess for sexual violence/trauma. Key observations and questions:

- Assessing gender for pre-pubescent kids begins primarily via observation and guardian reports. Gender formation begins in early childhood and continues into adulthood.

- “Some people are boys, girls, or something else. What about you?”

- “Has anyone ever touched your body in ways you did not want to be touched?”

- “Have you ever felt uncomfortable or unsafe around other people in your home, at school, or at any of your activities?”

- “Has anyone ever asked you to touch them in private areas?” (If the patient discloses any sexual misconduct/abuse, establish how to keep the patient safe, but do not try to obtain all the details, as this will be done by Child Protection Services. Avoid multiple people asking the patient the same questions.)

Pubescent patients

With pubescent children, cover the same areas and also ask about sexual practice. Acknowledge that the topic of sex can feel awkward and that patients do not have to answer if they are uncomfortable. Before jumping into questions about sexual practice, ask about romantic relationships: “Do you have any crushes? Anyone you are seeing/dating?”

From there you may ask, “Are you sexually intimate with others? What about with yourself?” In addition to asking about masturbation, you can get more detail about sex with other people using the language and question examples in our “The Five Ps of a Sexual History” table as a guide. Regardless of whether patients answer yes or no to being sexually intimate with others, you should ask the same questions as with younger children regarding potential sexual abuse. Some people have little or no sexual interest. Explore this too for prior trauma, depression, etc. or natural diversity.

Teach consent along the way

Check with teens whether they know the age at which they can consent to sexual activity and talk about how to give and ask for consent. Model this throughout your visits with your patients, asking permission to discuss sensitive topics and opening an ongoing dialogue about consent and healthy boundaries. Taking these steps reduces the risk of future abuse (Santelli JS et al, PLoS ONE 2018;13(11):e020595).

To assess how much a patient knows about consent, ask the following:

- “Have you ever learned about consent?”

- “What does it mean to you?”

For pre-pubescent children, teach about consent by discussing non-sexual forms of physical contact:

- “If you want to give a hug to a friend, what do you do?”

- “What do you do if someone touches you and you don’t want to be touched?”

For patients who are sexually active:

- “Sex can make us feel a lot of different ways; how do you feel about your sexual experiences?”

- “Do you enjoy having sex?”

- “How do you feel after?”

- “Do you ever feel pressured to have sex or perform sexual acts you don’t want to?”

- “Are there sexual acts you want to perform but your partner doesn’t?”

- “How does sexual contact with your partner usually begin?”

- “Do you ever say no to sexual contact with your partner?”

- “How would they respond if you said no?”

- “Do they ever say no?”

- “How would you respond if they said no?”

Find opportunities to educate patients about their right to say no to any type of physical contact (and their partners’ right to say no).

Key Points for Taking a Sexual History With Children and Adolescents

- Ensure privacy by making space for the patient to share apart from guardians or other people

- Maintain a gentle and confident tone to normalize topics

- Attune to the patient’s developmental stage, language, and affect

- Discuss that you will have to breach confidentiality if the patient indicates risk to self or others, or signs of abuse/neglect

- Estimate the Tanner stage without invasive examinations (www.tinyurl.com/2p8vdrzb)

- Establish rapport and therapeutic relationship before discussing sensitive subjects

- Ask permission to pose sensitive questions (“Can I ask you some questions about your sexual activity?”)

- Use short and clear questions (“Have you had sex in the past three months?”)

- Respect the patient’s right to decline to answer

- Don’t put words in the patient’s mouth by asking leading questions (“You’re not having sex, are you?”)

- Use inclusive terms (eg, partner) to avoid making assumptions about the patient’s sexuality and gende

CARLAT VERDICT

Talking about sex builds trust. Normalize that sex is a part of life even though it can be uncomfortable to discuss. Let patients be in charge of how much they share with you and provide them with tools to maintain healthy boundaries.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)