Managing Substance Use in Older Adults

Louis Trevisan, MD.

Louis Trevisan, MD.

Clinical professor of psychiatry, Creighton University School of Medicine, Omaha, NE; associate professor of psychiatry, adjunct, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT.

Dr. Trevisan has no financial relationships with companies related to this material.

CGPR: Please tell us about yourself and the work that you do.

Dr. Trevisan: I’m a professor of clinical psychiatry at Creighton University and the director of the substance use disorders (SUDs) treatment division. I’m also an associate professor at Yale where I’ve spent the past 30 years primarily working at the VA in SUDs and in geriatrics. I’ve worked in ambulatory detoxification, stabilization, and inpatient rehab units.

CGPR: How do you approach screening for SUDs in older adults?

Dr. Trevisan: Clinicians often don’t ask older people about substance use because they can’t imagine that somebody their grandmother’s age might drink a bottle of wine every night or take their husband’s oxycodone (OxyContin) surreptitiously. When patients present with any mental health problems, I ask “Are you using any substances, such as alcohol, or taking any extra prescribed medications?” If they say yes, I follow up with screening tools.

CGPR: Which screening tools do you find helpful for alcohol use disorder (AUD)?

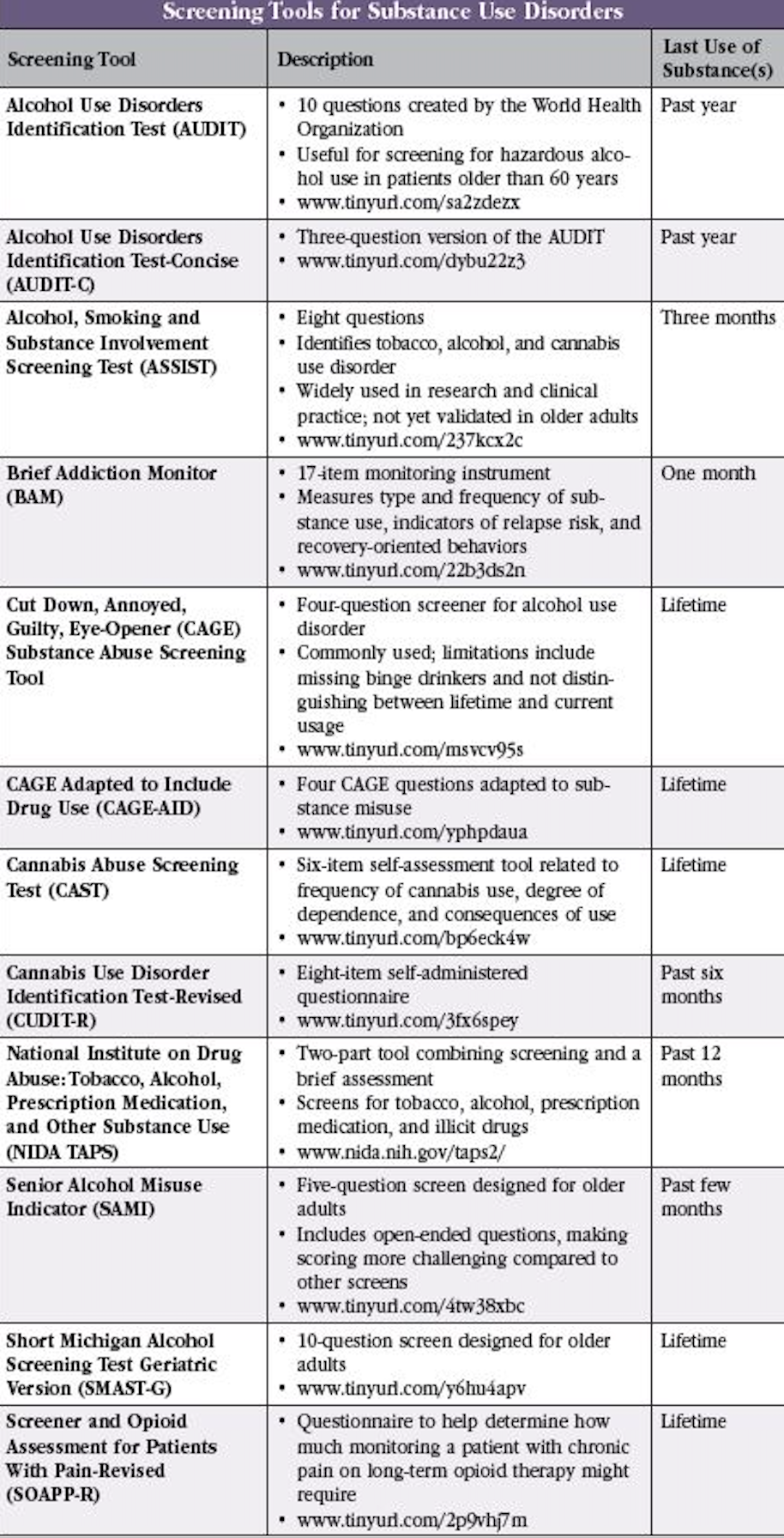

Dr. Trevisan: I combine the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Concise (AUDIT-C) with the Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye-opener (CAGE) questionnaire. I then ask “Has this ever been an issue, not just now?” There’s also the Short Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (SMAST) and a geriatric version (SMAST-G; www.tinyurl.com/y6hu4apv). It’s a 10-question screener with yes/no answers that patients can complete while they’re waiting to see you (Editor’s note: See “Screening Tools for Substance Use Disorders” table below for more information).

CGPR: What do you use to screen for opioid and other substance use?

Dr. Trevisan: For opioid use or pain medication misuse, I like the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) (www.tinyurl.com/477hnu73). There’s also the National Institute on Drug Abuse: Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription medication, and other Substance use (NIDA TAPS) tool, a four-item screen for tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and non-medical use of prescription drugs (www.nida.nih.gov/taps2/). This tool assesses how often patients have used tobacco products, had more than five drinks (for men) or four drinks (for women) in a day, misused prescription medications, or used illicit substances in the past 12 months. I used to use screening tests for tobacco, but now I just ask people about tobacco and vaping. I also ask about cannabis and advise people not to smoke it, but I generally don’t use a screening tool. A short six-item self-administered cannabis use disorder screening tool does exist, however, called the Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) (www.tinyurl.com/jn49kcz4).

CGPR: The DSM-5 criteria for SUDs may not be relevant to older adults due to changes in physiology and role obligations in older age. What should clinicians keep in mind when diagnosing an SUD in older adults?

Dr. Trevisan: SUDs are not easily diagnosed with the usual DSM criteria in older adults, and there are no specific diagnostic criteria for SUDs in old age. Older adults may not be involved in the same activities, so you may not see functional impairment at work, as an example. You may not see family problems if the patient lives alone; many older adults are isolated, especially since COVID. They may not have a DUI; they may not be seeking out heroin on the street; however, they may be misusing their medication. You may need to ask them to bring in their medications or have a family member corroborate what’s going on. Older adults may also have multiple medical problems and a higher incidence of chronic pain, so their symptoms may manifest somatically. Remember that almost anything medical could also be due to substance use. You don’t want to say “That’s just age related” or ascribe changes in mental status to medical problems without assessing for substance use. For cognitive issues, you always want to ask about benzodiazepines and opioids; for complaints of constipation, you also want to ask about opioids.

CGPR: What’s the relationship between drinking alcohol, cognitive performance, and the development of dementia?

Dr. Trevisan: Drinking alcohol causes global damage. It can greatly influence a person’s ability to form memories, can lead to blackouts, and impairs the speed of information processing. When information processing and overall brain functioning is impaired, patients develop worsening cognitive and physical functioning (eg, balance problems and falls). Alcohol mimics GABA’s increasing sedating and anxiolytic effects on the brain. It also inhibits glutamate at the NMDA receptors, upregulating NMDA receptors with prolonged use. When alcohol is taken away, the neurons become very excitable, which can lead to acute withdrawal. Cognitive performance is also affected by neuronal excitotoxicity. Over time, regular alcohol use can cause encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s psychosis, characterized by confabulation. There’s an increasing amount of literature suggesting that any amount of alcohol can be damaging to the brain (Welch KA, BMJ 2017;357:j2645).

CGPR: How do you speak with patients about the harmful effects of alcohol on the brain?

Dr. Trevisan: Older adults seem to be more likely to follow the doctor’s advice, and they do better when their doctor uses motivational approaches. I generally start with a statement such as “I’m concerned about your drinking.” Patients with AUD don’t need to be confronted and told that they shouldn’t drink. However, they do listen to medical advice and to suggestions that alcohol is bad for them in terms of their health and ability to lead a normal life as they age. It can be a brief intervention—such as 15 or 20 minutes in a session followed by a return visit—or a care coordinator can call them and see how they’re doing.

CGPR: What are the dangers of cannabis use in older adults?

Dr. Trevisan: Older adults can experience rapid changes in their mentation due to smoking, using edibles, or vaping cannabis. They are more likely to misuse cannabis, not knowing how potent it is. Nowadays, cannabis is extremely potent and all it takes to have an effect is a tiny piece of a bud in a vape. The use of cannabis has been associated with an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and short-term memory deficits (Preuss UW et al, Front Psychiatry 2021;12:643315; Kroon E et al, Curr Opin Psychol 2021;38:49–55). Acute cannabis intoxication can cause tachycardia, increased blood pressure, increased respiratory rate, psychosis, panic attacks, dry mouth, ataxia, and slurred speech. Over a long period of use, cannabis can cause cognitive difficulties, including impaired learning. It can also cause depression and motor incoordination.

CGPR: When you speak with older adults about cannabis use, what seems to work? How do you respond when they claim that taking a gummy at night is the only thing that helps them sleep or removes their anxiety?

Dr. Trevisan: Honestly, I’m not sure I have found success. While cannabis has become recreationally available and medically used, there are insufficient data to support its efficacy in treating any mental illness, especially in older adults. The best we can do is provide what limited information we have in terms of potential effects and advise our patients not to use it. If patients use cannabis products, I caution them to be careful. We know that saying no doesn’t work. I try to educate them about the possibility of interactions with their prescription drugs since we don’t know how cannabis and prescription medications interact. Some people will continue to use—I’ve had older patients use cannabis in clinic while in treatment for another SUD. We used to terminate treatment when patients had positive toxicology screens, but now we don’t, even if patients have cannabis in their urine. Instead, we use a harm reduction approach. You want to encourage patients to come back, field their questions, and try to update them. Hopefully, sooner or later they will be ready to decrease their cannabis use.

CGPR: What is considered medication misuse in older adults?

Dr. Trevisan: Most older American adults take multiple medications, often prescribed by multiple specialists. Many do not take their medications as prescribed—it is estimated that between 12% and 15% of older adults regularly seeking medical care misuse prescription medications (Basca B, Prevention Tactics 2008;9(2):1–8). The main culprits are medications prescribed for pain, sleep, or anxiety (eg, opioids and benzodiazepines). Patients may take an extra alprazolam (Xanax), forget to take their anticonvulsant medication, or skip their antidepressants (or double up on them). They may notice that they feel really good and get a great night’s sleep when they take oxycodone, and then take an extra one—this constitutes medication misuse and can lead to more serious problems.

CGPR: How can clinicians minimize medication misuse in older adults?

Dr. Trevisan: Mayo Clinic Proceedings has a medication action plan to manage polypharmacy. It outlines deprescribing and addresses opioids and benzodiazepines in a separate section, as well as other classes of medications (Hoel RW et al, Mayo Clin Proc 2021;96(1):242–256). It recommends clinicians assess drug-drug and drug-disease interactions; identify non-beneficial therapy and simplify; and identify high-risk therapy and reconsider. It also recommends a motivational interviewing–style approach toward medication reconciliation. Clinicians should assess for adherence and barriers. If a medication is not needed, they should eliminate it. Although it seems like a lot of work, older adults get a lot of mileage out of such a medication action plan. An additional resource for deprescribing algorithms, with excellent materials for both clinicians and patients, can be found at www.tinyurl.com/53nxauxw.

CGPR: Thank you for your time, Dr. Trevisan.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)