Who's Who? A Review of Delusional Misidentification Syndromes

Adrienne Grzenda, MD. Clinical Assistant Professor of Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine and Olive View UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA. Dr. Grzenda, author for this educational activity, has no relevant financial relationship(s) with ineligible companies to disclose.

Your new patient is a 30-year-old male with schizophrenia, disorganized type. His mother comes to the unit to visit, but he refuses to meet with her. He tells staff that the woman looks and sounds like his mother but is an impostor. His mother visits again two days later, and he demands that staff not allow her on the unit, saying “That lady is trying to trick me, but I don’t know who she is, and I don’t want her visiting anymore!”

Patients with delusional misidentification syndromes (DMS) are some of the most fascinating patients you’ll treat in your career. These syndromes are defined as psychotic phenomena involving a mistaken belief that a familiar person or object has been replaced or transformed. While not specifically mentioned in the DSM-5, they are usually categorized as delusional disorders. In this article we will review these perplexing conditions, including their workup and management.

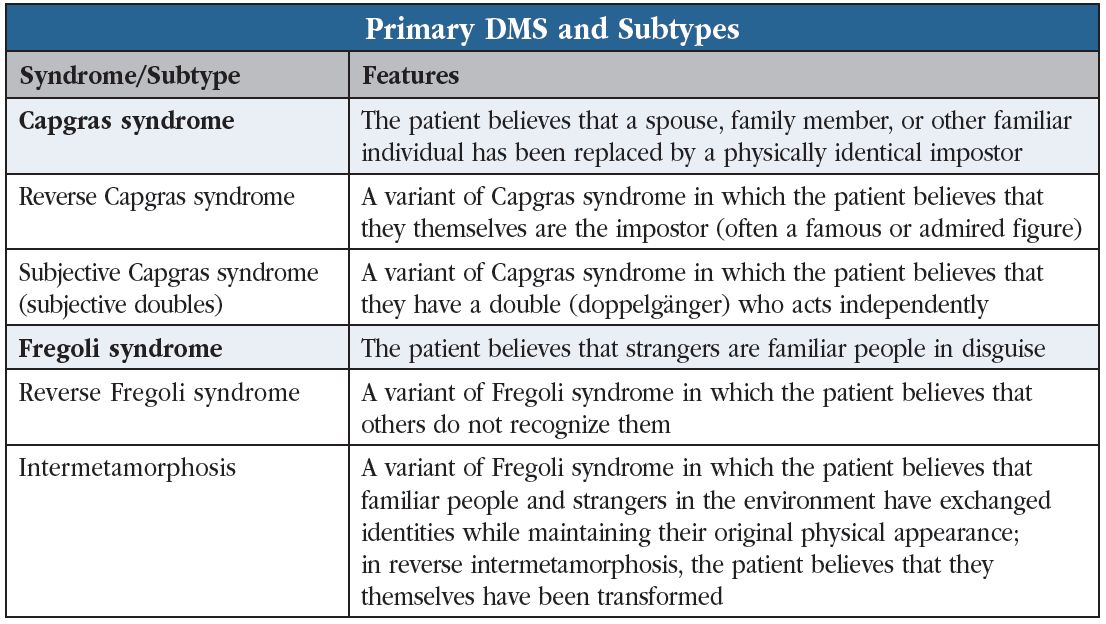

Types of DMS

Capgras syndrome and variants

The most common and best-characterized form of delusional misidentification is Capgras syndrome, where individuals believe that their loved ones have been replaced by identical-looking impostors. The delusion was named after Joseph Capgras, a French psychiatrist who described the syndrome in a study he published in 1923.

Capgras syndrome appears most frequently with psychotic illnesses (56%), but dementias, delirium, traumatic brain injuries, and other medical conditions account for a large proportion (43%; Pandis C et al, Psychopathology 2019;52(3):161–173). When the underlying illness is a psychiatric disorder, patients tend to be younger at syndrome onset and predominantly female. They experience higher rates of paranoia, mood symptoms, auditory hallucinations, and aggression, and the impostor is typically a parent. In contrast, when the underlying illness is dementia, delirium, or another medical condition, patients tend to be older and report more visual hallucinations, and the impostor is typically the spouse or an inanimate object. An unusual variation of Capgras is subjective Capgras syndrome, in which patients believe that doppelgängers or doubles of themselves exist and act independently (see “Primary DMS and Subtypes” table).

Fregoli syndrome and variants

Fregoli syndrome is the opposite of Capgras syndrome. Instead of believing family members are strangers, patients with Fregoli syndrome believe that strangers they meet are familiar people in disguise, like a spouse or friend, typically with the intention of persecuting them. A variant is intermetamorphosis, in which the individual believes that familiar people and strangers swap identities while maintaining their original appearances. Alternatively, the individual may believe that people cannot recognize them (reverse Fregoli syndrome).

Others

Truman Show delusion. In this delusion—named after the 1998 movie—a person believes that their entire life is a staged reality show that is broadcast for others’ entertainment. For a fascinating description of an example, listen to the This American Life podcast episode called “Seeing Yourself in the Wild.”

Cotard syndrome. People with Cotard syndrome believe they are dead or that parts of their body are missing or putrefied.

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of DMS vary widely, largely due to inconsistent syndrome definitions and sparse research, but Capgras syndrome is by far the most frequent presentation, followed by Fregoli syndrome. Overall, about 14% of patients with psychiatric diagnoses experience Capgras syndrome, but the rate ranges from 8% to 50% depending on the underlying diagnosis. The risk is highest among individuals with schizophreniform and brief psychotic disorders (Salvatore P et al, Psychopathology 2014;47(4):261–269).

What causes DMS?

We don’t understand the pathology underlying these syndromes in most patients. However, in cases where patients have underlying brain lesions, these lesions typically occur in the bifrontal and right hemispheric areas of the brain (Darby R et al, J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2016;28(3):217–222). Impaired connectivity between the temporal lobe regions involved in identifying faces and objects, and the limbic system areas that control emotions and beliefs, may contribute to these syndromes as well (Coltheart M et al, Annu Rev Psychol 2011;62:271–298). The individual can identify someone or something but cannot attach the appropriate emotional reaction. The familiar face no longer “feels right,” leading to the conclusion that the person or object must be an impostor. Genetic vulnerability contributes to the risk, given that 50% of patients with these syndromes have a family history of psychosis (Kimura S, Biblioteca Psychiatric 1986;(164):121–130).

Assessment and management

As with any unusual presentation of psychosis, we should first do a standard workup to rule out medical or neurological causes. However, in most cases, the underlying issue is a primary psychotic disorder.

In your interviews with these patients, make sure to ask focused questions about whether they are thinking about harming others. About 60% of patients with these syndromes have physically attacked someone in relation to the misidentification (Silva JA et al, Psychopathology 1994;27(3-5):215–219). Anger and delusions involving persecution, spying, and conspiracy are especially associated with violence. On the other hand, Cotard syndrome is associated more with a risk of suicide than homicidal urges (Bott N et al, Front Psychol2016;7:1351).

Treatment usually involves antipsychotics, and clozapine is particularly effective even when the underlying etiology is neurological. One review described remission rates of 60%–70% with antipsychotics in general (Pandis et al, 2019), but there have been few high-quality studies of treatment outcomes. If there is underlying depression or bipolar disorder, add antidepressants or mood stabilizers as needed. Case reports have described successful treatment with electroconvulsive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. However, many patients’ delusions remain fixed despite multiple trials of medications and other interventions. We don’t know why some patients improve with treatment while others don’t.

Your patient agrees to start clozapine and reaches a dose of 300 mg daily. After two weeks on this dose, his mother visits again, and she is delighted to hear her son greet her with “Hi, Mom! I missed you.”

Carlat Verdict

Capgras Syndrome, ie, the belief that a loved one has been replaced by an impostor, is the most common delusional misidentification syndrome, but you might encounter several other subtypes. They occur among patients with psychiatric as well as neurologic and medical conditions, so be sure to complete a thorough work-up. Clozapine appears helpful even when the underlying cause is neurological.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2026 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)