QT Intervals in Psychiatric Practice

Paul Barkopoulos, MD. Clinical Assistant Professor, Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine and Olive View UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA.

Victoria Hendrick, MD. Editor-in-Chief, The Carlat Hospital Psychiatry Report; Chief, Inpatient Psychiatry, Olive View UCLA Medical Center.

Dr. Barkopoulos and Dr. Hendrick, authors for this educational activity, have no relevant financial relationship(s) with ineligible companies to disclose.

As psychiatrists, we constantly face the reality that many psychiatric drugs affect cardiac conduction. While psychotropics carry a variety of possible cardiac side effects, in this article we will focus on QT interval prolongation.

What is QT interval prolongation, and why are we concerned about it?

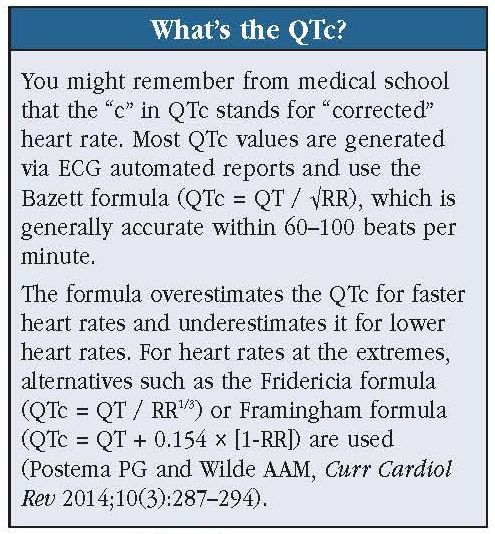

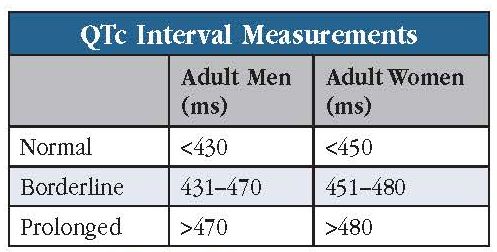

The QT interval represents the time it takes for the heart ventricles to contract and relax. Since heart rate variations affect this measurement, we typically look at QTc intervals, where the “c” stands for “corrected” (see “What’s the QTc?” sidebar). Normal QTc intervals are <430 ms for men and <450 ms for women (see “QTc Interval Measurements” table).

We worry about prolonged QTc intervals because they increase the risk of abnormal heart rhythms like torsades de pointes (TdP). Translating to “twisting of the points,” TdP is a form of ventricular tachycardia in which the QRS complexes appear to twist around the isoelectric line (see “Rhythm Strip of Prolonged QT Interval and Torsades de Pointes” figure). Most cases terminate spontaneously, but some progress to potentially deadly ventricular fibrillation. The risk of TdP increases several-fold with QTc intervals >500 ms (Trinkley KE et al, Curr Med Res Opin 2013;29(12):1719–1726).

Which patients are most at risk?

Patients at most risk are those over age 65, female, and/or with a history of heart disease (see “Risk Factors for QT Prolongation/TdP” table for more risk factors). Congenital long QT syndrome places patients at significant risk, but this condition is rare, occurring in only one out of every 5,000–7,000 patients. Additional risk factors include acute illnesses (eg, renal failure), electrolyte imbalances (low potassium, calcium, or magnesium), bradycardia, and concurrent use of more than one QT-prolonging drug. Just one additional factor might push a patient into the at-risk category.

To identify high-risk patients, we obtain vital signs and baseline labs (electrolytes, hepatic panel, CBC) and review all prescribed medications. We correct modifiable risk factors like hypokalemia and, whenever possible, eliminate concurrent QT-prolonging medications.

Which medications are likely to significantly prolong QT intervals?

The most notorious QT-prolonging non-psychotropic meds are antiarrhythmics, antibiotics, antihistamines, antiemetics, and antivirals (see “Top QT-Prolonging Non-Psychotropic Meds” table). Diuretics like furosemide increase the risk due to their tendency to produce hypokalemia. There is a helpful registry that categorizes medications by their risk of QT prolongation available at the website www.CredibleMeds.org.

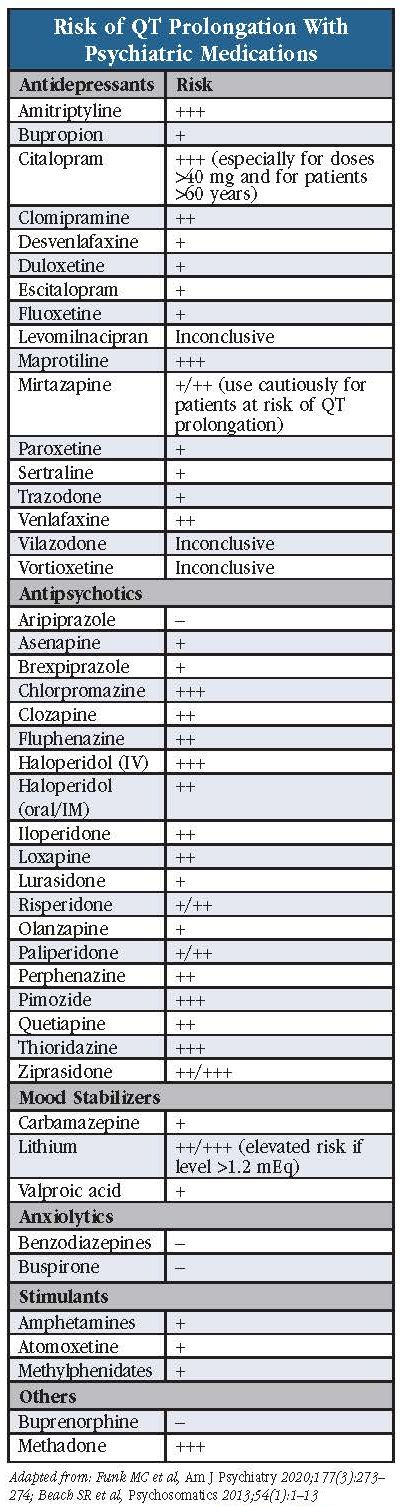

Among psychiatric meds, thioridazine, chlorpromazine, ziprasidone, pimozide, methadone, IV haloperidol, citalopram (>40 mg/day), and tricyclic antidepressants produce the most worrisome QT prolongation. In overdose, many additional medications have the potential to prolong the QT interval.

How do we manage patients on QT-prolonging psych medications?

Prior to beginning a QT-prolonging medication like ziprasidone, we obtain a baseline ECG. We then obtain another ECG once the drug reaches steady state (ie, after five half-lives). Certainly, ECGs should be repeated in patients with new-onset palpitations, syncope, chest pain, or shortness of breath. Also, we obtain baseline electrolytes and repeat these once the drug reaches steady state and annually thereafter (see “Steps to Minimize Risk of TdP” table).

If the baseline or follow-up ECG shows a QTc interval of 470–500 ms (for males) or 480–500 ms (for females), we consider substituting the medication with an alternative, non-QT-prolonging agent, or else we try to reduce the medication dose when possible. We weigh the risks and benefits before making any medication changes—many patients with borderline QTc intervals can safely continue their medications. Just be vigilant for any potentially worrisome symptoms like syncope or shortness of breath.

Another cause for worry is a sudden increase of 60 ms or more in the QTc interval. In these cases, we follow the steps mentioned above—in other words, we try to substitute the medication with a non-QT-prolonging agent, reduce the dose when possible, and correct any electrolyte imbalances.

When should we obtain a cardiology consultation?

If a follow-up ECG reveals a QTc interval of 500 ms or more, we immediately discontinue the medication and obtain a cardiology consultation. Cardiologists are likely to recommend continuous ECG telemetry or repeat ECGs every two to four hours until normalized (Trinkley et al, 2013).

It’s wise to obtain cardiology consultations for patients with heart disease, with multiple QT-prolonging risk factors, on particularly high-risk medications (eg, IV haloperidol), who experience sudden increases in QTc, and/or whose QTc interval reaches or exceeds 500 ms. We also recommend cardiology consults when patients on QT-prolonging agents report new-onset syncope, dizziness, or palpitations.

It’s helpful to consult pediatric cardiologists when prescribing QT-prolonging medications to children as little is known about the effects of these medications in this population (Funk MC et al, Am J Psychiatry 2020;177(3):273–274). Adding to the complexity, QT values vary at different stages of childhood and adolescence.

Special populations

Electrolyte imbalances associated with eating disorders (especially anorexia nervosa and bulimia) and malnutrition (eg, following prolonged use of substances like alcohol and methamphetamines) increase the risk of QT prolongation. These patients should be monitored closely with repeat ECGs and electrolyte panels at least yearly, and with any new-onset symptoms such as dizziness or syncope.

Contrary to what many might believe, patients with implanted pacemakers and cardioverters/defibrillators are not protected against QT prolongation and TdP. Pacemaker settings do not allow for capture of TdP, and QT-prolonging medications may interfere with cardioversion. This can result in life-threatening, recurrent ventricular arrhythmias, known as an electrical or ICD storm (ICD stands for “implantable cardioverter defibrillator”). These patients are at greater risk, not less (Funk et al, 2020).

QT prolongation and TdP risks associated with specific psychiatric medications

Nearly every category of psychiatric medication includes low-risk and high-risk options. Here we will summarize data for specific medications, much of it drawn from the APA Resource Document on QTc Prolongation and Psychotropic Medications (Funk et al, 2020; see “Risk of QT Prolongation With Psychiatric Medications” table for a quick reference).

Antidepressants

While all SSRIs/SNRIs can increase the QT interval, they are generally considered safe. Sertraline is the best-studied SSRI and appears safe even in patients with QT-prolonging risk factors. Citalopram, which carries an FDA warning of QT prolongation above 40 mg daily, has minimal effects on the QTc interval in healthy patients, even when the dose is escalated to 60 mg. However, for patients with risk factors such as age >60 years, the QT prolongation can become clinically significant above 20 mg daily. Escitalopram’s QT prolongation is not clinically significant, and it does not carry an FDA warning (Trinkley et al, 2013).

Tricyclic antidepressants, particularly amitriptyline and maprotiline, produce risky QT prolongation in cardiac patients and in overdose. Venlafaxine on rare occasions can prolong the QT interval, particularly in elderly patients. Since data on mirtazapine are contradictory, the FDA advises that it should be used cautiously in patients at risk for QT prolongation. Bupropion appears to have little effect on the QTc interval at therapeutic doses and is a reasonable option for patients at risk for ventricular arrhythmias. Desvenlafaxine and duloxetine similarly appear to have little effect on the QTc interval. Data on newer antidepressants (levomilnacipran, vilazodone, vortioxetine) are too sparse to draw conclusions on QT prolongation risks.

Antipsychotics

All antipsychotics increase the QTc, but low-potency first-generation drugs, particularly thioridazine, appear most prone. IV haloperidol has been associated with TdP, and the FDA recommends cardiac monitoring during administration. Ziprasidone produces the most clinically significant QT prolongation among the second-generation agents. There is an FDA warning for quetiapine, though QT prolongation is modest even at 750 mg daily. Asenapine, brexpiprazole, clozapine, lurasidone, olanzapine, paliperidone, and risperidone do not appear to cause clinically significant QT prolongation, and aripiprazole’s effects on the QT interval are minimal.

Mood stabilizers

Lithium can impact the QTc significantly when levels exceed 1.2 mEq/L or in the context of hypokalemia. Carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and valproate do not cause QT prolongation.

Anxiolytics

Benzodiazepines and buspirone have little effect on the QTc interval.

Stimulants

Amphetamines and methylphenidates do not produce clinically significant effects on the QTc interval in most cases. However, be cautious when using these agents for patients with suspected heart disease.

Others

Buprenorphine confers less risk than methadone and should be used for patients with QTc >450 ms. Methadone should not be initiated until risk factors for QT prolongation are evaluated and addressed (eg, hypokalemia), and ECGs should be obtained at baseline and periodically, especially for daily doses above 120 mg (Martin JA et al, J Addict Dis 2011;30(4):283–306). Be cautious when using diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine as they are often co-prescribed with other QT-prolonging medications—the use of two or more QT-prolonging medications greatly increases the risk of QT interval prolongation.

Carlat Verdict

Most patients can safely take psychiatric medications with little worry about QTc prolongation. Whenever possible, avoid the combined use of QTc-prolonging medications and be careful with certain patients, especially those with heart disease, age over 65 years, and electrolyte imbalances. Monitor ECG and electrolytes regularly after prescribing thioridazine, ziprasidone, IV haloperidol, methadone; citalopram > 40 mg (over 20 mg for patients over age 60 years); and for any patients with new onset syncope, palpitations, or dizziness.

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)