Psychiatric Medication–Induced Hyperprolactinemia

Niki Karavitaki, MD. Senior Clinical Lecturer, Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research, University of Birmingham. Honorary Consultant Endocrinologist, Queen Elizabeth Hospital. Birmingham, UK.

Athanasios Fountas, MD. Clinical Research Fellow, Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham. Birmingham, UK.

Dr. Karavitaki has disclosed that she has given webinars for Pfizer on the topic of acromegaly in February 2021 and January 2022. Dr. Hendrick has reviewed the content of this interview and determined that there is no commercial bias as a result of these financial relationships. Dr. Fountas has disclosed no relevant financial or other interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

A 26-year-old female patient with schizophrenia tells you she is certain she is pregnant. You run a pregnancy test, which comes back negative, but she continues to insist that she is pregnant “because I haven’t had a period in three months.” She began risperidone 2 mg twice daily about four months earlier. You check her prolactin level, and it is 105 ng/mL.

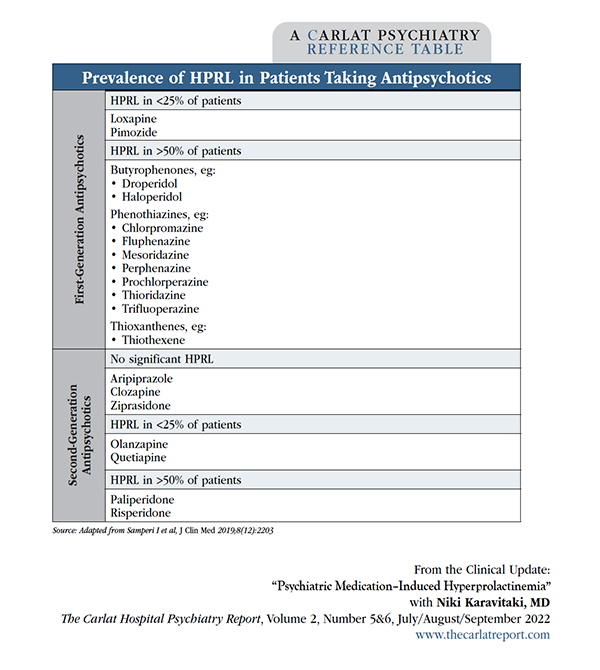

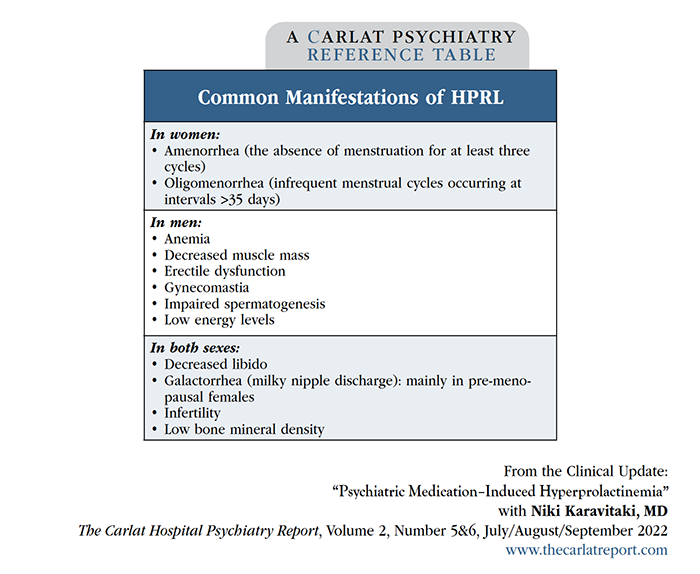

Most patients on antipsychotic medications have prolactin levels that are significantly higher than normal (>25 ng/mL for nonpregnant women and >16 ng/mL for men). You have most likely heard about missed menstrual cycles or galactorrhea (milky nipple discharge) from your female patients, while your male patients have probably complained of gynecomastia (enlarged breasts), impotence, and low sexual desire after taking antipsychotic medications. These are common manifestations of hyperprolactinemia (HPRL; see table for more). Certain antipsychotics are more likely to raise prolactin levels, especially paliperidone, risperidone, and many of the first-generation agents.

Table: Prevalence of HPRL in Patients Taking Antipsychotics

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Why do so many antipsychotics raise prolactin levels? Normally, dopamine inhibits prolactin synthesis and secretion. Since antipsychotics block dopamine receptors, the brakes that dopamine puts on prolactin are removed, leading to higher prolactin levels. First-generation antipsychotics produce more severe HPRL (two to three times the upper limit of reference range). In contrast, second-generation antipsychotics usually produce a milder prolactin increase due to their lower affinity for the D2 receptor, with the exceptions of paliperidone and risperidone (which, especially at higher doses, increase prolactin similarly to first-generation antipsychotics).

You might be surprised to know that several antidepressants also cause HPRL, particularly clomipramine, mainly via serotonergic pathways. This effect is mostly mild and rarely symptomatic, although occasionally female patients will report galactorrhea or missed menstrual cycles; clomipramine appears to be the most likely to cause this side effect (Coker F and Taylor D, CNS Drugs 2010;24(7):563–574).

Table: “Common Manifestations of HPRL”

(Click to view full-size PDF.)

Should we worry about HPRL?

It’s easy to overlook HPRL because its symptoms are not readily apparent and patients are often embarrassed to tell us about them. However, prolactin-related side effects, if unaddressed, significantly increase medication nonadherence. HPRL causes hypogonadism by suppressing gonadotropin-releasing hormone, resulting in menstrual irregularities, infertility, and decreased libido in women. Men experience erectile dysfunction, reduced libido, impaired spermatogenesis, gynecomastia, anemia, decreased muscle mass, and low energy levels. Galactorrhea is a common manifestation of HPRL in pre-menopausal women; it is less frequent in post-menopausal women and rarely occurs in men.

Loss of bone density is one of the most significant long-term consequences of sustained HPRL. Many studies have reported significantly higher rates of osteoporosis and bone fractures in patients taking antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia (Stubbs B et al, Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2015;37(2):126–133).

Diagnostic approach

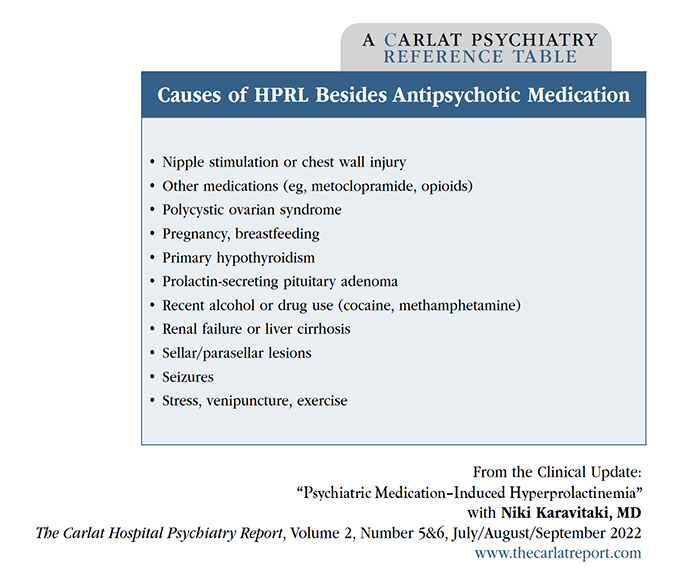

We recommend getting a baseline prolactin level before patients begin a psychiatric medication that is likely to cause HPRL. Check this level again in three months—sooner if you see symptoms of hyperprolactinemia. A prolactin level can be drawn at any time of day, but a few things can artificially cause a transient rise in prolactin, including exercise, nipple stimulation, and even the stress of getting stuck by a needle.

What do you do if your patient’s prolactin level is elevated? A first step is to rule out an elevated level of macroprolactin, which is a physiologically inactive form of prolactin. While few clinicians have heard about this, studies show that macroprolactin causes a false HPRL diagnosis in about 19% of cases (Che Soh NAA et al, Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(21):8199). Unfortunately, not all labs offer this test. Assuming that no macroprolactin is present, your next step is to exclude other causes of increased prolactin, such as pregnancy, hypothyroidism, and kidney or liver dysfunction. A rare cause of high prolactin is a pituitary tumor, which typically presents with headaches and vision changes. If you stop the patient’s antipsychotic and the HPRL persists, consider consulting an endocrinologist, who will likely order an MRI or CT scan to rule out a pituitary tumor.

Table: Causes of HPRL Besides Antipsychotic Medication

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

Management strategies

If your patient has asymptomatic HPRL, you don’t need to do anything. Continue the antipsychotic and check prolactin annually.

For patients who have symptoms, switch to a different agent with “prolactin-sparing” potential, such as aripiprazole, clozapine, or ziprasidone. Another option is to decrease the dose, as psychiatric medication–induced HPRL is usually dose related—but patients’ psychiatric symptoms might not respond well to lower antipsychotic doses. A nice psychopharm trick to have up your sleeve is adding low-dose aripiprazole (5–15 mg/day) as an adjunctive therapy. Aripiprazole reduces prolactin levels due to its partial agonistic activity at D2 receptors. Several studies have found this strategy effective (Zheng W et al, Gen Psychiatry 2019;32(5):e100091). If you’ve tried all the above and the HPRL continues, you can try prescribing a dopamine agonist such as cabergoline or bromocriptine. Be mindful that doing so will mean you are working at odds with the dopamine-blocking properties of the antipsychotic, and the patient’s psychiatric symptoms could worsen. For female patients, another option is to add a birth control pill, which will replenish estrogen that has been lowered by the prolactin. A more direct approach is using hormone replacement therapy—though this would usually be prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician or OB-GYN.

Table: HPRL Management Strategies

(Click to view full-sized PDF.)

You switch your patient to aripiprazole 15 mg twice daily. Two weeks later, you recheck her prolactin level and find it has dropped to 22 ng/mL. A few days later, your patient informs you that her menstrual cycles have resumed.

CHPR VERDICT: Don’t ignore HPRL—switch meds, add aripiprazole, add a dopamine agonist, or encourage hormone replacement therapy. Your patients will be happy you went the extra mile!

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)