Home » Abilify MyCite: Patient Care Breakthrough or Patent Extender?

Abilify MyCite: Patient Care Breakthrough or Patent Extender?

March 1, 2018

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

You’ve probably heard about a new “digital pill” called Abilify MyCite. The product, which was FDA approved in November 2017, is the first drug in the U.S. with a digital ingestion tracking system.

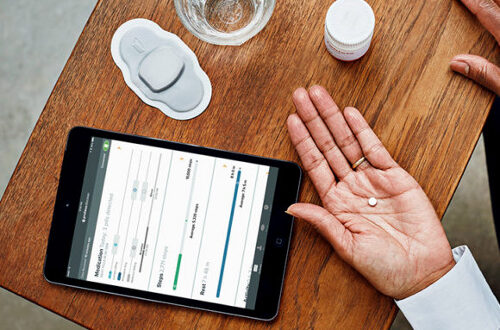

MyCite consists of an aripiprazole pill that contains an embedded tiny sensing device (about the size of a grain of sand) called the ingestible event marker (IEM). Patients swallow the pill like any other, and once it dissolves, the IEM comes in contact with gastric fluids—which triggers the device to emit a signal. This signal communicates with a wearable sensor contained in a small patch on the patient’s abdomen. The patch then transmits a signal to a mobile application, allowing the patient to view compliance data on a smartphone. Patients can share these data with whomever they want—such as a physician or a family member. If your patients give you signed consent, you can access their ingestion data via a web-based portal or app.

The idea behind MyCite is that it will allow you to tell whether your patients are compliant with their medication. However, Otsuka, the manufacturer, has not presented any data showing that this formulation improves compliance, and the FDA indication explicitly states that “the ability of Abilify MyCite to improve patient compliance or modify aripiprazole dosage has not been established.” The label also points out that the system is not foolproof, and that ingestion is not always detected.

Nonetheless, it’s likely that this innovation will help you track your patients’ compliance. This would be helpful for those patients who are either forgetful or ambivalent about taking their antipsychotic. Currently, our standard approach for such patients is to simply ask them if they are taking their meds, but patients are often inclined to please us and will usually say “yes” even if they have skipped doses. If they are doing poorly, we think about increasing doses or making a medication change. It would be nice if we could definitively verify whether the drug is actually getting into the patient’s system before we opt for any change to medication.

Conversely, some patients admit that they don’t take their meds because, for example, they don’t think they need them or they are worried about side effects. Such patients will presumably toss MyCite into the trash just as they would regular aripiprazole. For these patients, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic might be more appropriate—assuming they consent.

As we wait for empirical data to guide us in our use of MyCite, here are some of the major potential benefits and drawbacks of the formulation.

Potential benefits

Potential drawbacks

Specific rollout dates for Abilify MyCite have yet to be announced, but Otsuka says it will be available sometime in 2018. Initially, the company plans to conduct beta testing by rolling it out to a select number of health plans and providers “who identify a limited number of appropriate adults with schizophrenia, bipolar I disorder, or major depressive disorder.” The company’s goal with this small initial rollout is to ensure that the technology works and is bug free.

TCPR Verdict: Abilify MyCite sounds creepier than it is. Depending on insurance coverage, it’s worth trying for patients who are ambivalent about taking their meds.

General PsychiatryMyCite consists of an aripiprazole pill that contains an embedded tiny sensing device (about the size of a grain of sand) called the ingestible event marker (IEM). Patients swallow the pill like any other, and once it dissolves, the IEM comes in contact with gastric fluids—which triggers the device to emit a signal. This signal communicates with a wearable sensor contained in a small patch on the patient’s abdomen. The patch then transmits a signal to a mobile application, allowing the patient to view compliance data on a smartphone. Patients can share these data with whomever they want—such as a physician or a family member. If your patients give you signed consent, you can access their ingestion data via a web-based portal or app.

The idea behind MyCite is that it will allow you to tell whether your patients are compliant with their medication. However, Otsuka, the manufacturer, has not presented any data showing that this formulation improves compliance, and the FDA indication explicitly states that “the ability of Abilify MyCite to improve patient compliance or modify aripiprazole dosage has not been established.” The label also points out that the system is not foolproof, and that ingestion is not always detected.

Nonetheless, it’s likely that this innovation will help you track your patients’ compliance. This would be helpful for those patients who are either forgetful or ambivalent about taking their antipsychotic. Currently, our standard approach for such patients is to simply ask them if they are taking their meds, but patients are often inclined to please us and will usually say “yes” even if they have skipped doses. If they are doing poorly, we think about increasing doses or making a medication change. It would be nice if we could definitively verify whether the drug is actually getting into the patient’s system before we opt for any change to medication.

Conversely, some patients admit that they don’t take their meds because, for example, they don’t think they need them or they are worried about side effects. Such patients will presumably toss MyCite into the trash just as they would regular aripiprazole. For these patients, a long-acting injectable antipsychotic might be more appropriate—assuming they consent.

As we wait for empirical data to guide us in our use of MyCite, here are some of the major potential benefits and drawbacks of the formulation.

Potential benefits

- It may help determine compliance, and therefore help us decide whether a poor response is due to the wrong medication or to skipped doses.

- It may decrease conflicts between patients and family members. Family members are often concerned that patients are not taking their medications, leading to conflict and nagging. Family conflict can sometimes cause patients to decompensate, leading to rehospitalizations.

Potential drawbacks

- Some have wondered if putting a computer chip in a pill will make schizophrenic patients more paranoid. But a 2013 study of 27 patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder found that such patients tolerated ingestible sensors well. None of the participants became paranoid about the technology, 19 of them found the digital pill concept easy to understand, and 24 said they believed the technology could be useful for them (Kane JM et al, J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74(6):533–540).

- There are some concerns about privacy of the compliance data. To address this, the system requires patients to give informed consent before releasing their data. In addition, each time patients ingest a pill, they can decide whether to continue sharing the data. If they decide to opt out, they can simply turn off the app at any time.

- Although there is no information on cost yet, MyCite will presumably be much more expensive than a regular aripiprazole prescription. It’s unclear how many health insurers will cover it.

- Is ingesting computer chips safe? According to the manufacturer, ingesting the tiny chips didn’t cause any adverse effects. The receiving patch can cause some minor skin irritation.

Specific rollout dates for Abilify MyCite have yet to be announced, but Otsuka says it will be available sometime in 2018. Initially, the company plans to conduct beta testing by rolling it out to a select number of health plans and providers “who identify a limited number of appropriate adults with schizophrenia, bipolar I disorder, or major depressive disorder.” The company’s goal with this small initial rollout is to ensure that the technology works and is bug free.

TCPR Verdict: Abilify MyCite sounds creepier than it is. Depending on insurance coverage, it’s worth trying for patients who are ambivalent about taking their meds.

Issue Date: March 1, 2018

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)