Home » Latuda: An Evaluation of Its Usefulness

Latuda: An Evaluation of Its Usefulness

February 1, 2015

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Daniel Carlat, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Publisher, The Carlat Report.

Dr. Carlat has disclosed that he has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial company pertaining to this educational activity.

With nine other atypical antipsychotics already on the market (some of which are available as generics), did we really need another one?

Given the pesky side effects of antipsychotics, maybe we did. Let’s take a look at what we know so far about Latuda (lurasidone) in an effort to figure out how to incorporate it into our clinical toolbox.

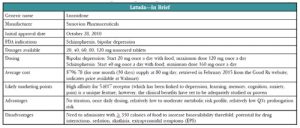

Latuda was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in schizophrenia in late 2010. The pharmaceutical company’s marketing team kicked into high gear early on, and recruited psychiatrists to attend “speaker training” junkets in Miami (they even invited Dr. Carlat—see http://bit.ly/14EJiw0 for his commentary). Nonetheless, Latuda had a somewhat sluggish start as it launched on the heels of Saphris (asenapine) and Fanapt (iloperidone)

Why We Are Hearing More About Latuda Lately

It took a while to work out the right dosing and more dosages were made available in 2011 and 2012 (see below for more on this). In June of 2013, we began hearing more about Latuda when it received FDA approval for an indication for bipolar depression, and our patients did, too—TV ads were rolled out early in 2014. At this point, sales of Latuda are up, with US sales of $202 million in the company’s fiscal year 2012 and $421 million in fiscal year 2013 (http://bit.ly/15bnloI). In 2014, Latuda broke into the list of the top 100 best-selling drugs in any specialty (http://bit.ly/1CryFbD) and its manufacturer, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, forecast projected sales of $610 million for 2014 in its annual report. Sunovion continues to seek new markets and is on track for FDA submissions, as monotherapy, for both bipolar maintenance and major depression.

How It Works and What the Studies Show

Like the other atypical antipsychotics, Latuda is both a serotonin (5-HT2A) and dopamine (D2) antagonist. In addition, Latuda blocks 5-HT7 receptors and is a partial agonist at 5-H21A receptors. Partial agonism at 5-HT1A receptors may be associated with some antidepressant effects (think BuSpar, Viibryd, Geodon, or Abilify which have shown a varying range of antidepressant effects). We don’t know as much about what blockade of 5-HT7 receptors may contribute clinically. Some animal studies have suggested reversal of lab-induced learning and memory impairments but whether this will translate into treating cognitive deficits in our patients remains to be seen (Ballaz SJ et al, Neuroscience 2007;149(1):192–202).

Schizophrenia. Latuda 40 mg to 120 mg/day was effective in four of five placebo-controlled schizophrenia studies (Sanford M, CNS Drugs 2013;27(1):67–80). Two of the studies included active control arms (Zyprexa 15 mg/day in one and Seroquel XR 600 mg/day in the other); however, neither study was powered adequately to directly compare the active drugs to Latuda. In these studies, Latuda 40 mg to 160 mg/day, Zyprexa, and Seroquel XR were all better than placebo at improving symptoms on the standard schizophrenia rating scales. A 12-month extension trial showed “noninferiority” to Seroquel XR (meaning that Latuda is not worse than the comparator by more than a small pre-specified amount) with numerically lower relapse probability of 24% for Latuda patients compared to 34% of Seroquel patients (Loebel A et al, Schizophr Res 2013;147(1):95–102). The one negative study used an active control arm (Haldol 10 mg/day), and neither Latuda nor Haldol patients, showed significant improvement compared to those receiving placebo (Sanford M, op.cit). Study design may have contributed to this outcome as it had a relatively small sample size and dropout rates were quite high (more than half of all subjects quit).

Bipolar depression. Latuda’s efficacy in bipolar depression was established in two six-week placebo-controlled studies (Citrome L, CNS Drugs 2013;27(11):879–911). The first study compared two dose ranges of Latuda—low dose (20 mg to 60 mg/day) and a high dose (80 mg to 120 mg/day) vs. placebo. Interestingly, there was no difference in efficacy between the two doses in terms of either response rate (53% vs. 51%, respectively) or remission rate (42% and 40%). Both doses bested placebo (30% response, 25% remission). So, while Latuda as monotherapy was found to be more effective than placebo in bipolar depression, the higher dose did not seem to offer additional benefit compared to the lower dose. In the second study, Latuda 20 mg to 120 mg/day as adjunctive therapy (with lithium or valproate) for bipolar depression resulted in response rates of 57% for Latuda compared to 42% for placebo, while remission rates were 50% for Latuda vs. 35% for placebo. Latuda’s efficacy in bipolar depression has not been compared to other medications, only placebo. Efficacy in bipolar mania and maintenance remain to be seen.

Side Effects

The most common side effects reported in clinical trials of Latuda vs. placebo are akathisia (13% vs. 3%), other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) (14 % vs. 6%), nausea (10% vs. 5%), somnolence (17% vs. 7%), and insomnia (10% vs. 8%). Sedation and akathisia are dose-related, ranging from 6% at 20 mg/day to 22% at 120 mg/day.

A 12-month safety and tolerability study compared Latuda 40 mg to 120 mg/day, and risperidone 2 mg to 6 mg/day in stable outpatients with schizophrenia (Citrome L et al, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27(3):165–176). Latuda caused significantly more akathisia than risperidone (14.3% vs. 7.9%) and numerically less dystonia (3.1% vs. 5.9%) and Parkinsonism (4.3% vs. 5.4%). Importantly, Latuda was half as likely as risperidone to cause significant weight gain (≥7% of body weight) (7% vs. 14%). There have been rare reports of orthostatic hypotension and syncope that may be related to its alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonism. Latuda appears to have a low risk of QT interval prolongation and a favorable metabolic profile with minimal increases in lipids, glucose, or prolactin compared to placebo (4% to 14% vs. 5% to 10%). The increases in prolactin were minimal (2 ng/ml to 7ng/ml), dose-related, and likely not clinically significant.

Dosing Issues

One of the peculiarities of dosing Latuda is that taking it with food increases serum levels of the drug by a significant amount. Taking Latuda with a minimum of 350 calories (by the way, this is not a small snack—it could be two eggs, turkey bacon, and buttered wheat toast; chicken sandwich and yogurt; soup, crackers and fruit; fish, mashed potatoes, and peas; chicken, brown rice, and vegetables) has an effect of doubling or even tripling serum levels. Keep this in mind when reading these dosing recommendations and remember that in all studies, Latuda was given within 30 minutes of eating. So, expect less robust results if your patients aren’t reliable about eating when taking their medication.

When Latuda first launched in 2010 for schizophrenia, it was available only in the 40 mg and 80 mg dosages. You started your patients on 40 mg and then went up to 80 mg if you didn’t get adequate response. This recommendation was based on the earliest studies, which showed adequate efficacy at these doses with fewer side effects than the higher doses. Pooled analyses later showed better response rates at the 120 mg and 160 mg daily doses (response rates went from 58% to 64% at the lower doses to 79% at 160 mg/day, comparable to the response rates for Zyprexa and Seroquel in those studies) so the company went back to the FDA and had the dosing range amended (Citrome L, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 2012;6(2):76–85).

The dosing recommendation for patients with schizophrenia now is to start with 40 mg once a day with food (within 30 minutes of eating) and increase per response to a maximum of 160 mg once a day. The expansion of the dosing range was probably a good thing because in addition to the trial data suggesting better efficacy, we can probably guess that many “real world” patients may not reliably take their dose with the recommended caloric intake, thereby inadvertently lowering the amount ultimately delivered.

In the bipolar depression studies, the higher doses (80 mg to 120 mg/day) didn’t appear to provide any additional efficacy compared to the lower range of 20 mg to 60 mg/day so the recommendation is to start with 20 mg once a day with food and increase per response to a target range of 20 mg to 80 mg/day, with a maximum of 120 mg/day, if needed.

Dosing need not be adjusted in the elderly, but patients with moderate to severe renal or hepatic impairment should get no more than 50% of the usual dose. And, since Latuda relies heavily on CYP3A4 for metabolism, be aware of potentially significant drug interactions. Potent inhibitors (some antifungals such as ketoconazole and voriconazole, some antibiotics such as clarithromycin, antivirals such as ritonavir and boceprevir, nefazodone, and grapefruit juice) can increase Latuda levels by as much as seven-fold and should be avoided. Moderate inhibitors such as diltiazem, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin may increase Latuda levels two-fold, so the Latuda dose should be halved. Strong 3A4 inducers such as rifampin, carbamazepine, St. John’s wort, and phenytoin may decrease Latuda by seven-fold and should also be avoided (Chiu YY et al, Drug Metabol Drug Interact 2014;29(3):191–202).

Putting It All Together

When the second generation antipsychotics first appeared on the scene, we were hopeful these agents would have broader efficacy, including improvements in cognition. There has been little evidence to support this, so it’s hard to believe the hype about cognition and Latuda. Thus far, one preliminary 21-day study comparing Latuda and Geodon (no placebo arm) showed no difference in cognitive functioning (Harvey PD et al, Schizophr Res 2011;127(1–3):188–94).

Latuda’s place in therapy may well be as a “me too” atypical antipsychotic in terms of efficacy in psychosis, although it does have an advantage over some of its competitors in terms of metabolic side effects. It’s not a completely clean drug, since it can cause significant akathisia and sedation. You might think of it as being a bit like Abilify (akathisia, minimal weight gain), with a little Seroquel sprinkled in (sedation). It may be a bit more than just a “me too” in terms of other uses such as bipolar depression for which other options (Seroquel, Symbyax) cause more significant weight gain.

In Summary

TCPR's Verdict

The promising efficacy data in bipolar depression, once daily dosing, and favorable QT, weight, and metabolic profile make this an appealing choice. However, the need to administer with food, the significant akathisia and other EPS, and the potential for drug interactions will limit its use somewhat.

General PsychiatryGiven the pesky side effects of antipsychotics, maybe we did. Let’s take a look at what we know so far about Latuda (lurasidone) in an effort to figure out how to incorporate it into our clinical toolbox.

Latuda was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in schizophrenia in late 2010. The pharmaceutical company’s marketing team kicked into high gear early on, and recruited psychiatrists to attend “speaker training” junkets in Miami (they even invited Dr. Carlat—see http://bit.ly/14EJiw0 for his commentary). Nonetheless, Latuda had a somewhat sluggish start as it launched on the heels of Saphris (asenapine) and Fanapt (iloperidone)

Why We Are Hearing More About Latuda Lately

It took a while to work out the right dosing and more dosages were made available in 2011 and 2012 (see below for more on this). In June of 2013, we began hearing more about Latuda when it received FDA approval for an indication for bipolar depression, and our patients did, too—TV ads were rolled out early in 2014. At this point, sales of Latuda are up, with US sales of $202 million in the company’s fiscal year 2012 and $421 million in fiscal year 2013 (http://bit.ly/15bnloI). In 2014, Latuda broke into the list of the top 100 best-selling drugs in any specialty (http://bit.ly/1CryFbD) and its manufacturer, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, forecast projected sales of $610 million for 2014 in its annual report. Sunovion continues to seek new markets and is on track for FDA submissions, as monotherapy, for both bipolar maintenance and major depression.

How It Works and What the Studies Show

Like the other atypical antipsychotics, Latuda is both a serotonin (5-HT2A) and dopamine (D2) antagonist. In addition, Latuda blocks 5-HT7 receptors and is a partial agonist at 5-H21A receptors. Partial agonism at 5-HT1A receptors may be associated with some antidepressant effects (think BuSpar, Viibryd, Geodon, or Abilify which have shown a varying range of antidepressant effects). We don’t know as much about what blockade of 5-HT7 receptors may contribute clinically. Some animal studies have suggested reversal of lab-induced learning and memory impairments but whether this will translate into treating cognitive deficits in our patients remains to be seen (Ballaz SJ et al, Neuroscience 2007;149(1):192–202).

Schizophrenia. Latuda 40 mg to 120 mg/day was effective in four of five placebo-controlled schizophrenia studies (Sanford M, CNS Drugs 2013;27(1):67–80). Two of the studies included active control arms (Zyprexa 15 mg/day in one and Seroquel XR 600 mg/day in the other); however, neither study was powered adequately to directly compare the active drugs to Latuda. In these studies, Latuda 40 mg to 160 mg/day, Zyprexa, and Seroquel XR were all better than placebo at improving symptoms on the standard schizophrenia rating scales. A 12-month extension trial showed “noninferiority” to Seroquel XR (meaning that Latuda is not worse than the comparator by more than a small pre-specified amount) with numerically lower relapse probability of 24% for Latuda patients compared to 34% of Seroquel patients (Loebel A et al, Schizophr Res 2013;147(1):95–102). The one negative study used an active control arm (Haldol 10 mg/day), and neither Latuda nor Haldol patients, showed significant improvement compared to those receiving placebo (Sanford M, op.cit). Study design may have contributed to this outcome as it had a relatively small sample size and dropout rates were quite high (more than half of all subjects quit).

Bipolar depression. Latuda’s efficacy in bipolar depression was established in two six-week placebo-controlled studies (Citrome L, CNS Drugs 2013;27(11):879–911). The first study compared two dose ranges of Latuda—low dose (20 mg to 60 mg/day) and a high dose (80 mg to 120 mg/day) vs. placebo. Interestingly, there was no difference in efficacy between the two doses in terms of either response rate (53% vs. 51%, respectively) or remission rate (42% and 40%). Both doses bested placebo (30% response, 25% remission). So, while Latuda as monotherapy was found to be more effective than placebo in bipolar depression, the higher dose did not seem to offer additional benefit compared to the lower dose. In the second study, Latuda 20 mg to 120 mg/day as adjunctive therapy (with lithium or valproate) for bipolar depression resulted in response rates of 57% for Latuda compared to 42% for placebo, while remission rates were 50% for Latuda vs. 35% for placebo. Latuda’s efficacy in bipolar depression has not been compared to other medications, only placebo. Efficacy in bipolar mania and maintenance remain to be seen.

Side Effects

The most common side effects reported in clinical trials of Latuda vs. placebo are akathisia (13% vs. 3%), other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) (14 % vs. 6%), nausea (10% vs. 5%), somnolence (17% vs. 7%), and insomnia (10% vs. 8%). Sedation and akathisia are dose-related, ranging from 6% at 20 mg/day to 22% at 120 mg/day.

A 12-month safety and tolerability study compared Latuda 40 mg to 120 mg/day, and risperidone 2 mg to 6 mg/day in stable outpatients with schizophrenia (Citrome L et al, Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27(3):165–176). Latuda caused significantly more akathisia than risperidone (14.3% vs. 7.9%) and numerically less dystonia (3.1% vs. 5.9%) and Parkinsonism (4.3% vs. 5.4%). Importantly, Latuda was half as likely as risperidone to cause significant weight gain (≥7% of body weight) (7% vs. 14%). There have been rare reports of orthostatic hypotension and syncope that may be related to its alpha-1 adrenergic receptor antagonism. Latuda appears to have a low risk of QT interval prolongation and a favorable metabolic profile with minimal increases in lipids, glucose, or prolactin compared to placebo (4% to 14% vs. 5% to 10%). The increases in prolactin were minimal (2 ng/ml to 7ng/ml), dose-related, and likely not clinically significant.

Dosing Issues

One of the peculiarities of dosing Latuda is that taking it with food increases serum levels of the drug by a significant amount. Taking Latuda with a minimum of 350 calories (by the way, this is not a small snack—it could be two eggs, turkey bacon, and buttered wheat toast; chicken sandwich and yogurt; soup, crackers and fruit; fish, mashed potatoes, and peas; chicken, brown rice, and vegetables) has an effect of doubling or even tripling serum levels. Keep this in mind when reading these dosing recommendations and remember that in all studies, Latuda was given within 30 minutes of eating. So, expect less robust results if your patients aren’t reliable about eating when taking their medication.

When Latuda first launched in 2010 for schizophrenia, it was available only in the 40 mg and 80 mg dosages. You started your patients on 40 mg and then went up to 80 mg if you didn’t get adequate response. This recommendation was based on the earliest studies, which showed adequate efficacy at these doses with fewer side effects than the higher doses. Pooled analyses later showed better response rates at the 120 mg and 160 mg daily doses (response rates went from 58% to 64% at the lower doses to 79% at 160 mg/day, comparable to the response rates for Zyprexa and Seroquel in those studies) so the company went back to the FDA and had the dosing range amended (Citrome L, Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 2012;6(2):76–85).

The dosing recommendation for patients with schizophrenia now is to start with 40 mg once a day with food (within 30 minutes of eating) and increase per response to a maximum of 160 mg once a day. The expansion of the dosing range was probably a good thing because in addition to the trial data suggesting better efficacy, we can probably guess that many “real world” patients may not reliably take their dose with the recommended caloric intake, thereby inadvertently lowering the amount ultimately delivered.

In the bipolar depression studies, the higher doses (80 mg to 120 mg/day) didn’t appear to provide any additional efficacy compared to the lower range of 20 mg to 60 mg/day so the recommendation is to start with 20 mg once a day with food and increase per response to a target range of 20 mg to 80 mg/day, with a maximum of 120 mg/day, if needed.

Dosing need not be adjusted in the elderly, but patients with moderate to severe renal or hepatic impairment should get no more than 50% of the usual dose. And, since Latuda relies heavily on CYP3A4 for metabolism, be aware of potentially significant drug interactions. Potent inhibitors (some antifungals such as ketoconazole and voriconazole, some antibiotics such as clarithromycin, antivirals such as ritonavir and boceprevir, nefazodone, and grapefruit juice) can increase Latuda levels by as much as seven-fold and should be avoided. Moderate inhibitors such as diltiazem, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin may increase Latuda levels two-fold, so the Latuda dose should be halved. Strong 3A4 inducers such as rifampin, carbamazepine, St. John’s wort, and phenytoin may decrease Latuda by seven-fold and should also be avoided (Chiu YY et al, Drug Metabol Drug Interact 2014;29(3):191–202).

Putting It All Together

When the second generation antipsychotics first appeared on the scene, we were hopeful these agents would have broader efficacy, including improvements in cognition. There has been little evidence to support this, so it’s hard to believe the hype about cognition and Latuda. Thus far, one preliminary 21-day study comparing Latuda and Geodon (no placebo arm) showed no difference in cognitive functioning (Harvey PD et al, Schizophr Res 2011;127(1–3):188–94).

Latuda’s place in therapy may well be as a “me too” atypical antipsychotic in terms of efficacy in psychosis, although it does have an advantage over some of its competitors in terms of metabolic side effects. It’s not a completely clean drug, since it can cause significant akathisia and sedation. You might think of it as being a bit like Abilify (akathisia, minimal weight gain), with a little Seroquel sprinkled in (sedation). It may be a bit more than just a “me too” in terms of other uses such as bipolar depression for which other options (Seroquel, Symbyax) cause more significant weight gain.

In Summary

- Latuda was first approved by the FDA in 2010 for use in schizophrenia and later approved in 2013 for bipolar depression

- The newest of the atypicals, it’s on the list of the 100 top-selling drugs with projected sales of $610 million in 2014

- The need to administer it with food, a minimum of 350 calories, is a disadvantage

TCPR's Verdict

The promising efficacy data in bipolar depression, once daily dosing, and favorable QT, weight, and metabolic profile make this an appealing choice. However, the need to administer with food, the significant akathisia and other EPS, and the potential for drug interactions will limit its use somewhat.

KEYWORDS antipsychotics

Issue Date: February 1, 2015

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.webp?t=1729528747)