Home » Dialectical Behavior Therapy: A Primer

CLINICAL UPDATE

Dialectical Behavior Therapy: A Primer

March 1, 2012

From The Carlat Psychiatry Report

Josh Sonkiss, M.

Co-medical director, Behavioral Health Unit, Fairbanks Memorial Hospital

Dr. Sonkiss has disclosed that he has no relevant relationships or financial interests in any commercial companies pertaining to this educational activity.

A young woman with borderline personality disorder (BPD) calls your office for the third time in one week and reports she’s been cutting again. You are discharging a middle-aged alcoholic to residential treatment in another state, and you are afraid he might relapse on the plane. You are asked to consult on an orthopedic patient whose outrageous demands have the whole medical team in an uproar. In each of these situations, what should you do?

While there are many ways to manage scenarios like these, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) offers some particularly useful tools for psychiatrists and other clinicians. Marsha Linehan developed DBT to help patients with BPD (Linehan MM, Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: The Guilford Press;1993), and over the past two decades it has received strong empirical support. But DBT is by no means limited to treating borderline patients: a growing evidence base supports its use for treating substance-use disorders, eating disorders, depression, PTSD, and even impulsive violence in prison populations. Clinicians who are familiar with DBT have begun to realize they can successfully apply many of its techniques in everyday clinical practice.

So what is DBT? DBT combines principles of Zen mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, and supportive therapy. But DBT is not simply a hodgepodge of unrelated ideas. Mindfulness training is used specifically to help patients tolerate emotional distress without resorting to self-harm. Cognitive behavioral techniques are used to prevent catastrophizing thought distortions that can lead to the emotional turmoil often seen in BPD. And supportive therapy is used to keep patients engaged in treatment long enough to learn and apply the techniques. The term “dialectic,” with its aura of arcane, Hegelian philosophy, may confuse clinicians about its relevance—it is simply a method of resolving ambivalence through the synthesis of opposing positions. A classic example in DBT is that the patient must learn to accept herself exactly as she is, yet she must also change the behavior that makes her life intolerable.

Though seemingly abstract, DBT’s dialectic offers psychiatrists a practical tool they can use every time they meet with a “difficult” patient. Regardless of their behavior, DBT therapists always assume their patients are doing the best they can at any given moment. Sound like therapeutic nihilism? Far from it. DBT therapists also assume their patients can and will learn to do better, and by adopting these opposing viewpoints simultaneously, they help patients accept themselves in the moment while working hard to change. When I take a dialectical approach, I find it reduces my frustration with patients who might otherwise seem manipulative. It also helps patients overcome black-and-white thinking that can lead to feelings of guilt and hopelessness when they harm themselves, relapse into substance use, or fail to make desired improvements in behavior.

A Menu of DBT Skills

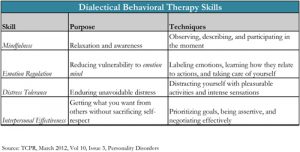

Much of DBT involves teaching patients new “skills” to replace maladaptive behavior. A psychiatrist familiar with DBT skills can select one or two to fit a patient’s needs and teach them on the fly. (For a complete explanation of DBT skills along with training exercises and worksheets, see Linehan MM, referenced previously.)

Mindfulness skills are the cornerstone of DBT and are based on Zen mindfulness. A key principle is that there are three basic mindsets in any situation: emotion mind, reasonable mind, and wise mind. Although emotion mind can lead to impulsive decisions and reasonable mind can fail when you need it most, both are considered valid. But true to its dialectical roots, DBT teaches that wise mind emerges from the synthesis of reason and emotion, and it is considered the most effective for solving problems and surviving crises.

Emotion regulation skills are easy to teach and very effective for patients whose intense, labile moods often lead them into trouble. For example, the acronym “PLEASE Master” reminds patients to take care of their physical health (by treating Physical iLlness, Eating, Avoiding drugs, Sleeping, and Exercising) and to do at least one thing each day to “Master” competence and self-respect. These precautions reduce the likelihood of self-harm, and in my experience they also work well for patients struggling with addiction and the triggers that can lead to relapse.

Distress tolerance skills are also known as crisis survival strategies. I most often recommend pleasurable distraction—which can be as simple as reading a book or watching a movie—in consultation-liaison settings where severe medical problems lead to pain, anxiety, and loss. With patients who cut or burn themselves, I often recommend squeezing ice cubes or snapping a rubber band against the skin as an equally painful but harmless alternative.

Interpersonal effectiveness skills are best taught when patients are not inpatients that have work or relationship problems once they get well enough to participate in their discharge plans. They’re also helpful for medical patients who are having trouble getting along with hospital staff.

Many borderline patients have learned that hurting themselves is the only way they can get help, and DBT is designed to reverse the unwitting reinforcement of “crisis behavior” that can occur in traditional modes of treatment. Through a process called contingency management, DBT therapists examine how patients somehow end up having their adaptive behaviors punished while their maladaptive behaviors get rewarded. Once you identify these dysfunctional patterns, you then use behavioral principles to create a new reinforcement schedule.

For example, instead of receiving an emergent appointment after an episode of cutting, a DBT patient who self-harms will typically be denied access to his or her therapist for 24 hours (someone else fills in, so the patient is never actually abandoned). On the other hand, adaptive behavior—such as applying DBT skills instead of self-harming—is rewarded by the therapist being available for telephone consultation outside of office hours.

In everyday practice, contingency management can be as effective as it is counter-intuitive. In outpatient settings, consider offering walk-in hours or more frequent appointments for borderline patients, ensuring they have access to care before their troubles reach a crisis stage. Try to resist the temptation to hospitalize after every instance of self-harm. On the other hand, in rare cases, some patients may benefit from brief, occasional admissions “whether they need it or not” when faced with ongoing personal crises. Fixed reinforcement schedules like this one translate readily to other inpatient and consultation-liaison settings, where demanding patients can disrupt entire wards. If patients are told the call button is only for emergencies, their behavior can escalate rapidly. But a short visit from a nurse or psych tech every 30 to 60 minutes—during which validation should be offered—is a better approach.

The technique of “validation” occupies a special place in the DBT toolbox. This is because patients who are constantly being pushed to change their self-defeating behaviors may experience this as being “invalidating.” Essentially, they feel that they are being criticized for being ill. To offer validation, I try to step beyond empathic reflection to let patients know their feelings make sense in the context of their own unique experience, even if I don’t agree their behavior is the best way to solve problems. For example, I might say, “I can see how in that situation, it seemed like overdosing was the only way you could get anyone to listen to you.” Validation is effective in a wide range of circumstances, including when borderline patients present in crisis, addicts struggle to maintain sobriety, or medical patients become angry at hospital staff. I even use it when I’m not at work!

DBT adapts well to a multitude of clinical situations. Although not all DBT techniques work for everyone, most psychiatrists and their patients will find something that works for them.

General Psychiatry Clinical UpdateWhile there are many ways to manage scenarios like these, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) offers some particularly useful tools for psychiatrists and other clinicians. Marsha Linehan developed DBT to help patients with BPD (Linehan MM, Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: The Guilford Press;1993), and over the past two decades it has received strong empirical support. But DBT is by no means limited to treating borderline patients: a growing evidence base supports its use for treating substance-use disorders, eating disorders, depression, PTSD, and even impulsive violence in prison populations. Clinicians who are familiar with DBT have begun to realize they can successfully apply many of its techniques in everyday clinical practice.

So what is DBT? DBT combines principles of Zen mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, and supportive therapy. But DBT is not simply a hodgepodge of unrelated ideas. Mindfulness training is used specifically to help patients tolerate emotional distress without resorting to self-harm. Cognitive behavioral techniques are used to prevent catastrophizing thought distortions that can lead to the emotional turmoil often seen in BPD. And supportive therapy is used to keep patients engaged in treatment long enough to learn and apply the techniques. The term “dialectic,” with its aura of arcane, Hegelian philosophy, may confuse clinicians about its relevance—it is simply a method of resolving ambivalence through the synthesis of opposing positions. A classic example in DBT is that the patient must learn to accept herself exactly as she is, yet she must also change the behavior that makes her life intolerable.

Though seemingly abstract, DBT’s dialectic offers psychiatrists a practical tool they can use every time they meet with a “difficult” patient. Regardless of their behavior, DBT therapists always assume their patients are doing the best they can at any given moment. Sound like therapeutic nihilism? Far from it. DBT therapists also assume their patients can and will learn to do better, and by adopting these opposing viewpoints simultaneously, they help patients accept themselves in the moment while working hard to change. When I take a dialectical approach, I find it reduces my frustration with patients who might otherwise seem manipulative. It also helps patients overcome black-and-white thinking that can lead to feelings of guilt and hopelessness when they harm themselves, relapse into substance use, or fail to make desired improvements in behavior.

A Menu of DBT Skills

Much of DBT involves teaching patients new “skills” to replace maladaptive behavior. A psychiatrist familiar with DBT skills can select one or two to fit a patient’s needs and teach them on the fly. (For a complete explanation of DBT skills along with training exercises and worksheets, see Linehan MM, referenced previously.)

Mindfulness skills are the cornerstone of DBT and are based on Zen mindfulness. A key principle is that there are three basic mindsets in any situation: emotion mind, reasonable mind, and wise mind. Although emotion mind can lead to impulsive decisions and reasonable mind can fail when you need it most, both are considered valid. But true to its dialectical roots, DBT teaches that wise mind emerges from the synthesis of reason and emotion, and it is considered the most effective for solving problems and surviving crises.

Emotion regulation skills are easy to teach and very effective for patients whose intense, labile moods often lead them into trouble. For example, the acronym “PLEASE Master” reminds patients to take care of their physical health (by treating Physical iLlness, Eating, Avoiding drugs, Sleeping, and Exercising) and to do at least one thing each day to “Master” competence and self-respect. These precautions reduce the likelihood of self-harm, and in my experience they also work well for patients struggling with addiction and the triggers that can lead to relapse.

Distress tolerance skills are also known as crisis survival strategies. I most often recommend pleasurable distraction—which can be as simple as reading a book or watching a movie—in consultation-liaison settings where severe medical problems lead to pain, anxiety, and loss. With patients who cut or burn themselves, I often recommend squeezing ice cubes or snapping a rubber band against the skin as an equally painful but harmless alternative.

Interpersonal effectiveness skills are best taught when patients are not inpatients that have work or relationship problems once they get well enough to participate in their discharge plans. They’re also helpful for medical patients who are having trouble getting along with hospital staff.

The Contingency Management Process

Many borderline patients have learned that hurting themselves is the only way they can get help, and DBT is designed to reverse the unwitting reinforcement of “crisis behavior” that can occur in traditional modes of treatment. Through a process called contingency management, DBT therapists examine how patients somehow end up having their adaptive behaviors punished while their maladaptive behaviors get rewarded. Once you identify these dysfunctional patterns, you then use behavioral principles to create a new reinforcement schedule.

For example, instead of receiving an emergent appointment after an episode of cutting, a DBT patient who self-harms will typically be denied access to his or her therapist for 24 hours (someone else fills in, so the patient is never actually abandoned). On the other hand, adaptive behavior—such as applying DBT skills instead of self-harming—is rewarded by the therapist being available for telephone consultation outside of office hours.

In everyday practice, contingency management can be as effective as it is counter-intuitive. In outpatient settings, consider offering walk-in hours or more frequent appointments for borderline patients, ensuring they have access to care before their troubles reach a crisis stage. Try to resist the temptation to hospitalize after every instance of self-harm. On the other hand, in rare cases, some patients may benefit from brief, occasional admissions “whether they need it or not” when faced with ongoing personal crises. Fixed reinforcement schedules like this one translate readily to other inpatient and consultation-liaison settings, where demanding patients can disrupt entire wards. If patients are told the call button is only for emergencies, their behavior can escalate rapidly. But a short visit from a nurse or psych tech every 30 to 60 minutes—during which validation should be offered—is a better approach.

The technique of “validation” occupies a special place in the DBT toolbox. This is because patients who are constantly being pushed to change their self-defeating behaviors may experience this as being “invalidating.” Essentially, they feel that they are being criticized for being ill. To offer validation, I try to step beyond empathic reflection to let patients know their feelings make sense in the context of their own unique experience, even if I don’t agree their behavior is the best way to solve problems. For example, I might say, “I can see how in that situation, it seemed like overdosing was the only way you could get anyone to listen to you.” Validation is effective in a wide range of circumstances, including when borderline patients present in crisis, addicts struggle to maintain sobriety, or medical patients become angry at hospital staff. I even use it when I’m not at work!

DBT adapts well to a multitude of clinical situations. Although not all DBT techniques work for everyone, most psychiatrists and their patients will find something that works for them.

Additional DBT Resources

- For a thorough review of how DBT principles can be applied in general practice, see Dimeff and Koerner, Dialectical Behavior Therapy in Clinical Practice: Applications Across Disorders and Settings, Guilford Press, 2007.

- Behavioral Tech, LLC (www.behavioraltech.com) offers assessment and research tools for clinicians and informational materials for patients.

- DBT Self Help (www.dbtselfhelp.com) is a website with information for patients and families that is written by people who have been through DBT.

KEYWORDS personality disorders psychotherapy

Issue Date: March 1, 2012

Table Of Contents

Recommended

Newsletters

Please see our Terms and Conditions, Privacy Policy, Subscription Agreement, Use of Cookies, and Hardware/Software Requirements to view our website.

© 2025 Carlat Publishing, LLC and Affiliates, All Rights Reserved.

_-The-Breakthrough-Antipsychotic-That-Could-Change-Everything.jpg?1729528747)